Injecting one or more inane Star Wars puns into a discussion of George Lucas’ proposed museum would be de rigueur; but I’ll abstain. It is time to take Lucas’ idea seriously. Suspend the adulation. Cut the skepticism of commercial pictures’ merit. A 275,000 square-foot museum with Lucas’ $400 million endowment in Exposition Park is not to be taken lightly. Let’s contrast what this embryonic institution is with what it purports to become.

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art “is a museum without boundaries,” proclaims its slick homepage. Now, that is obvious. The un-built museum doesn’t yet comprise a structure—or even a collection.

Then, what does it comprise? Words. A name and explanations, also indefinite, out-of-bounds. A lucasmuseum.org section titled “What is Narrative Art?” answers, “Narrative Art is visual art that tells a story.” But the notion of narration as a single defining characteristic is so generic that it fails to differentiate narrative art from any other type of art. After all, the trite adage that “A picture is worth a thousand words” exists because most images, whether representational or abstract, either betoken or evoke some kind of story.

Underneath the self-referential definition, several platitudinous explanatory paragraphs scarcely elaborate the initial sentence. Never mind; artworks, not words, make a museum. Let’s inspect the museum’s proposed content.

Here, we encounter major obstacles.

Some have reported that the museum will contain the 40,000 objects—10,000 paintings and works on paper and 30,000 film mementos—all from Lucas’ own collection. But a recent story in the SF Chronicle implies that the “Lucas Seed Collection” will contain only about 700 items, though “the museum will eventually have its pick of the rest of the collection.”

When I contacted museum officials to request an enumeration, however, spokesman David Perry replied, “There is not yet a list of the seed collection,” and re-directed me to lucasmuseum.org.

The website itself offers no firm figures: “The Museum’s collection, launched with inspired objects from George Lucas’s personal holdings, is growing to encompass an unparalleled presentation of narrative art forms,” it says in one section. In another: “Mr. Lucas’ collection provides the seed from which the Museum’s collection will grow for decades to come. From that foundation, the curators of the Museum will build a collection.” What sort of pick, in what quantities, and when, remains unknown.

The website did elaborate on its curatorial outlook, but failed to provide much illumination. One section, titled “The Collection” declares: “The Museum’s holdings, while an actively expanding collection, looks at art through three lenses.” These are: Narrative Art, The Art of Cinema, and Digital Art. How and if the latter two fit under the umbrella of Narrative Art, and why they are separate categories rather than sub-categories, is undefined, as is the relationship between the three “lenses.” Since Narrative Art occupies the museum’s name, it seems most important.

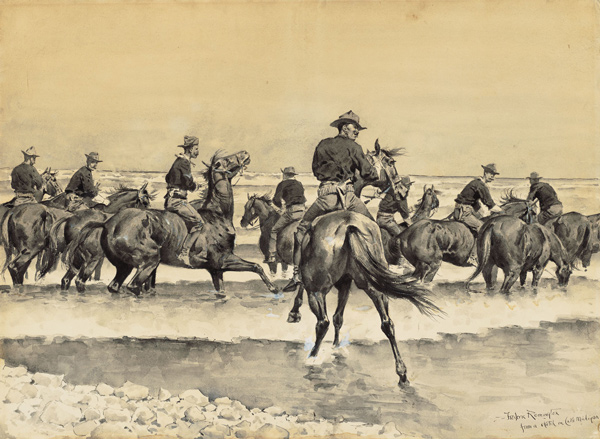

Frederic Remington (1861–1909), Watering the Texas Horses of the Third Cavalry in Lake Michigan, c. 1894

“View Narrative Art,” a subsection of “The Collection,” yields several more subsections. One, “The History of Narrative Art,” shows an impressive array of paintings by artists including Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Thomas Hart Benton and Degas. However, “Some of the featured artwork is not a part of the Lucas seed collection and is here to illustrate the history of narrative art.”

Which examples are constituent? It is unclear. Since we don’t know what the collection includes, how it will develop, or what will complement it, notwithstanding the nebulousness of “narrative art,” we can only guess based on the website.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934), Garden Walk, c. 1905

It provides plenty of examples, and though spurious, they tell a story. Nearly every piece under “Featured Categories” of “Narrative Art” in “The Collection” involves figures, mostly human. People and actions are idealized; beauty and heroism accentuated in scenes laden with nostalgia, fantasy and romance. Negativity is absent or glossed over as in Frederic Remington’s war scenes.

Through this selection, the website paints a picture of what the museum promotes and what it eschews. For instance, Artemesia Gentileschi’s figure paintings, though stylized and realistic, would not fit here for their gruesomeness and age. Neither would Edward Hopper’s, for being too morose.

Charles Edward Chambers (1883-1941) Pampered Treatment

The museum’s inclinations as illustrated by the work on the website and news reports elucidate a fundamental problem. Narrative Art is broad enough to include almost anything. Yet the selection shown on the website is stereotypically narrow, mostly composed of late 19th- to mid-20th century American kitsch, mass media and mainstream commercial art. Furthermore, evidence of ethnic diversity is scant. Most figures depicted on the website are Caucasian. Most included artists are white men.

Lucas’ wife, Mellody Hobson, has vocally expressed a desire for the museum to benefit a diverse array of visitors from “every walk of life.” “Our special narrative is accessibility,” she told the LA Times. “We want to make sure that a black kid from South Central is as comfortable in our museum as an art history student who went to Yale or Princeton.” How will the museum achieve this noble ideal? Given its decision to ignore established art historical narratives, it seems unlikely to attract art history students. What will it offer minority children? The implication seems to be that by showing mainstream popular art, it will automatically appeal to black kids. Would that be simply because the art is popular? Isn’t it condescending to assume that a kid from South Los Angeles couldn’t appreciate less commercial, more intellectual contemporary art were it made accessible to him?

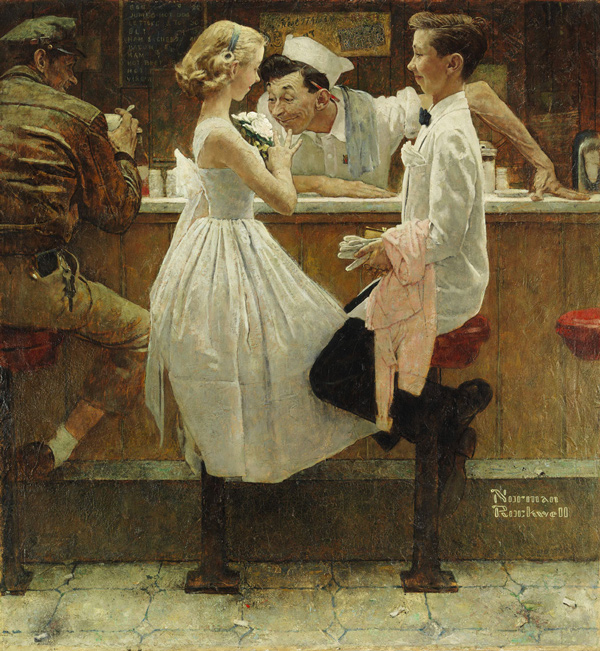

One reason why a person of any age wouldn’t feel comfortable in a museum is that his race is hardly represented. A black kid, or any contemporary kid for that matter, might better relate to Kehinde Wiley or Kerry James Marshall, for instance, than Norman Rockwell. Khalif Kelly’s paintings communicate more about black lives and modern American times than those of Maxfield Parrish. Since Lucas collects mass-media art, how about George Condo’s Kanye West album covers? Well, maybe those would be too provocative; if movie ratings applied to art, Lucas’ taste appears G.

Continuing its narration, the website proclaims, “What distinguishes Narrative Art from other genres is its ability to narrate a story across diverse cultures, preserving it for future generations.” Yet most works are by American or European artists, dating back no more than a couple of centuries. Where are Japanese byobus, Pre-Columbian totems, African tribal sculptures, or Persian miniatures in “The History of Narrative Art”?

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) After the Prom, c. 1957

Their absence is revelatory. Bombast belies an ethnocentric, egocentric institutional narrative reflecting Lucas’ predilections. There’s nothing wrong with a museum built around one man’s taste, but under what authority does Lucas define “Narrative Art”?

Actually, the name is relatively new. Lucas has wanted a museum for years. It was initially to be “The Lucas Cultural Arts Museum.” By all appearances, the “Narrative Art” category was incorporated in a bid to catapult popular art forms like illustration, comics, and mainstream movies into a more elite realm like that of fine art, thus inflating the museum’s status. These popular art forms are perfectly respectable; but for Lucas, respectable popularity is apparently no longer enough. The filmmaker, having achieved financial success and renown, now wants elite validation.

In fact, the reason he devised a contest pitting cities against one another was because he was intent on securing expensive, exclusive public land for free in a prestigious city. Lucas has committed to investing $1 billion in the museum, and covering all construction costs. Why would any city refuse the gift of a museum? Perhaps because strings are attached. Lucas wouldn’t settle for anything less than lakefront in Chicago (at a $10 yearly lease), or national park land in San Francisco. His obstreperous behavior in various locales is well chronicled. Politicians persuaded him to choose Los Angeles, offering him the land for a nominal $20 a year.

The only two photos in the website’s “Media Room” are concept designs of the bizarre structure conceived by Ma Yansong. It’s difficult to determine whether this eccentric building will look more like an avant-garde sci-fi fantasy or a Space Age relic. Either way, it will certainly be conspicuous.

Maxfield Parrish,(1870-1966), Garden of Allah, c. 1918

That so little is known about Lucas’ plans save the museum’s palatial size, improbable architecture, and prime location, speaks of desire for immortality above all. His wavering among different cities rather than selecting a community that he cares about further manifests thirst for self-glorification.

Mass appeal can be an invincible mask for elitist ambitions, as magistrates and executives have long known; and the art world is ripe with opportunity. Unfortunately, by swathing his intentions in equivocal tales, Lucas is leading the impressionable to believe in the Emperor’s New Clothes and depriving his fans of the chance to clearly trace his inspirational roots.

Lucas has outspokenly expressed disdain for art museums’ snobbishness and contemporary art’s opaqueness. “The Lucas Museum will be a barrier free museum where artificial divisions between ‘high’ art and ‘popular’ art are absent,” the website affirms. But without barriers, there would be no museums. We’ve established that Lucas places some art and some artists above others, despite pretensions to the contrary. Lamentably, negative characteristics associated with art museums—hypocrisy, affectation of diversity, overt bias, pretensions of broadness, general pretentiousness, presumptuousness, obtuseness—are magnified here to caricatural proportions.

As it stands—or doesn’t—this museum is a myth. We know virtually nothing about it beyond its self-promoting fables. Maybe its name will be changed again, maybe its location, maybe it won’t even end up in LA. Sadly, at this time, all the excitement about it is blind faith in a fairy tale, not so different than believing that Star Wars is real.

0 Comments