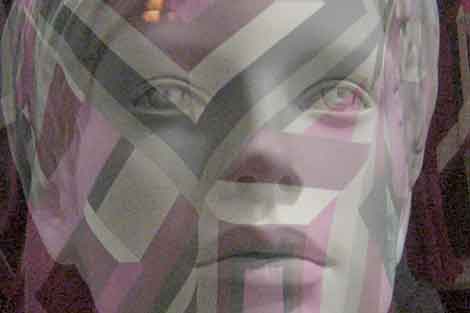

In Scott Stark’s The Realist—fresh off premieres at the Toronto and New York film festivals, and screening later this month as part of a REDCAT nano-retrospective of Stark’s three-plus decades of tenacious experimentalism—a gaga pair of drop-dead gorgeous department-store mannequins wiggle, wriggle and smash their way into life, out of their habitat (an array of window and merchandise-counter displays at an unnamed Austin-area shopping mall), and down through a melodramatic spiral of attraction, engagement, entrapment and betrayal.

Easy for me to say.

Accounting for Stark’s miracle of cinematic quickening, on the other hand—a miracle whose roots are sunk deep into film history, as far down as Sergei Eisenstein and Weird Ed Muggeridge—seems matter sufficient for a monograph. Here it shall suffice to say (based on two weeks’ frantic perusal of everything the filmmaker has seen fit to post on Vimeo) that with The Realist, Stark appears to have crossed a major threshold, pressing a prolific lifetime of homespun memes and special effects, of gestures comic, cosmic and ambiguously political, into the service of a cinematic saga of sorts, a movie-movie for once, augmented by glossy hit-and-run production values, timed to a preexisting music score (American minimalist David Goode’s 1998 large-ensemble piece Tunnel-Funnel), and knit together in ways calculated to mess with viewers’ expectations of narrative coherence.

Enter Ned and Judy, as Stark dubs his protagonists in the press materials—or, as I found myself thinking of them once the engine of eros had kicked in and torn them to pieces, Punch and Judy—a pair of full-body department-store mannequins who, following an intense moment of recognition (as in “Hey, we’re the only ‘people’ around here with heads!”), begin their search for a language in which to share their discovery of each other and their impulsive longing for a way out of their high-end consumerist environment, a way past the dazzling “smooth talk” of fashion and product and packaging design.

The trick to animating these wooden (or polystyrene, as the case may be) figures—and of putting them into more intense communication with each other—lies neither in some demiurgical Word of Life nor as the answer to some latter-day Geppetto’s prayer of petition, but rather in the fx toolbox Stark has put together over 75 short films and counting, in sketchpad work after sketchpad work (at least one of which, “Tracks 1-5,” is also on the bill at REDCAT). For example, having embarked upon a “dialectical” juxtaposition of images, of the kind with which Eisenstein experimented in his “Bolshevik” films of the mid–to late ’20s, Stark loops the splice and accelerates the repetitions, thereby rubbing or smashing images together in hope of igniting Promethean sparks of synthetic understanding. Or again—in what I take to be an original move, or at least an original approach to generating a cubist interpenetration of perspectives—Stark uses the images captured by a stereoptic camera (think Viewmaster) to produce rapidly occillating parallax views of his subject. This three-dimensional “wiggling” effect carries a conviction of urgency at once erotic and dramatic—as in a sequence where the rapid intercutting of brick wall and leaf-scattered lawn (an image for which another short in the REDCAT program, Speechless, provides the interpretive key) feeds into tableaux of dismembered mannequin limbs.

That said, it should promptly be noted that the film’s indefinite sense of forward momentum and episodic structure derives as much from the pull of David Goode’s “process” composition as it does from the progression of mute images. Indeed, The Realist is timed to the precise length of the Goode piece, which seems at times to have grown out of the first two bars of Stardust, which the recent Hoagy Carmichael biography called “a song about a song about love.” Which would make Stark’s film what? “A song about a song about a song about love,” presumably. Which may or may not come as news to Scott Stark.

As to the film’s title, it’s hard to say. Is the evocation of “realism” literary, cinematic? Either way, it’s an ironic appellation indeed when applied to Ned and Judy’s relentlessly artificial habitat. Is it a psychological “realism” born of disillusionment with consumerist and/or boy-meets-girl romantic idealization? Or is it simply a reference to the vintage Stereo Realist camera that Stark used to create the jiggled perspectives that drive his vision? Best, probably, to settle on all—and allow for the possibility that it’s none—of the above.

Or better yet, bring the matter up at the Q&A.

The Real and the Hyper-Real:

Films and Video by Scott Stark

At Redcat, Monday, November 25.

www.redcat.org/event/scott-stark-0