The Los Angeles County Museum of Art continues to set a high bar for film exhibitions with their latest, “Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s.” The striking exhibition design by architects Amy Murphy and Michael Maltzan has it “interrupted” by three tunnels—two showing film clips, one filled with drawings. It’s an experience of going from light to dark, and back again—so very apt for this exploration of German Expressionist film of the early 20th century. That movement featured much dark subject matter (murder, madness, mayhem) amid chiaroscuro lighting, with bold experimentation in set construction, lighting and special effects.

Expressionism, of course, did not begin in cinema but in other art forms such as painting and theater in the early 1900s. It turned its back on realist traditions and sought higher truths—personal, emotional ones. The show’s curator, Britt Salvesen (also LACMA’s curator of photography and prints/drawings), points to “the German Expressionist attention to psychology and their efforts to manifest characters’ inner lives not only through writing and acting, but also through all aspects of production design.” The movement, she says, also “planted the seeds for many of the film genres that continue to thrive today: horror, science fiction, noir.” Some of the classics in this exhibition are The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Street Without Joy, Metropolis, The Blue Angel and M.

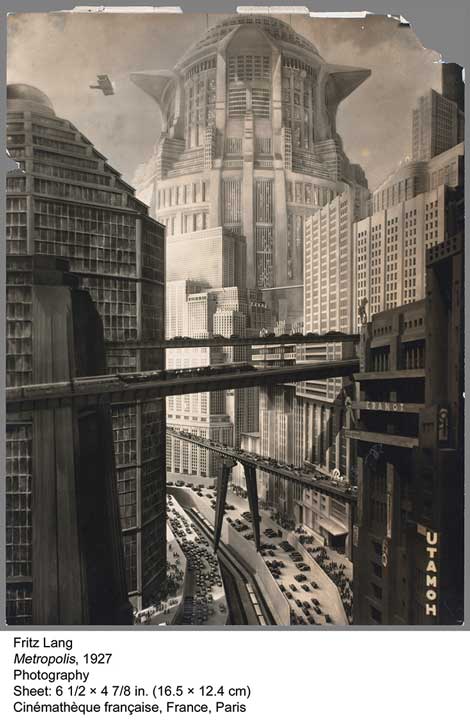

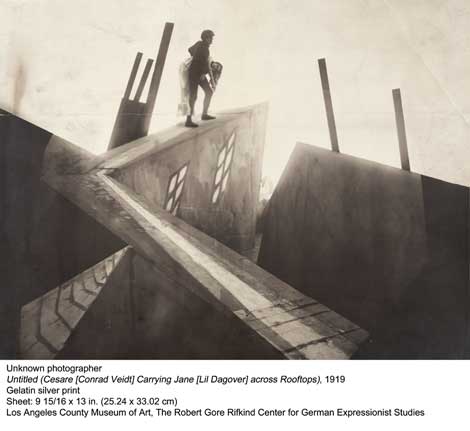

There are some 250 objects in the show, and that includes photography, drawings, posters and a few artifacts including a replica of the famous machine robot from Metropolis—you know, the one you always see in posters for the film. The set drawings are works of art in themselves, not just diagrams or instructions— they are drawn with off-kilter framing, strong shadows and distorted perspectives. The tilted shot, called “Dutch” or “German” in the industry, deliberately created unease and discomfort, and is famously used, over and over again, in the landmark The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), directed by Robert Wiene.

Caligari is an early horror film, perhaps the earliest, about a “doctor” and his hypnotized slave who may be involved in a series of local murders. It reflects a fascination with hypnosis and psychology and the subconscious. Perhaps on a deeper level, it reflects the culture shock in Germany after its World War defeat, Empire’s end and the fall of the Kaiser. Does Dr. Caligari symbolize the omnipotence and oppression of the state over individuals? As German critic Rudolf Kurtz has said, “Expressionism isn’t an artistic genre but the expression of a world crisis.”

For Caligari, designer Hermann Warm and painters Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig created highly theatrical sets, painting highlights and shadows directly onto flat panels—the film is featured in this exhibit with illustrations and clips. Also notable are the set designs of Otto Erdmann for G. W. Pabst’s Street Without Joy—they’re done in watercolor, with a grayish palette bordering on monochromatic—and of Andrei Andrejew for several films.

One section of the exhibition is about the often-overlooked subject of film sound—“silent films” when shown were not actually silent; they were accompanied by live musicians and sometimes even had a specific score. Another section, in the “tunnel” that’s shaped like a ziggurat, is about steps and ladders, and how often they appear in these films. Sometimes they are a grand staircase, such as the one in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) that leads disgruntled workers towards the “Heart Machine” they are intent on destroying, and sometimes they are crude ladders leading to an unknown region outside the frame.

Inspired by the exhibition, I rewatched Metropolis on a Kino DVD. It had always felt a bit disjointed to me before, and the included documentary showed me why—it had been completely re-edited by Paramount to make it shorter and more palatable for American audiences. (When released in Germany in 1927, it was 153 minutes, and proved too long even for German tastes—it was also cut down there.) Nevertheless, the story always came through with remarkable resonance. It’s a tale of the haves with their robust sons enjoying leisurely sports in an Edenic garden and riding around in limos, versus the have-nots, the ashen workers, who toil long hard hours and retire to grim underground lodgings at night. The crowd scenes with their early special effects still have great energy.

Curator Salvesen understands the right balance among still pictures, moving ones and text. She has created a show of such density and delight that you will certainly want to see it more than once. The exhibition was adapted from the one at the Cinémathèque Francaise in Paris in 2006. Additional objects have been added from LA-based collections, including those of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and LACMA itself.