Shulamit Nazarian is pleased to present Sensory Homunculus, an exhibition of new paintings by New York-based artist Bridget Mullen. This will be the artist’s second solo exhibition with the gallery, on view from January 7 through February 10, 2023.

Known for paintings that combine decisive mark-making with experimentation, Mullen’s intuitive practice conjures psychedelic compositions that oscillate between abstraction and figuration.

For Sensory Homunculus, the artist introduces a dialogue on the “problem” of painting, the evergreen discourse on the role of interpretation in art, inviting writer Lara Mimosa Montes as her respondent. Addressing the statement to her peer, Mullen’s dialogue serves as an invitation to consider painting’s ambivalent potential—those distances between painting and artist, observer, body, world—as the space for reflection.

DIALOGUE BETWEEN BRIDGET MULLEN AND LARA MIMOSA MONTES

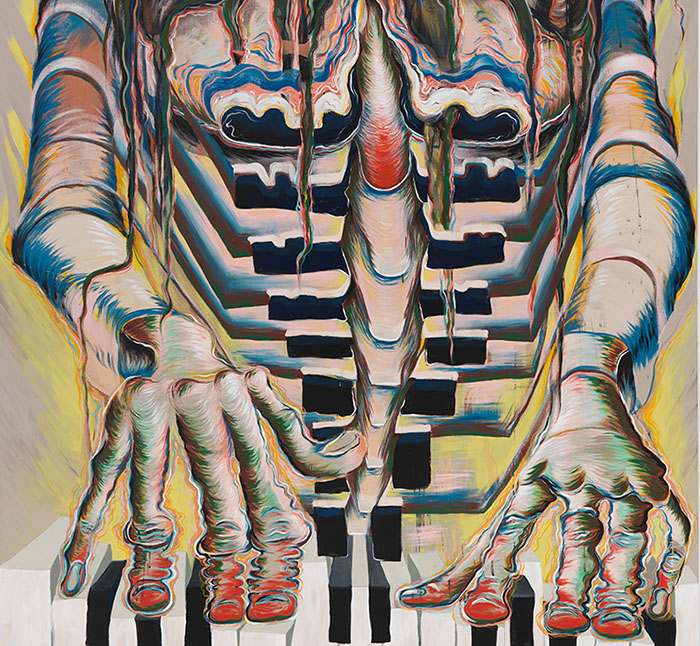

In these paintings there might be anxious, ecstatic, exasperated, snarky, gnarly eyes; eyes at a tipping point, eyes half open but only looking in. There might be big shoulders like football players’ pads beefing up a body or shielding a face. Bird’s eye, mind’s eye, face-to-face, head-on, out-of-body point-of-view. Some shapes have properties that make them seem nameable, and some shapes are nameable but just there for their properties. A painting could be like a body map with parts distorted in proportion to the pitch of feeling held at that part of the body. Unnaturally long arms, monstrous hands, bulging eyes. A sensory homunculus.

Paintings start with wild lines, layered plaids, or abstract shapes, then I repurpose those abstractions, or the spaces between the abstractions, as figures. A few of these works began with a desire to articulate a somatic feeling so loud and persistent that painting body parts inside out seemed the only response. The goal is to run feelings through the obstacle course of my process and use the transmutative abilities of painting to reflect back an invention that resonates.

A painting feels like a frontier. It’s not everything beyond you, it’s the specific space between you and something or someone else—an adaptive, hopeful space. It’s like what’s between thought and when language erupts, or when contact or feeling makes blood bolt to your skin’s surface, blushing, language adjacent, unspoken.

Language shouldn’t solve the “problem” of a painting. What’s the problem?

— Bridget Mullen

THE PROBLEM

I am stretched. I am pressed. I am deranged. I am distorted. I am flesh overgrown, the sentient viscera behind the wall. And I am wavy, hypnagogic. You paint the eyes of a person who is experiencing a moment. Some phenomena transpire and to these we may ascribe some language: Mauve. Clam. Dog. Mollusk. In experiencing the work, I risk my gaze in order to better see myself, but in the act of looking, I also glimpse the other, you. To be with the work, I have to be an emotional chameleon of sorts, capable of changing my mood and open to the movement of a rippling force. I experiment with some mirror play by touching my own face in an attempt to reconcile my self image with my true shape. I imagine you paint an experience of how your paintings experience you, and what you receive from the work without always having a way to describe in words what was given first. In the encounter, the painting, something is rendered, given shape, bestowed form. Whose eyes are wet with gratitude—those of the artist or the canvas? This indeterminate space between the self and the work, what you refer to elsewhere as an “edge-less mess,” reminds me of the day we drove through the mountains with the sea on one side of us and the cliffs all around. We live with an inability to see what lies past the curves, beyond the edge, in us, after us, and inside the forms. It’s also not possible to predict the afterlives of those who will outlive us, people or paintings. But there remains a sense that in manifesting the work, the painting or the poem, we must have dreamed a feeling, or an idea without any real idea of where that feeling would lead. To be in the moment and in the painting with that struggle is to hold fast to belief—trust. In such an instance, one may end up drifting further away from oneself or closer to someone else. This struggle is the joust, a contretemps. What is left in its wake may resemble an unfamiliar figure, some wayward, weird smear of what used to be a person. A sensory homunculus—a wet dredge of frenzy and desire.

— Lara Mimosa Montes