There is a moment in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass when the Unicorn says to Alice: “Well, now that we have seen each other…if you’ll believe in me, I’ll believe in you.”

The private question of whether one sees themselves reflected in the art that is available to us is a nuanced one, particularly for Black viewers. It is often conflated with the more macro concept of “representation,” which has become a tedious buzzword and reductive way of gesturing at the historic centering of whiteness and Westerness in painting, which has traditionally left little to no room for the expansiveness of other cultures and their artistic legacies.

It is haunting to imagine how, on some level, we cease to exist if we don’t bargain with others to be seen and believed, which is why the paintings in “Reflections,” Esiri Erheriene-Essi’s first solo exhibition with Night Gallery on view through August, feel like honest (albeit somewhat exaggerated) documents of familiar human experiences: celebrating birthdays, playing card games, gathering with family. If we are to think of art as an archive of truth, Erheriene-Essi’s paintings effectively make the reality of Black life more legible and more alive for those whose default is to look beyond, over, and around the culture.

What I like about Erheriene-Essi’s paintings, which are medium-sized but made larger by the boldness of her animated brush strokes, is that whiteness is the accent sitting at the margins of her figures and shapes, asking to be brought more deeply into the story of the canvas, but ultimately used with moderation as a tool for contrast. By approaching her compositions this way, she subtly illustrates the richness of the color where it appears in the composition, and deemphasizes its absence elsewhere.

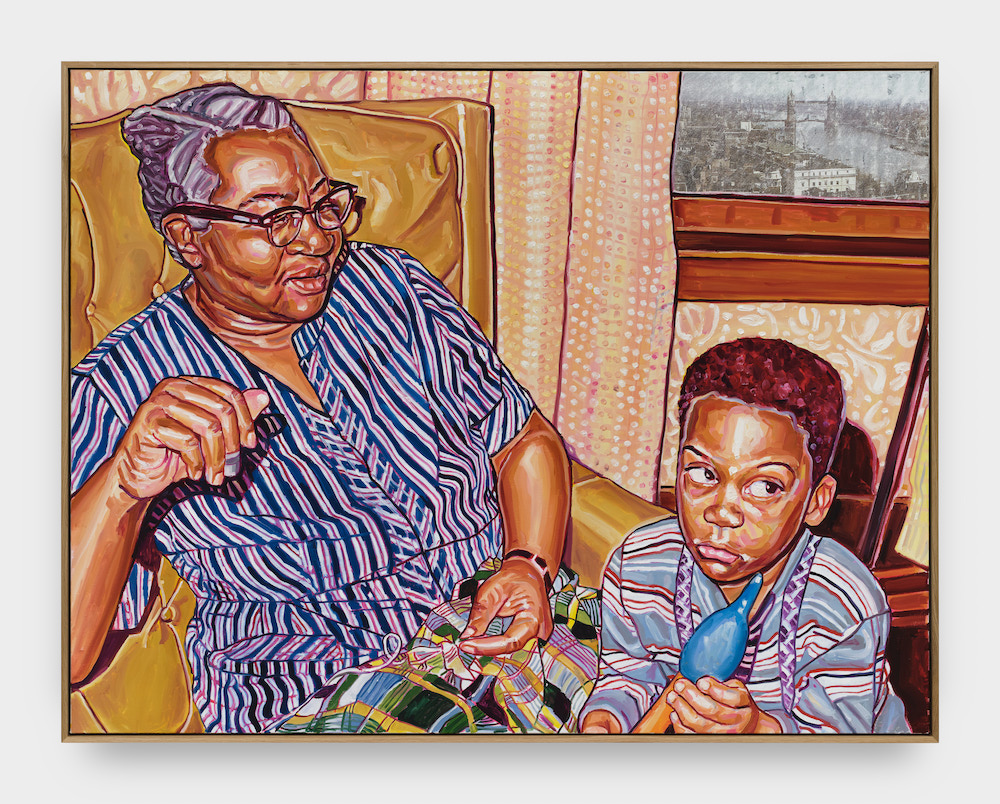

Esiri Erheriene-Essi, Grandma’s Hands, 2025.

The United Kingdom-born and Amsterdam-based Nigerian artist employs blue, pink, and purple tones to give dynamism to brown complexions and textured hair. Though this tactic is out of step with realism, the accuracy of her scenes—which are modeled after real people and vignettes she draws from forgotten vintage family photographs collected from estate sales and online repositories—feel undeniably true.

However, the curious thing about memory—a theme that guides “Reflections”—is that it actually complicates truth; how can we trust that what we remember is as things truly were? I get the sense that though Erheriene-Essi’s figures are seen gathered in groups, they are all individuals with their own version of events. Each one is imbued with so much personality and is granted their own particular posture; it is this attention to individuality that establishes Erheriene-Essi as an artist who refuses to slip into the dangerous default of depicting Blackness as a monolith. More accurately, and as is evidenced in these works, communal Blackness is a diverse microclimate of different weathers.

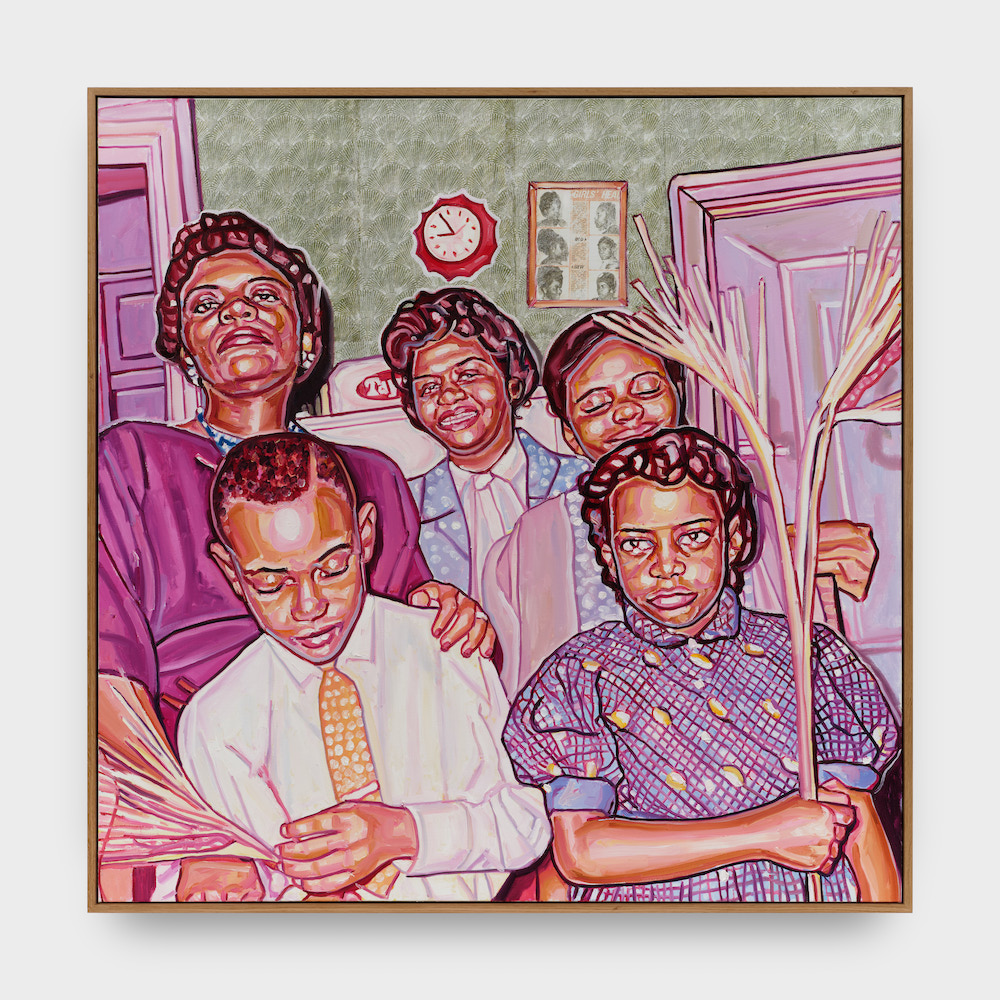

It is impossible to not acknowledge the people Erheriene-Essi paints; the eye contact of her figures in pieces like The Reunion (2024) feels almost intrusive, like an insistence on being greeted. Why are you looking directly at me? I want to ask the family of faces staring back with a Plutonic intensity. As viewers, we are given permission to look at them, and they return the gaze as if to say, “Well, now that we have seen each other…”

Esiri Erheriene-Essi, As my grandma always used to say, don’t go borrowing trouble, 2023.

Perhaps I’m too avoidant, and the intimacy of eye contact makes me feel vulnerable. But the way the gazes pierce through the fourth wall that separates the invented scenes (or, illusions) from the threshold of reality makes one wonder what we are really seeing when we look at each other, or when we look into the portal of a mirror. The dual definition of “reflection,” as mirrored images and also moments of consideration, makes the show particularly resonant. This doubling effect greets me through pieces like As my grandma always used to say, don’t go borrowing trouble (2023); I feel like I’m looking into the eyes of the grandmothers I have known, while also seeing myself in their imagined visages, now a memory.

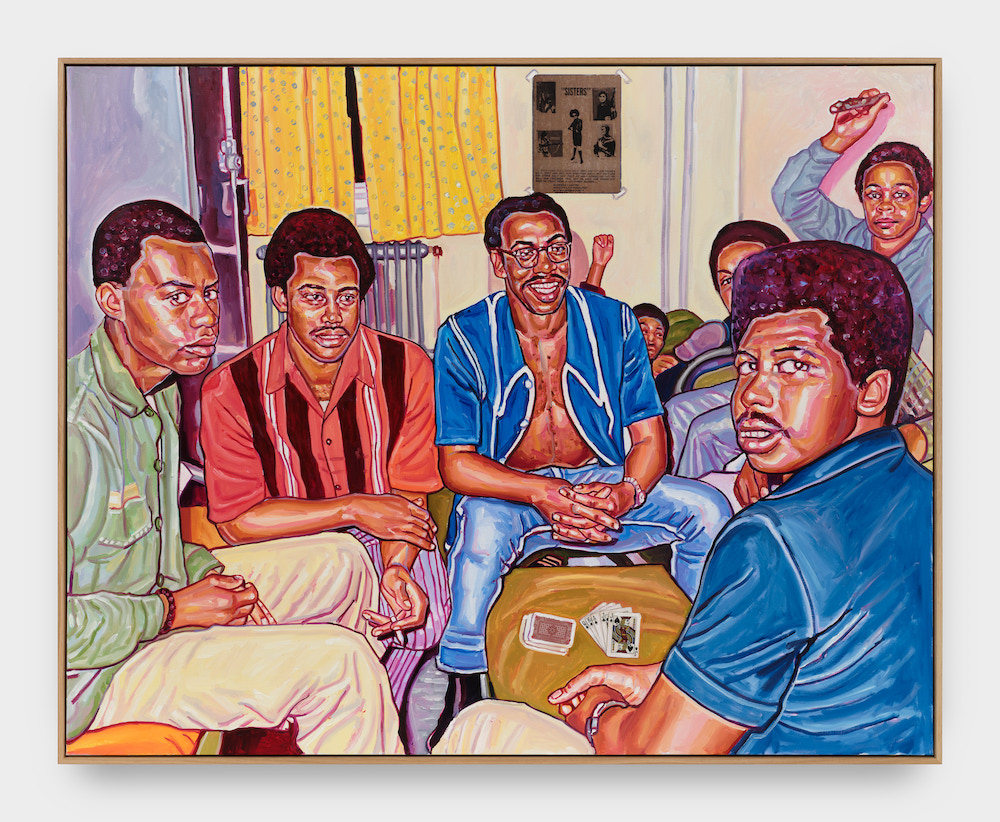

There are several miniature instances of Erheriene-Essi’s mixed-media mischief on display; many of the paintings (which are all oil, ink and xerox transfer on linen) contain pieces of recycled ephemera she has built a home for in the world of her canvases, including images of a Black Panther poster, a “Dismantle Apartheid” pin, and the Black power fist. These operate as obvious political statements in motif form, but more subtly, in A Royal Flush (2025), the artist paints a group of men playing a game of cards enjoying their last days together before deployment to Vietnam.

In E is for Everybody (2023), the image of a Black ABCs visual learning aid poster (which offered the embrace of representation to Black children in classrooms when they were first released to educators in 1970) is a reminder of how important a foundation of seeing ourselves truly is. And elsewhere in the show, Erheriene-Essi jumps decades ahead into the contemporary era: A memory from your youth (London Trocadero) (2024) is a portrait of children with their mother featuring the image of a poster from Beyoncé’s 2025 Cowboy Carter tour superimposed on top of one girl’s decidedly dated dress. This choice seems to gesture at the fluidity of time, and how the past is a prism to see ourselves—and each other—through.

Though Erheriene-Essi depicts quotidian moments, they are sneakily subversive in their challenging of what we understand as mundane. By punctuating her paintings with moments of symbolic mass media images, the artist highlights how inherently political the Black experience is. Even when these images are seemingly superficial, like an advertisement for different hairstyles in a kitchen where hair would likely be pressed and curled before church, or as unremarkable as a Nigeria Airways poster advertising the country as “Africa’s Cultural Center” seen just beyond the regal geles of presumably British-Nigerian women in the airport, they are charged with meaning.

Taken together, the 10 paintings in “Reflections” offer something deeper than mere representation—they are Erheriene-Essi’s more profound examination of what it means to be truly seen, to have your existence expressed in an artwork (which is, in effect, an affirmation) on view and reflected back to you.