Your cart is currently empty!

Film: Lost and Found

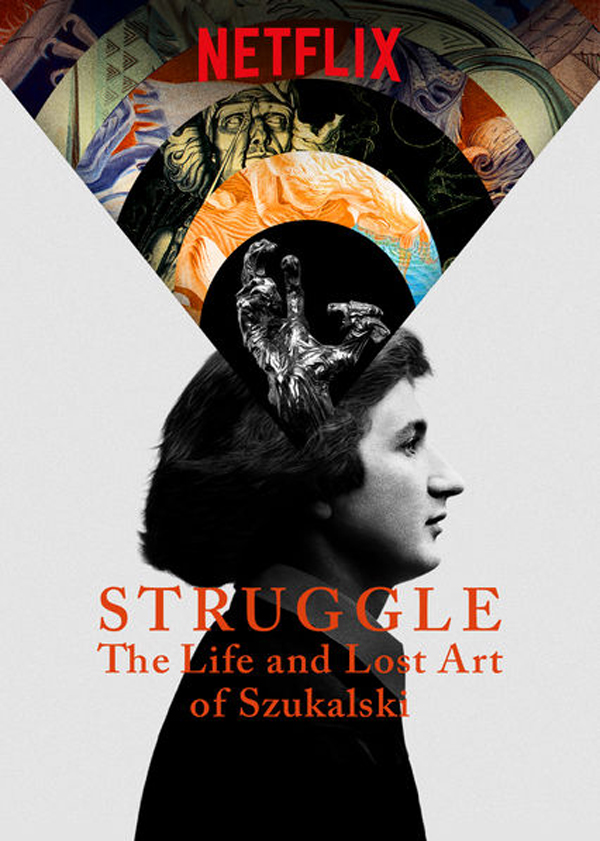

There is a myth, subscribed to by all ambitious but unsuccessful artists, that they will be discovered posthumously, and their work revered by future generations. That may be cold comfort, but when it comes to fame, the SoCal artist Robert Williams doubles down with his bleak but realistic dictum, “If it doesn’t happen to you when you’re alive, it doesn’t happen.” True dat, but maybe it’s even worse for an artist to have been famous in their lifetime, only to see their reputation diminish to obscurity before their death. Such is the case of the European artist Stanisław Szukalski, a man once in line to be heralded as Poland’s greatest artist. Born in 1893, his astonishing rise to fame and descent to anonymity are the subject of the Netflix documentary, Struggle: The Life and Lost Art of Szukalski, a film that revives the career of this iconoclast and self-professed genius.

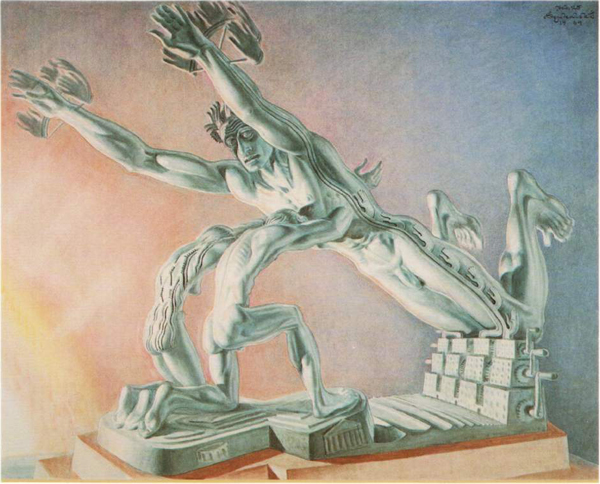

Produced by Leonardo DiCaprio and directed by Ireneusz Dobrowolski, the film opens with the late 1960s discovery and awed appreciation of Szukalski’s work by Los-Angeles–based art collector and cultural archaeologist Glenn Bray. Through a series of coincidences, Bray finally met Szukalski, who had left Poland in 1940 with his wife Joan and was living in the San Fernando Valley. Although essentially penniless and forgotten, Szukalski spoke and acted as though still at the top of his game, and it was this ruthless self-aggrandizement, coupled with his high-caliber talent, that persuaded Bray to introduce the artist to his friends Robert and Suzanne Williams, and to George DiCaprio, Leonardo’s father. These denizens of the ’60s and ’70s Los Angeles underground art scene suddenly found themselves in the presence of a man who at age 13 had attended the Art Institute of Chicago in 1906 and enrolled at Kraków’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1910. Unraveling Szukalski’s past was a formidable task, but Bray discovered that the artist had produced an impressive body of monumental sculptures in his lifetime, and in the late 1930s had even been groomed by the Polish government to become the cultural harbinger of a new Nationalist Art tailored to his specific vision.

But reality has a way of thwarting the best-laid plans, and during the German invasion of Poland in 1939, all of Szukalski’s work was either lost when a bomb directly hit his studio in Warsaw, or destroyed by the occupying troops. Consequently, Szukalski and his wife returned to America with little more than two suitcases and began their life as stateless emigrants. Unable to return to Poland and virtually unknown in America, Szukalski eventually found work sculpting miniature sets for films, but recognition of his prodigious artistic talents eluded him. Without the money to afford a studio, Szukalski turned to graphic work and making small sculptures, all the time creating an alternative theory of human development called Zermatism, something he would enthusiastically expound upon until his death in 1987.

Although Struggle: The Life and Lost Art of Szukalski is a comprehensive and entertaining biography of a man who seems to have suffered greatly for his art, the film also reveals the inconvenient truth that many people suffered greatly for Szukalski’s art. Apparently, shortly before the war, the artist made a Faustian deal that backfired; something that, in one interview, George DiCaprio finds unforgivable. Other people don’t see this as a complete negation of Szukalski’s achievements, preferring instead to place the aesthetic success of his work above his failure as an empathetic human being. Watch the film and decide for yourself, for there is no single answer to the question. What is more important: the art, or the life the artist lived to make it?