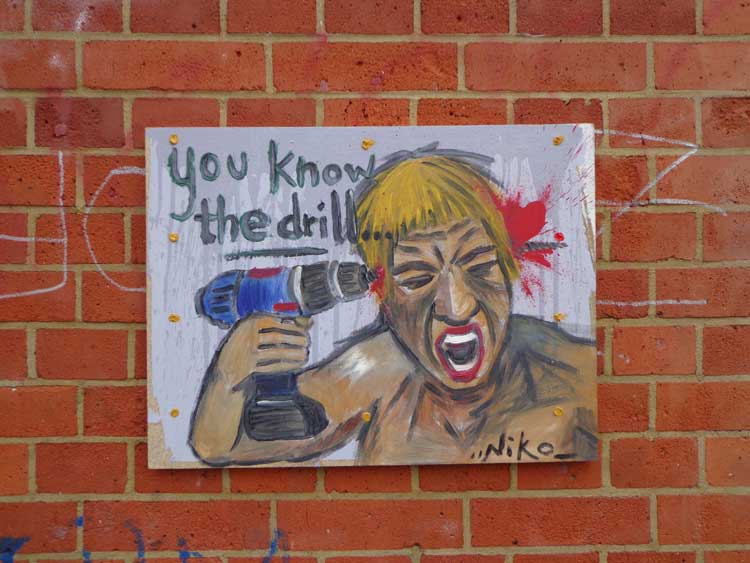

Painted on a small particle board, screwed to a brick wall, above and behind which Berlin’s U-Bahn (here elevated) rumbles to and from its terminus, a figure of indeterminate sex holds a power drill to its head, the bit twirling out the opposite temple in a splash of red pigment. The agape mouth conveys a scream of pain—and perhaps a dollop of pleasure. In the upper left, the words, “You know the drill…” Funny. Now, who’s going around the city screwing paintings into walls?

The artist’s signature—Niko—gives little clue, as with the figure, to even the gender. Patience, perseverance and some deft keystrokes into Google Images eventually lead me to a facebook page (Niko Color, an alias) and from there, to contact with the artist himself. Besides being a “him” rather than “her,” Niko (who doesn’t want his real last name revealed) turns out to be in his late 30s, and a relic of the Berlin art scene in an earlier, more earnest incarnation—before the gallery gold rush in the now-branded “Creative City” led even so-called street artists to boast representation and reputations. “I don’t sell these paintings because it is part of my art to put them in the streets,” he tells me. “I’m not interested in making money and the paintings without the street would only be a half-work.”

He toils in a cluttered living room “studio” in a down-at-heel immigrant hood, still a brisk bike ride away from the nearest trendy-colored anything. There are rectangular panels salvaged from cheap furniture and whatnot stacked in the foyer. “I used to try painting on canvas but it’s too expensive,” he explains. “In my neighborhood, they throw out so much junk, that I take all these boards home and paint on them.”

His explications are couched in the language of simple, logical problem-solving rather than the turgid academic meanderings that characterize the typical artist’s statement or grant application. “Then I am looking at these paintings and wondering, ‘Okay, hmm, now they are finished, how will I show them?’”

“You know the drill… ” is then both the title of the work I first discovered and a statement of Niko’s artistic process—though he does not go out in public with anything as attention-attracting as a power tool. Rather, he roams the street looking for holes that are already there. Thus it is not he who ultimately chooses where a portrait of a German hip-hop wannabe can hang, or where to put “Angelus Dwarf,” his interpretation of Jean-Francois Millet’s The Angelus, wherein the farmer couple are replaced with a pair of German garden gnomes. His “exhibition” spaces are at the mercy of Berlin and its unfilled holes. As a result, a Niko (oil on sort-of-wood, not Krylon on brick) pops out at unexpected heights and angles on your way to and from your job, the store or your preferred inebriation venue—from overpasses, beside doorways and on random walls throughout the city.

Once discovered, most pre-bored surfaces require some quick measurements and notes before he returns to his studio-cum-flat to drill the proper array of holes (all German efficiencies implemented here). If the hole pattern is not perfectly square or rectangular, he applies a paper overlay through which holes are punched so the sheet can be used to create the identical pattern back at his “studio.” His “kit” therefore includes a tape measure, some screws and dowels of various sizes. The latter he inserts into a set of asymmetrical holes we discover before he punches through the paper. “There’s no flexibility with wood,” he says. “You have to get the holes just right.” Once that’s all done, he can return and quickly mount the work in the stealth of broad daylight, camouflaged in the kind of bland work jacket usually worn by generic company arbeiters.

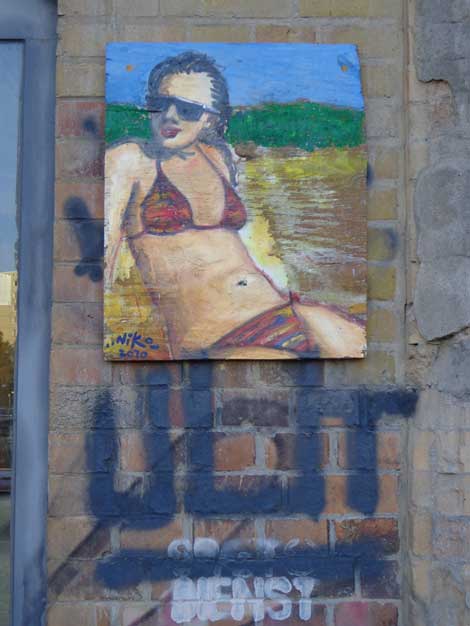

Through these and other stratagems (though he dare not divulge those, as it makes the works easier to steal), he’s hung over 165 public pieces since he began in 2004. Some last a few hours or days before being removed. Others receive comments in kind, such as a bikini-clad figure on a fashionable Mitte street that had the word “Jut” (Berlin slang for Gut or “good”) spray-painted underneath it, with only a slight bleed-over into the work. “It looks like they respected my work and tried not to paint on it,” he says. “They could have tagged all over it. Lots of people do.” Some manage to remain unmolested for weeks and even years, though the savage winters take their toll.

Park perimeters are particularly hospitable to Niko, as they all have metal sign structures that usually have more holes than messages the city can put up announcing what’s verboten. Niko takes me to one in a chic Mitte neighborhood. The bottom panel on the sign shows the ample backsides of a pair of municipal code enforcers known as the Ordungsamt, casting their eyes afield, above which is scrawled the cliché German query (and the painting’s title): “Alles in Ordnung?” (“Is everything in order?”).

The answer, as is often the case, depends on the viewer’s perspective.

All images by Niko, photos by Mark Ehrman