Who said being an artist was easy? Today Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is known as the top-selling woman artist in the world, but it’s hard to believe how many difficulties she had to overcome before she got to where she is now. Or perhaps, not so hard to believe, since a woman who aspires to become a “great artist” typically finds barricade after barricade thrown in her path, simply because she is female. The new documentary about her and her work, Kusama—Infinity by Heather Lenz, is a fast-paced and engrossing look at the personal struggles and public career of this remarkable artist.

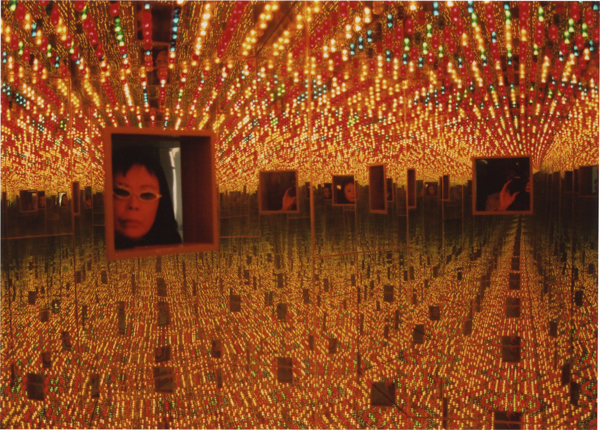

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room-Love Forever, 1966/1994. Installation view, YAYOI KUSAMA, Le Consortium, Dijon, France, 2000. Image © Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy of David Zwirner, NewYork; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London; YAYOI KUSAMA Inc.

Who has not seen her dot-covered objects, her pumpkins (in prints, paintings, sculpture), her immersive roomful installations in person or in reproduction? In Los Angeles we have the chance to stand in one of her Infinity Mirror Rooms at The Broad—for only a minute, but what a minute as we look into pinpoints of lights, stretching into infinity.

Born to a well-to-do family in Matsumoto City in 1929, Kusama began drawing and painting repetitive dot and net motifs at age 10. In interviews she is candid about her hallucinations—at times seeing the world covered in dots or flowers (her father ran a seed company)—and her later diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Artist Yayoi Kusama next to her “Dot Car” (1965) in KUSAMA – INFINITY. Photo credit: © Harrie Verstappen. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Despite being discouraged by her conservative family, she was determined to become a successful artist. In 1958 she moved to New York, and set up a studio—the word gutsy comes to mind. She was soon painting the Net Paintings for which she would become known, as well as making soft sculpture—creating roomful of objects covered or filled with phallic-shaped stuffed cloth. Lenz makes the rather bold assertion that Kusama profoundly influenced the New York art scene—soon after an exhibition of Kusama’s soft sculpture pieces, for example, Claes Oldenburg launched onto his soft sculpture series. Much of the evidence presented is circumstantial, but it does indicate that Kusama was often ahead of the curve, even in an art art world dominated by men.

Eventually, impoverished and rather on the edge, she returned to Japan in 1973, and eventually checked herself into a mental hospital in Tokyo, where she resides today. Fortunately, somewhere along the line, she also established a studio, and became so well known that she was nominated the artist to represent Japan at the 1993 Venice Biennale. Since then she has had major retrospectives at LACMA, the Tate Modern, and the Whitney, and she is now represented by David Zwirner.

While the doc includes comments and interviews with art experts, Kusama herself provides the best insights. The direct interviews with her are riveting. Dramatically dressed in eye-popping outfits, often with a blunt-cut wig, she responds to questions with well-crafted, highly intelligent answers. It’s the way she talks—in a steady stream, without inflection, and gazing straight ahead into a far distance—that’s disconcerting and hints at her mental state. The fact is, art saved her—the repetitious nature of her mark-making has been a way to express and to release the phobias that have plagued her, to help steady her mind and gain a sense of accomplishment. Art also saved her because she has achieved what she set out to achieve, to become a successful and famous artist, and all the financial stability and resources that implies.

Magnolia Pictures will open KUSAMA – INFINITY, filmmaker Heather Lenz’s fascinating portrait of the top-selling female artist in the world, on Friday, September 7 at the Nuart Theatre in West Los Angeles and Film Forum in New York, with a national rollout to follow. On Friday, September 14, the film’s run will expand to include Regency’s South Coast Village 3 in Orange County.