William J. Simmons, art historian and Special Projects curator of the Felix L.A. art fair.

EMILY WELLS: Your curatorial practice seems to be steeped in your background in queer and feminist art history. How do you see these two as informing each other?

WILLIAM J. SIMMONS: It is an oft-forgotten fact that feminist and anti-racist activism informed, enabled even, queerness and queer art history. Identity movements build upon each other. Queerness does not replace feminism, for instance. In some ways, feminism and anti-colonial theory opened our eyes to difference, and queerness has offered increasingly vast ways of discussing difference. One cannot exist without the other.

My most important professors at Harvard were women who might be labeled “second-wave.” So too are some of my favorite artists, like Judy Chicago, who has been a friend and mentor for nearly a decade now. I am so grateful to have had those feminist experiences, in some ways “before” I came to queer theory. I want to approach a cumulative art history as well, one that takes into account the conflicting attachments that writers, artists and curators may have simultaneously.

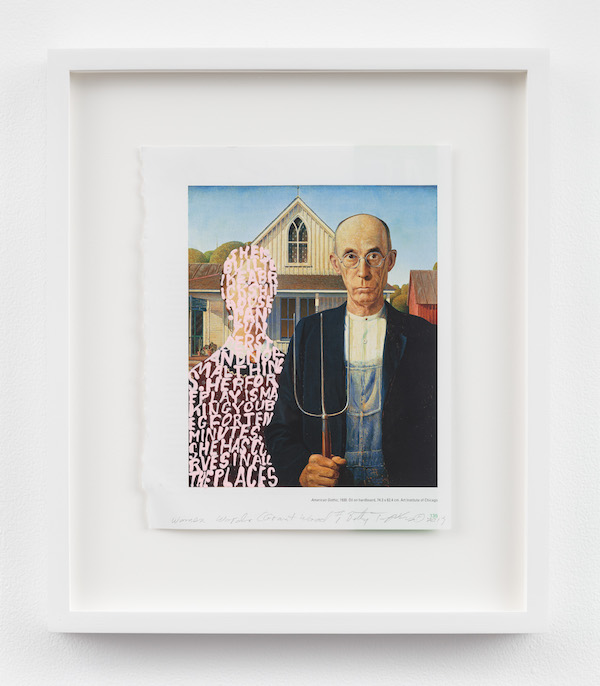

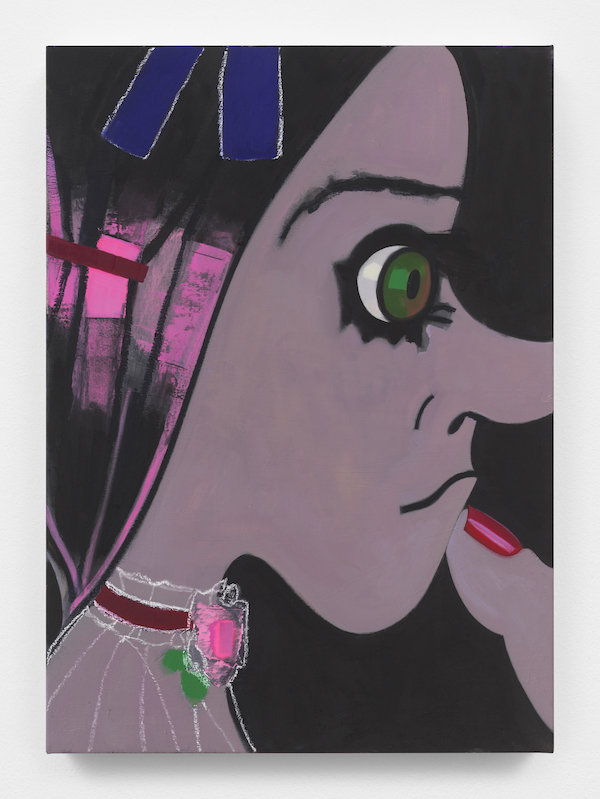

Ellen Berkenblit, Rosemary Strawberry, 2019

You’re featuring artists that you’ve championed for a long time: Judy Chicago, Betty Tompkins, Martha Wilson, Eve Fowler, Math Bass and more. In putting the project together, did you find yourself relating to their work differently than you had before?

Well, I wish I had a more profound answer, but I would say it was definitely interesting seeing all of their work from a business point of view. It’s an experience that everyone who deals in “objectivity” should have. We ought to have much more respect for gallery professionals—shoutout to folks like Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, Sascha Feldman, Maggie Clinton and Kristen Becker, who empowered me more than any professor. Anyway, this process was a reminder that there is no such thing as objectivity. Art historians are not objective. Critics are certainly not objective. I think that’s great. We should all be unabashedly supporting our friends. We should be helping queer, female-identified and POC artists make money and get famous and get verified on Instagram.

Mathieu Malouf at Felix LA.

The Special Projects series this year is focused on gender, queerness, and feminism, and the art you’ve selected grapples with the possibilities and limits of art-making on these fronts. How do you see the show as grappling with that enigmatic confluence?

I think all of these artists work through those concepts in very capacious ways, which is why it was so interesting bringing them together. For instance, I think of Paula Hayes and David Benjamin Sherry as eco-feminists and/or eco-queers. How often do we forget to consider the natural world and spirituality in our queernesses or feminisms? Likewise, Deborah Kass’ work has always operated in those interspaces because of her interest in pop culture, which is an area wherein we can discuss gender, sexuality and race, certainly, but we can also discuss slipperier terms like attachment and aspiration.

Amoako Boafo at Felix LA.

And I also think that each of these artists is both loving and critical of their chosen media. For instance, I think that Anne Collier’s work has been associated with feminism in a simplified way. I’m not mad about that and I don’t think it’s wrong, but I wonder what kinds of feminisms emerge when we focus not so squarely on deconstruction and critique as markers of “good” feminism, but rather on feminist attachments, feminist hopes, and disappointments, or feminist loves that are paradoxical or unexpected.

Audie Ramirez at Felix LA.

I really love your curatorial text to accompany the Special Projects series, focusing on “cruel optimism,” which theorist Lauren Berlant says “exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” How does your relationship with language inform these vivid visual experiences?

I’m so glad that you asked this question. I tell my undergrads to read Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, which is sort of an ur-text in art history, like it is a poem. I never tell the faculty that I do this, because what they want is for the students to understand it, to “get” it, to map out the studium and punctum. That’s wrong. Academia always gets it wrong. Much of Barthes’ work is about being sad and queer and horny. In the case of Camera Lucida, he uses images and visuality alongside those feelings, not necessarily as illustrations of those feelings. Julia Kristeva, another philosopher whose work I think art history has wildly misread, does the same. This is what I want to do as well—to use language and vision in proximity to each other and to never reduce one to the other. Whether this is actually doable in a curatorial capacity remains to be seen. I hope people read the text and wonder if it has any relationship to the work I selected at all. I also hope that Lauren Berlant will read it and not be entirely repulsed that her words are being used in the context of an art fair.

You wrote, “We expect so much of art, of representation, and yet it cannot ever fully articulate the dreams we have for ourselves and society, creating thereby a state of endless oscillation between hope and despair,” which was apt, as I’m trying to finish a book chapter on the limits of representing the experience of invisible illness. As our culture increasingly grapples with demands of representation, how do you see the conversation about what can/can’t be represented playing out?

I can’t wait to read your text. I’ve always admired how you talk about illness and the body and movement. Illness is a fascinating context. I’m working on something about Félix González-Torres. In his work, illness is often read into it, as is the case with most artists associated with “AIDS art” – Jimmy DeSana, Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, etc. González-Torres’s work is often discussed in terms of “infecting the canon” or even infecting our bodies, as with the candy sculptures. But this is a paranoid reading and not a reparative one. Such readings are steeped in negative affects. How can we get past those without forsaking radicality?

I think we are definitely in an anti-representational space in certain ways, and that concerns me. I’m glad that we are past the years of Ryan McGinley photographing cute white boys being passable queer art. Don’t get me wrong – that’s still going on with this new crop of white, gay painters who paint their boyfriends and Grindr dates. But I think the language now centers more forcefully on abstraction, and that anything abstract is inherently “queer” or “between binaries” or “radical” or what have you. That’s not the answer either. But everyone can do whatever they want. I think everyone has good intentions. And cancel culture is just fine with me. Some things just cannot be “represented” by certain people. Just don’t cancel me!

What are the benefits to a smaller, ancillary fair like Felix? / Did you get to take any risks you might not have at a larger fair?

I don’t know! Because I didn’t actually go to Felix last year! So it remains to be seen.