Reception: Saturday September 9, 6-9PM

One casualty of the development of contemporary art since the readymade has been the relevance of formal resemblance as a legitimate criterion for the categorization and periodization of works. In part, this trend is attributable to the expansion of conventions as to what properly constitutes an art medium. Another cause is the assertion that arises from Conceptual Art, that formal criteria are not necessarily aesthetic constitutors at all. Instead, the idea, the concept, the art proposition—these are the relevant determinants of an art work whether or not they are realized in a formal embodiment. Gradually, this notion imposed itself beyond text as index of the dematerialized art object, by insinuating a rupture between whatever formally discernible features a work may have and a referent.

The project of Formalism to divorce style or any formal aspect from historical and social context may be read as a reaction against a nineteenth century scientific bias that would have formal resemblance classify our vision of art much as Linnaean biological taxonomy continues to classify the natural world.

Most often, the imputation of formal resemblance to a figurative referent remains an involuntary response to painting—historically, the medium par excellence of illusionistic representation. Paradoxically, this impulse seems undiminished in paintings devoid of figuration, which we see not as resembling recognizable figurative referents, but other abstract paintings.

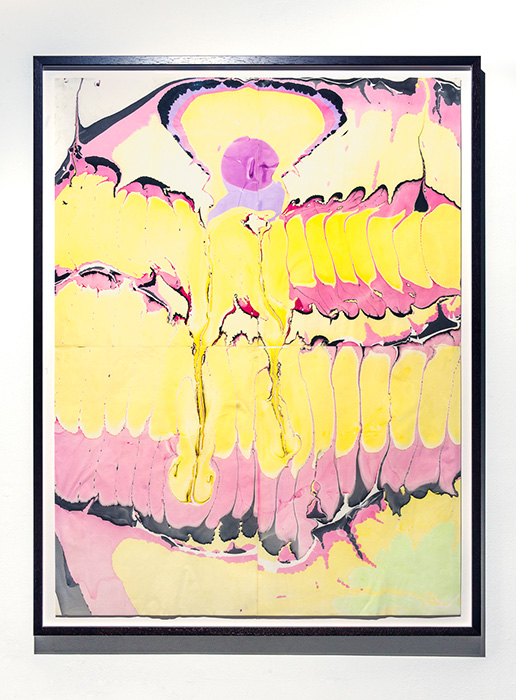

With subtle humor, Rabinowitz’s paintings make a lie of formal resemblance. At first, we are certain that they must refer to something we vaguely recognize. And the artist draws us into this temptation with titles that seem to confirm a figurative association. After all, the works seem to respect general formal characteristics we associate with the natural order. We are certain that there can be no doubt as to their vertical orientation because they reveal a bilateral symmetry that we might come to question upon sustained viewing—they are not so symmetrical as we first might suspect.

Similarly, almost without exception, in the traditional point of visual emphasis in the composition, above center, we invariably find a vaguely round or oval outline where the head would be, were the painting a portrait, or where we might find, for example, the head of an insect in a photomicrograph. But despite our conditioned response to perceive a head at this place in the composition—if we can find any certainty that the artist’s method renders possible a deliberate composition—do these forms resemble heads, and if so, are they the heads of anything to be found in nature, or, for that matter, of any fantasy derived from a natural paradigm that recognition presupposes?

If these images have a figurative referent in nature, then is it macroscopic, microscopic, or simply true to scale? In either case, do we perceive an exterior surface, and if so, a surface that is dimensional or flat? Or is it that we perceive the interior of an organic form, and if so, is the interior dimensional or a flat section rather like that of a CT scan, or an MRI?

When it comes to the illumination of the image, are we to imagine that the light is before the object, behind it, both? If so, should we imagine that the object is opaque? Transparent? Semi-opaque? Is the object in any sense reflective? Is its slightly faded appearance the result of the interaction of light with the medium, or with the object that the medium faithfully depicts? The latter not only provokes further questions with respect to the works’ temporality, it evokes the rather ominous suggestion that the works’ complex of ambiguities of form has begun to infiltrate the surroundings.

In effect, despite that the works become our accomplice in our impulse to ascribe to them a figurative referent, every such referent the works tempt us to imagine potentially is contradicted by other mutually exclusive alternatives that are no less hypothetically possible, and which compound each other in a complex of shifting tensions.

The exhibition title’s most overt association is with a Led Zeppelin album that is not from a single period or narrative, but a greatest hits compilation drawn from nine albums. In Rabinowitz, the mothership is the painting from which all smaller space crafts of formal resemblance launch themselves only to disappear from view as they circulate behind the ship until, when they emerge once more into view, we can no longer tell which of them we are seeing.

—Drew Hammond

Adam Rabinowitz (b.1973, Hadera, Israel) took his BFA at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. A partial list of his solo exhibitons comprises Forde (Geneva), 2009; Tardemon, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2006; and Eshet, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, 2000. Among his many group exhibitions are Real Time: Art in Israel 1998-2008, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2008; The Line of Time and the Plane of Now, Harris-Lieberman Gallery, New York, 2007; Transfer 6, Kunstmuseum Bonn; Haus Lange/Haus Esters Museum, Krefeld; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and the Herzliya Museum of Art, 2002.