In ever-mounting reports on the interlocked pandemics of COVID-19 and structural oppression, two words cyclically resound: “vulnerable” and “resist.” While the virus causes us to consider our own immune system’s vulnerability or resistance to it, it also creates or reveals metaphors for how we consider populations or political positions and actions. The immunization-related meaning of “resist” informs its political applications. Our view of “vulnerable” populations as inherently diseased became salient; because we have already socially distanced ourselves from the imprisoned, unhoused, migrants or refugees, elderly, and other “others” by placing them at society’s fringes, they are unable to practice social distancing among themselves. “Vulnerable,” while reorienting our awareness toward those neglected, can also be flattening.

When COVID-19-related closures began happening in February and March of this year, Los Angeles-based artists whose practices involve populations deemed vulnerable, or actions and expressions of political resistance, were in the midst of a range of projects. Kim Abeles, gloria galvez, Ara Oshagan, John Malpede and Henriëtte Brouwers, Cole M. James, Johanna Hedva and Audrey Chan reflected on vulnerability and resistance in light of the intersection of the pandemics and their art practices, life experiences and activism; they suggest interpretations and practices of, or alternatives to, vulnerability and resistance that help orient us toward an imaginative and mutually celebrated new normal.

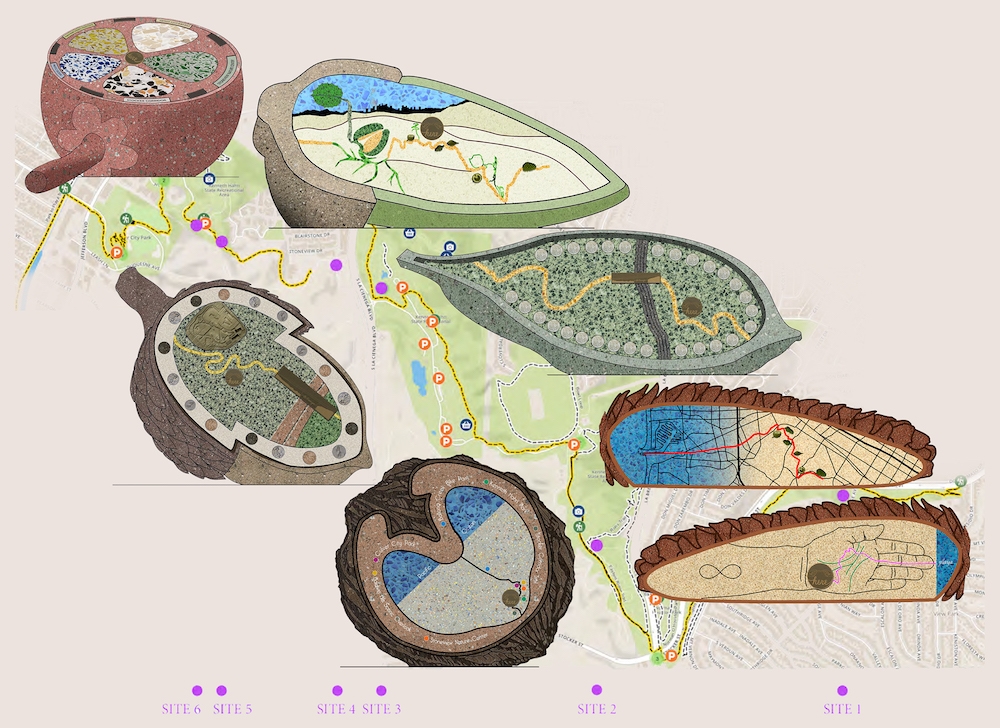

Citizen Seeds (2020). Large seed forms portraying native plants (pine, oak, bladderpod, black walnut, and manzanita) made from cast, tinted concrete. Seed interiors made of terrazzo, zinc and brass details, bronze location markers, and tinted concrete reliefs. Photo by Kim Abeles

When closures began, community-based artist Kim Abeles had been working on a Los Angeles County Arts and Culture commission to create six large seed sculptures to line thirteen miles of interconnected trails (densely traveled before safer-at-home mandates) between Baldwin Hills and Playa del Rey. The seeds, cracked open, would reveal imagery alluding to the idea of journeys, now seemingly referenced and interrupted by the protracted detour presented by the pandemic.

When asked about vulnerability, she mentioned another artwork she had recently installed outdoors that disappeared after one day. Responding to Durden and Ray’s call to 100 artists in May to mount pieces outdoors to inspire Angelenos during the pandemic, she opted to make a cover for a public bus bench in Pasadena. She photographed pinecones and pine needles at the Institute of Forest Genetics during her residency there, and then, she explained, “made [the photographs] into fabric, and stitched and padded it so that if somebody sat on it, it was soft; I did a lot of handwork.”

Abeles, who has created work for over forty years alongside survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault, incarcerated female firefighters, and on linked challenges facing unhoused people and the environment in Southern California, was clear in not placing the disappearance of her artwork and the challenges faced by the populations with whom she has worked within the same discussion of vulnerability. Nonetheless, she noted, “Putting art out there is a vulnerable state—most people put these artworks on their house or a business, maybe they knew the people, so most of the stuff was pretty protected. But [the cover] lasted a day. I saw the theft of this thing as metaphoric for what we’re all going through about this idea of loss, and what is value.”

Natural Setting (2020), at northeast corner of E. Washington Blvd. and N. Hill Ave. in Pasadena. Photo by Kim Abeles

“I see the value of people right now,” she continued, “and I also am very disappointed when I see news about people ridiculing or hurting or killing others—it’s hard to see how both of those things simultaneously go on in life. Vulnerability has to be in that place between those two things. Because of the way society makes structures for itself, we don’t give much space to things that aren’t like us, whoever that ‘us’ is. I think you have to take the stance of vulnerability these days, because you’re rewarded not to be that way.”

On the collision of COVID-19 and structural inequities, Abeles noted, “I think we’re at a spiritual crisis—it’s like when you’re an alcoholic, you’ve got to reach that rock bottom or you just don’t understand what needs to change. This coronavirus gave you plenty of social critique to look at—racism, homelessness, domestic violence, problems with the school system—it has exposed all of those more effectively than I could’ve ever done [through art]. There’s no turning back now. I keep trying to embrace work that has more of a solution base.”

Community organizer and artist gloria galvez concurred that vulnerability is a stance that is easier to elect from a position of safety or privilege. “If my safety isn’t guaranteed, and I constantly feel ‘less than,’ there’s no room for vulnerability within that space,” she said. “If my vulnerability is being honored and people are reciprocal to it, it can be a moment of transformation.”

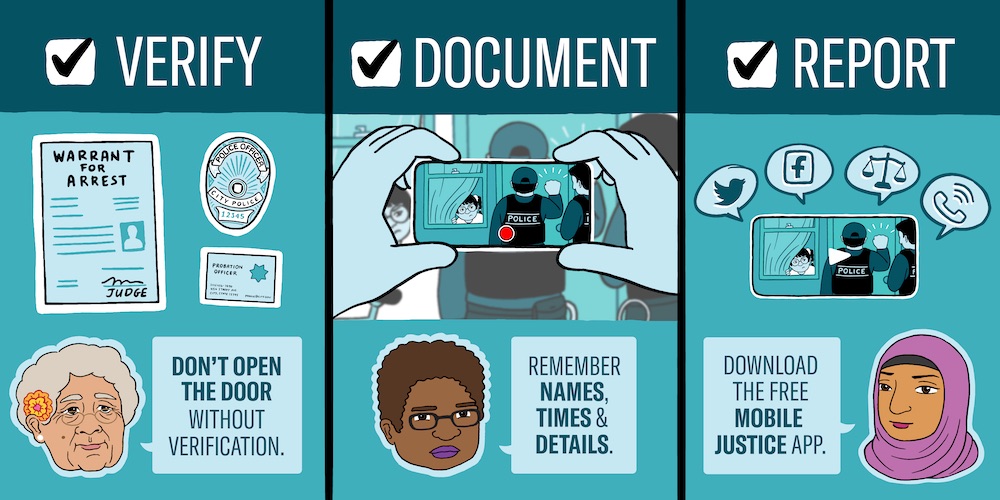

Before the closures in March, galvez had been developing a curriculum with FREE LA (“Fight for the Revolution that will Educate and Empower Los Angeles”) High School in South LA; the school was founded by Youth Justice Coalition (YJC), an organization that addresses incarceration and criminalization issues affecting youth of color and low-income youth. The curriculum, she explained, explores “object-oriented ontology, vibrant matter and animism as they relate to the youths’ day-to-day inner city experiences and their political ecological surroundings and organizing campaigns—a lot of the youth in this school are organizers.” Due to its need for students to be present in the same environment to explore and work with their surroundings, the curriculum has been postponed.

contemplations for pedagogy (2020). Items contemplated for FREE LA High School curriculum. Photo by gloria galvez

Much of galvez’s artwork stems from her organizing efforts around replacing prison and criminalization systems with community-generated redefinitions of safety and accountability, including transformative justice approaches that acknowledge the ecosystem wherein harms are perpetuated between individuals. “Vulnerability reminds me of transformative justice,” she reflected. “You think of the vulnerability of the person harm[ed]—that person has to be willing to engage with the person who did harm [and] talk about what happened, and figure out how that harm can be repaired or transformed to a more positive situation. The person who created the harm also has to be vulnerable; they have to acknowledge the harm they created, and how they’re going to address the harm.”

“I see defensiveness on the opposite side of vulnerability,” she continued. “Policing and criminalization acts from this defensive place, where we’re overfunding police stations. The YJC is starting an alternative 911; they’re recruiting and training people to go out and do harm reduction and conflict resolution. That’s an empowering but also vulnerable position—things can go wrong. But we’re saying we have each other’s backs and we’ll figure it out; we’re always going to think critically and in a way that addresses and gives dignity to all participating parties. We’re willing to take the risk—instead of calling the cops, I’m going to talk to you, and we’re going to create a culture of going that extra mile.”

gloria galvez at a Mutual Aid Action Los Angeles organizer meeting at a weekly food distribution site (2020). Photo by Yasmine Nasser Diaz

While “normal” and “surreal,” for many, refer respectively to conditions before and after closures began, activists like galvez have witnessed their underadopted, community-specific daily practices and concerns suddenly become the new wider-scale “normal.” “I work with this community group called Mutual Aid Action Los Angeles,” she explained, “and this group was already talking about, ‘How can we build autonomous communities [with] a culture of mutual aid, outside of systems that are dehumanizing people?’”

“The surrealness aspect of [the pandemic] is,” she continued, “all of a sudden all of these mutual aid groups popped up. Prior to this pandemic, not everybody was trying to practice mutual aid, or at least didn’t use that term. It was exciting and inspiring to see all of these efforts and political inclination, but there were moments where I was distrustful—you’re here now, will you be here tomorrow, the day after tomorrow? Because this work is long term work.”

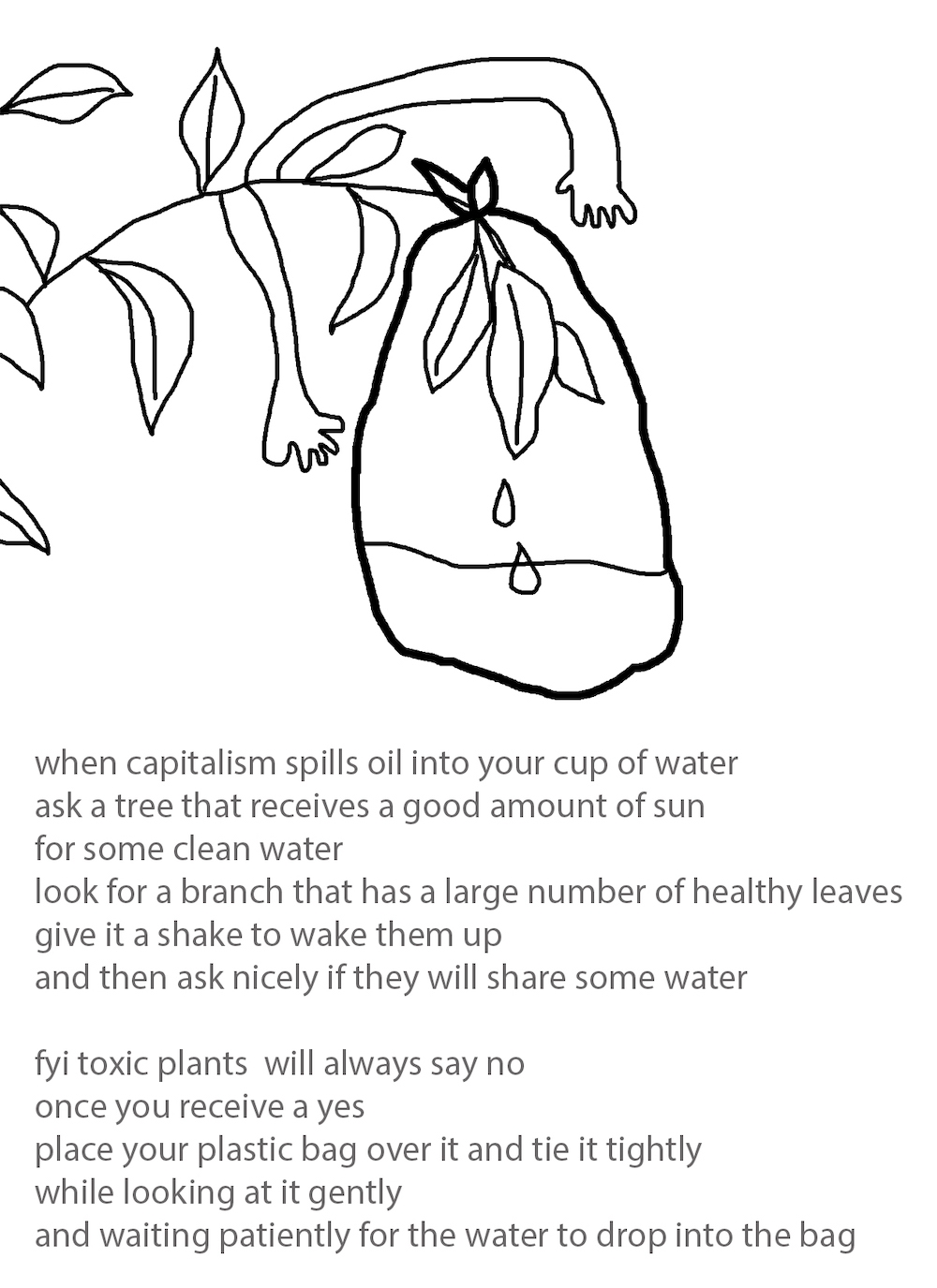

Her view on the relationship between vulnerability and resistance underscores her activist orientation. “Vulnerability and resistance are tools in my toolset for liberation,” she remarked. Having taught a class at CalArts last year on the relationship between art and political resistance, galvez considers resistance as “more than a tool, it’s also a movement. It’s a state of consciousness.” This consciousness extends, for her, to solidarity with plants as essential allies and mediums in dismantling capitalism. Before the closure, she had been working on a film titled green revolution that references plant-based survivalist strategies now unexpectedly relevant to weathering pandemics.

clean water (2020). Digital drawing produced in conjunction with green revolution film. By gloria galvez

“Just because I’m making space for vulnerability, I’m not going to let go of resisting,” she stated. “We’ve got to be vigilant and make sure the ‘-isms’ aren’t crawling in—to me, it’s really hard to separate racism from capitalism and sexism. A lot of my friends right now, when we write emails, have been writing, ‘stay fierce,’ ‘stay dangerous,’ because that is so important. I can practice vulnerability with a balance of staying dangerous to the systems of oppression—that’s what I’m personally trying to practice.”

Artist and ReflectSpace Gallery curator Ara Oshagan also views vulnerability and resistance as complementary tools, especially within the context of exploring and maintaining personal identity, as much of his work centers on geographic boundary-crossing bodies. At the time of the closures, Oshagan had been preparing for shows along Korea’s Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), in Armenia, and in Los Angeles’ Grant Park on the subjects of borders, diasporic identities and Korean comfort women. (All shows have been postponed due to COVID-19.)

“I think of vulnerability in a personal sense, in terms of space in which you can find empathy, connectivity, [and] you’re open to the world,” he said. “When I think about vulnerability and resistance, they are closely related in a process of trying to understand your life, to unravel who you are. What is your narrative, and has it become part of the general narrative? [For] Armenians, the answer is, ‘No.’ I need to resist the erasure of my own narrative and place it into the conversation as much as I can. And to do that, I need to be vulnerable, open, have my antennas out in the world and be able to be influenced and influence at the same time. So, I think [vulnerability and resistance] go hand-in-hand.”

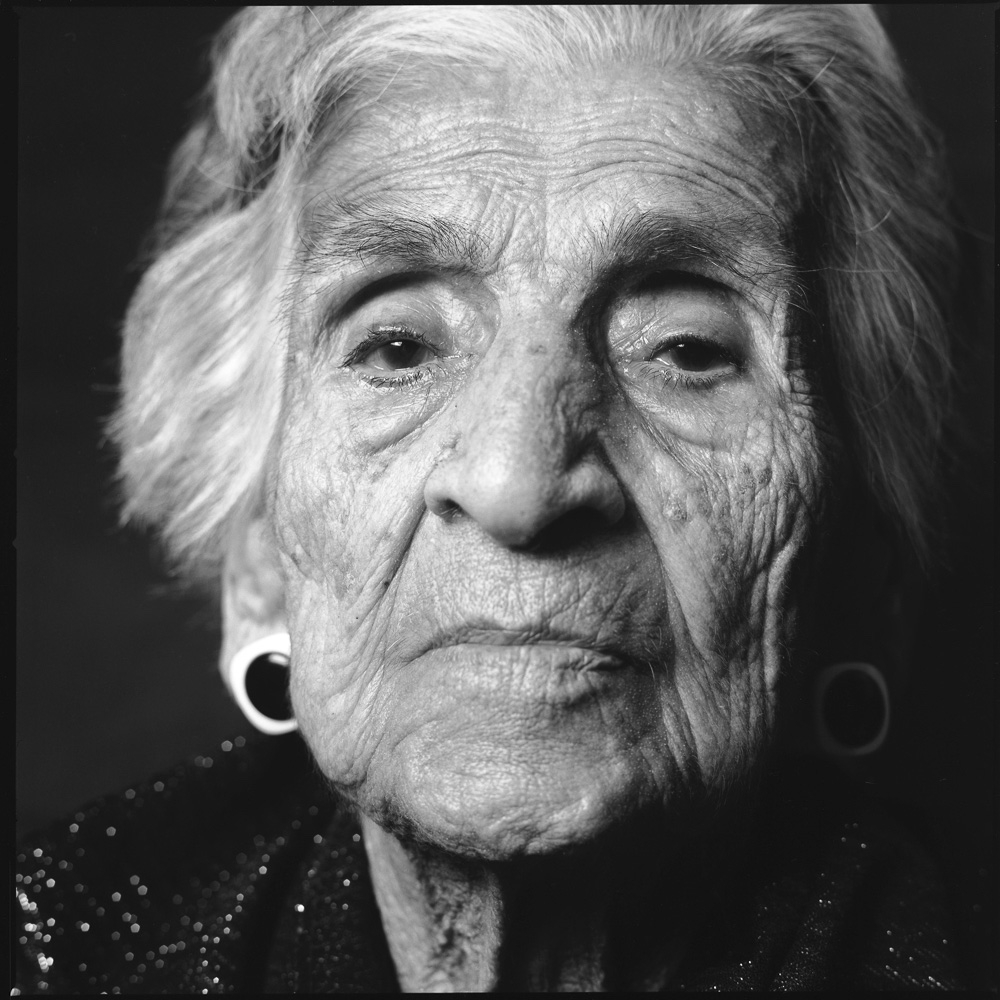

Armenouhi Bedrossian, Born 1894, Aintab, Western Armenia (1996). From iwitness: Armenian Genocide Survivor series. Photo by Ara Oshagan and Levon Parian

While Oshagan’s artwork involves populations among or situated similarly to those considered most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to political oppression or marginalization, Oshagan refuses to view them as victims. “I never think of the populations I work with as vulnerable, because I work with them today,” he remarked. “Back in the nineties, my friend Levon Parian and I started taking portraits of Armenian genocide survivors. There are some portraits that depict survivors as being weak. We have been against those kinds of images. I wanted to show resilience—the ones looking you straight in the eye, saying, ‘I survived.’ ‘Survivre’ is French; ‘sur’ is above, ‘vivre’ is to live, so they were able to ‘live above’ the death around them. I’m much more interested in those images of resistance.”

Former Comfort Woman Lee Ok Sun (Boeun) (2019). From the Keepers of the Narrative series. Photo by Ara Oshagan

“Same with the images I have of comfort women,” he continued. “I always think of them as resistance and resilience in the face of unimaginable odds. Historically, they would be vulnerable because of colonization [by] Japan, but my approach to them is never, ever to consider them vulnerable now, not to show them in that light.”

South Korean Activists for Comfort Women (2019-2020). From the Keepers of the Narrative series. Collage by Ara Oshagan

This resilience, he feels, characterizes immigrant communities in general, and notably his community of Armenians in Glendale who were not as disoriented by the COVID-19 pandemic as others unaccustomed to recurring adversity. “I’m Armenian but was born in Beirut,” he related. “We fled the war and I came [to the U.S.].”

“In Armenian society,” he continued, “when somebody asks how you are, the answer is literally, ‘Nothing.’ It’s open for interpretation—my interpretation is that because of the constant upheaval, displacement, war and attrition in Armenian history for 1,500 years, ‘nothing’ is really short for, ‘nothing bad has happened to me today.’ You’re always ready that something is going to disrupt your life.”

The pandemic, he said, was “taken very much in stride; the Armenian community in general didn’t get very panicked. Armenian stores, the micro-economy we have in Glendale, they were fine—you could buy whatever you wanted, throughout the time people were fighting over toilet paper. So, there’s this attitude that that kind of history and immigrant experience brings, where you know trouble is right around the corner, and there it is, so you deal with it.”

Los Angeles Poverty Department’s founding Artistic Director John Malpede and Associate Director Henriëtte Brouwers also champion the resilience of the Skid Row community with whom they have worked for decades. “Resilience is the word that’s been used about Skid Row for years and years and years and years,” Malpede commented. “They had to be resilient, because they had been abandoned in so many ways. If it weren’t for resistance, standing up for the community, it would’ve been displaced. It’s in the center of LA and there’s so much money to be made by displacing it.”

Freeze the Squeeze (Feb. 19, 2020), a Skid Row Now and 2040 coalition action in Skid Row to oppose the Department of City Planning’s community plan, DTLA 2040. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Poverty Department

He continued, “We have friends we’ve worked with [in Skid Row] that have been in the same hotel for twenty-five years. Over sixty percent of the population is permanent. [In] a few of the programs where people are transitioning out of state prison or drug recovery programs or domestic abuse [there are] about 3,000 people. Maybe 8,000 people in the hotels.”

Brouwers noted that while people in Skid Row are labeled “vulnerable,” “outcast,” “criminals” and “drug addicts,” Skid Row is “the only community where people know and support each other, and are resilient and very creative. It’s the only community where you walk down the street and everybody says ‘hi’ and hugs.”

Skid Row’s resilience was acutely tested during the pandemic. Malpede noted, “The Catholic Worker that has continued to feed people [in Skid Row] since the seventies, a lot of their volunteers are older, so those people weren’t coming.”

Brouwers added, “The missions that used to provide lunch and dinner started to only do takeout lunch bags. Then the Union Rescue Mission just brought everybody inside; at a certain moment somebody brought COVID-19 from outside, and all of a sudden there were seventy people infected. There are 1,000 people using fifteen bathrooms a day; on the borders of Skid Row like on Main Street, a few of those were set on fire by people that live on Main Street because they don’t want toilets for homeless people that live on their front door. There were no places to wash your hands or even have water; it was completely overwhelming. Finally, a judge said handwash stations that were promised had to be implemented, but that was weeks after the first alerts and shutdowns happened.”

Plans of Our Own – Community Responses to the DTLA 2040 plan panel (Jan. 27, 2020) at Skid Row History Museum and Archive, with Tak Suzuki (Little Tokyo Service Center), Doug Smith (Public Counsel), Sissy Trinh (Southeast Asian Community Alliance), Steve Diaz (LACAN) and moderator Rosten Woo. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Poverty Department

“‘Helpless’ doesn’t necessarily refer to the person [in Skid Row],” Malpede opined. “If the people that are authorized to do stuff don’t do it—they abandon you and their responsibilities—who’s helpless? The people [in Skid Row] aren’t helpless, they’ve done everything they can possibly do. What’s been revealed as ‘normal’ in the U.S. is what a lack of resilience there is in the systems we have, because everything has been stripped to provide maximum current profit.”

Brouwers agreed. “The way the system is built up in America is completely vulnerable,” she lamented. “Once people don’t have work for one month, they are already out on the street, and they can’t go to the hospital and pay their bills. That’s vulnerability—there’s no social safety net.”

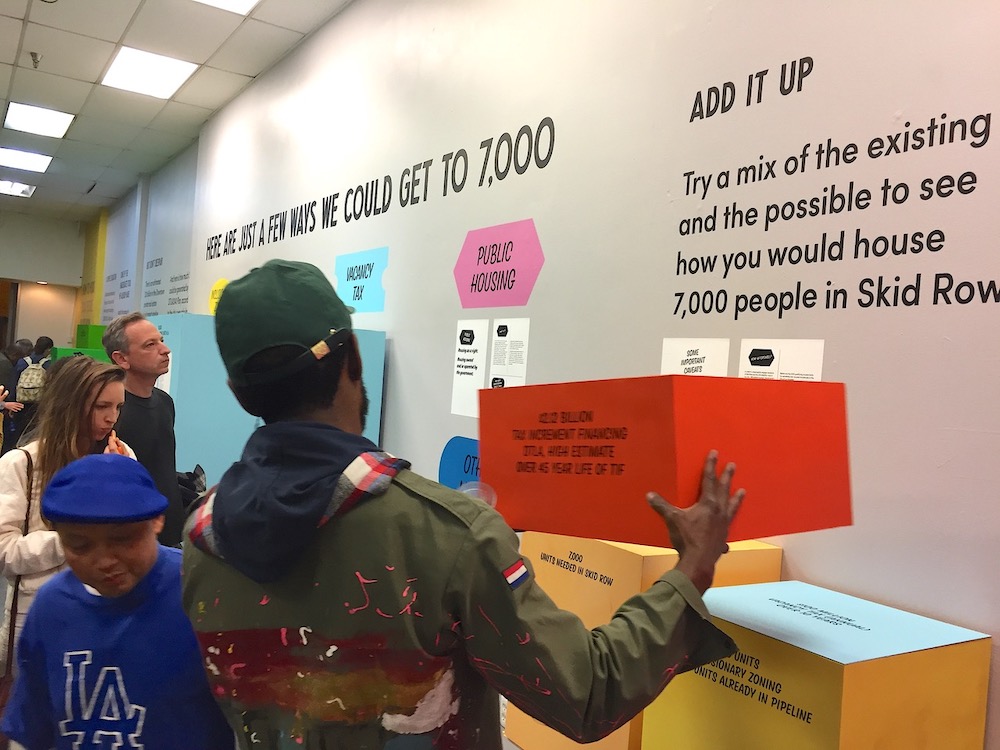

Los Angeles Poverty Department had held public talks around and opened their show, How to House 7,000 People in Skid Row, at the Skid Row History Museum and Archive just days before March shutdowns began. Brouwers explained, “We’d been working on that project for the last five years with other grassroots organizations to create our own community plan, Skid Row Now and 2040, because there’s a plan, DTLA 2040, which is part of the rezoning and recoding of all of Los Angeles. So, we started a coalition because we don’t want our people to be displaced.”

Opening night, How to House 7,000 People in Skid Row by Rosten Woo, Anna Kobara and John Malpede and Henriëtte Brouwers (Mar. 7, 2020). Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Poverty Department

Malpede elaborated, “In the seventies, [the City of Los Angeles] created a fifty-block area for no market-rate housing. In 2003, there was a community plan that allowed market rate housing to be built between Main Street and the west side of San Pedro Street. In this current plan, they wanted to make all of Skid Row open up to market rate housing. Through our conversations with [the Department of City Planning], now still all of it is market rate, but ‘forty percent of that we’ll save for affordable housing, but we want the boundaries to remain the same.’ So that’s what’s going on.”

“So, we created that ‘zone’ with the Department, and the exhibition looks at all the other ways you can generate money or zoning to create affordable housing that is so needed,” Brouwers added. “This exhibition really zoomed in on the numbers; funding mechanisms don’t exist in the city of Los Angeles because there’s no public housing anymore—everything is linked to developers.”

Otis faculty member and community-based artist Cole M. James also prefers to cast “vulnerable” populations in a different light. When the closures occurred, they had been working with the Liberated Arts Collective, which was formed through the Youth Justice Coalition with a focus on formerly incarcerated people in transitional housing, and preparing for shows at the Vincent Price Museum and California Lutheran University. “Since we can’t start on my solo show at the William Roland Gallery at Cal Lutheran,” they explained, “I did a talk with Robin Holder, ‘Can We Talk About This: On Race and Culture [in This Cultural Moment].’ I appreciate that people I had already set up an established work with wanted to talk about what was current.”

“On the news, when they say ‘vulnerable,’” they continued, “what if we just replaced that with ‘oppressed?’ These populations are not vulnerable, they’re actively being oppressed. I’m not radical and angry and frustrated about it—I just want people to call it what it is.”

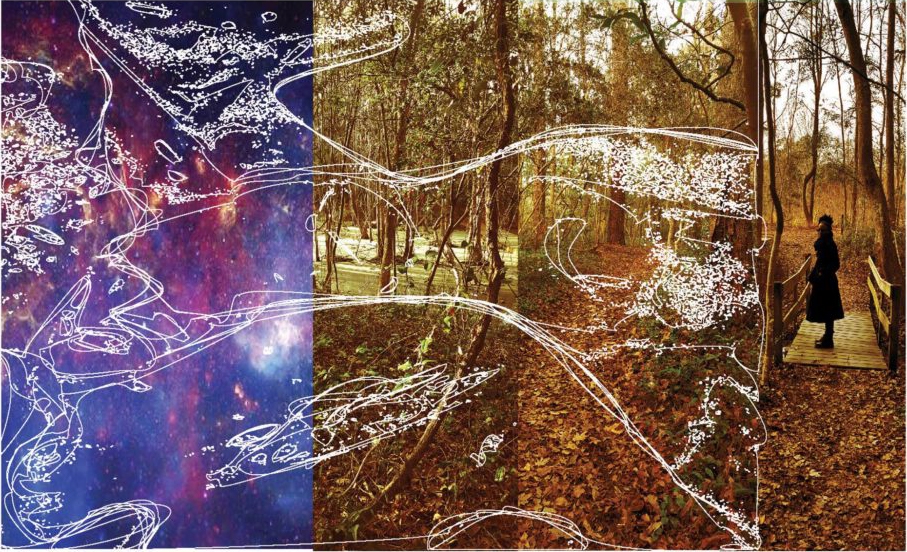

With respect to vulnerability practiced by individuals, James reflected, “Part of the great amount of strength that I have inside me is because I’m always pretty vulnerable—I’m strong but I’m not hard. I don’t view vulnerability as a weakness; I get closer to people in that way.” This receptivity extends for James to a spiritual plane. “I felt like I was preparing for this [COVID-19 pandemic] before this happened,” they said. “I was making connections to and buying things I felt like I would need [in quarantine]. I had collected all of this watercolor paper for some reason. I bought this book about color and tarot, and there are these things called veves in voodoo, they’re like drawn spells. So, I started drawing and painting these spells, and it became part of the publication East of Borneo.”

Cole M. James. Within A Universe (2019). Digital Print. Courtesy of Cole M. James

With respect to resistance, they take a stronger stance. “Every day, I have to resist the urge to believe what is said about me throughout the world. People of color are resilient by nature, because we’ve had to be to fight white supremacy in every arena and aspect of our lives,” they remarked. “Resisting in regard to protests and government activity—there is nothing to ‘resist,’ we just have to shut it down. ‘Resistance’ is almost like saying, ‘I denounce that’—you’re really not doing anything about it. If you say, ‘We will not tolerate,’ that implies action. ‘Resistance’ is, you’re still tolerating a certain amount of tension that you’re pushing back against. I don’t want people to push back. I want people to shut it down.”

Rather than push back as an outsider, James is invigorated by the possibilities of transforming institutions from within. “Since I’m the only self-identified Black full-time studio faculty doing what I do at Otis,” they said, “I’m on every diversity inclusion space, and right now all of those committees are on fire. I don’t for a second want to be assimilated, so it’s really important that I keep that transgressive practice of being inside institutions and transgressing while in them, especially institutions rooted in what they would consider diversity of thought. It’s like, can you actually be held accountable for that? Otis is doing some really good things—they’re making decisions that hopefully will keep us afloat, as well as doing the best they can to promote equity.”

Cole M. James. Non-Linear Story Building Workshop, California African American Museum Makers Fest (2018). Photo courtesy of California African American Museum

On the intersection of activism and acting as an artist more broadly, James remarked, “If you’re an artist, I wonder if everyone’s thinking about the most effective way to impact change. Artists have to be held accountable for who and what they are. One of my decisions to move to Inglewood is so that I could work in a Black space, and be surrounded by Black businesses and people, because I know there’s an entire wave of people moving to Inglewood that are not Black. I need to make myself seen and take up space, and invite other people like me to come take up space.”

On the current uprisings against racism and police violence in particular, James reflected, “No one would question whether there is generational trauma with Holocaust survivors and their families, but the expectation is that Black people, after 400 years of continual systemic oppression from the government of the United States, have no generational trauma.” Pointing to our ongoing reliance on digital screens while indoors, they further noted, “There’s a truth about the Civil Rights Movement—the reason it happened was because of television. And the protest against Vietnam happened because of television. So, it’s reasonable to say that because people are at home looking at screens all day, every day, they are seeing things they might not see at a pace they are probably not used to. So [today’s uprisings are] traveling the trajectory [of] previous movements.”

Cole M. James. Manchego Video Still (2016). Photo courtesy of Our Prime Property

For James, the safer-at-home mandates provided a welcome respite. “I was so tired,” they sighed. “Not because of the good stuff, like artmaking and shows—I got so tired of the constant, daily, emboldened racism I was experiencing. It would be when I’m walking down the street, when I go to a bar, when I sit down at a restaurant, all the time. I made a whole video called Manchego about what it’s like to move through the emotional labor of making decisions as a Black person.”

“I’m still tired of watching police officers do what they do,” they continued. “So, when we were asked to just shut down and stay inside, that wasn’t a problem for me. To identify as queer, to appear woman, but identify as nonbinary, it’s just a lot. So, it was a welcome break, because I was flat out tired.”

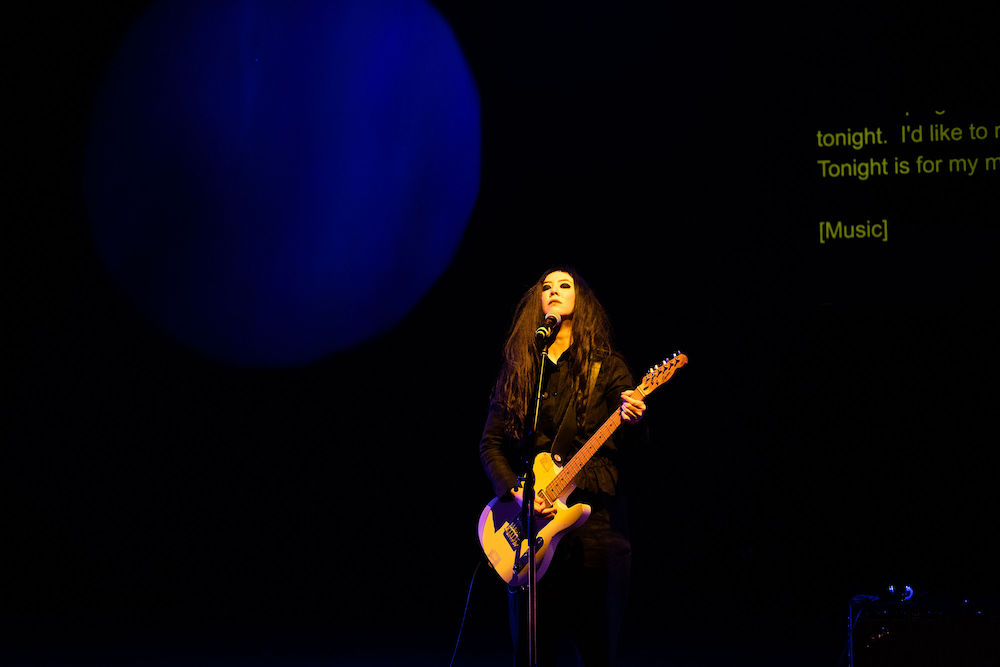

Author of essays Sick Woman Theory (2016) and Get Well Soon! (2020), the latter responding to COVID-19, artist and performer Johanna Hedva prefers to nix “vulnerability” and “resistance” altogether. Hedva, while Los-Angeles based, is immunocompromised and currently living in Berlin due to the exorbitant cost of US health care. “I don’t like the word vulnerability, I feel it’s been coopted by middle-class white women, cis women,” they remarked. “I think I prefer ‘permeability,’ to describe how the body is interdependent and formed; what illness reveals is how deeply dependent we are.”

“One of the myths of capitalism, of white supremacy, of a certain ideology that’s everywhere,” they continued, “is a very ableist one in that it insists we’re individually sovereign, and it’s only in this state of exception and rare and temporary where you’re going to need help. But then, you’re in debt to those who gave you help. There’s a binary between give and take when it comes to care, and that’s total bullshit. To get into and unpack that is to really understand how we think of debt in our capitalist society.”

Johanna Hedva performing Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House at I wanna be with you everywhere, a disability festival at Performance Space New York (2019). Photo by Mengwen Cao

In their work, Hedva challenges binaries and hierarchies of ability and disability, and illness and wellness.

In Get Well Soon!, Hedva illuminates how the interminable “stuckness” induced by illness, signaling the need to put care before other action, might parallel and guide the trajectory of social revolutions. In their essay, they write:

[I]llness and revolution both exist in similar kinds of time, the kind that feels crushingly present…. In revolution…time froths around the fact that the time is now…. The promise of change, the zeal for a new tomorrow….

At some point, though, the revolutionary now shifts toward the now of illness…waiting for change to come, waiting, still, waiting. Conversely, as many chronically ill and disabled folks know, the now of illness…reveals its subversive power, and produces a politic.

We tend to place…illness…on the end of inaction, passivity, and surrender, while revolution is on the end of movement, surging and agitating. But maybe this spectrum is more like an ouroboros: one end feeding the other, transforming into, because of, made of the same stuff as the other….

Now might be a good time to rethink what a revolution can look like. Perhaps it doesn’t look like a march of angry, abled bodies in the streets. Perhaps it looks something more like the world standing still because all the bodies in it are exhausted—because care has to be prioritized before it’s too late.

Johanna Hedva, from Sick Woman Theory published in Mask Magazine (2016). Photo by Pamila Payne

Hedva noted, “In the last several years, I’ve been committed to doing accessibility in my art practice as well as my day job. If a museum or gallery contacts me to do a performance or an exhibition, I send them my disability access rider first and say, ‘Please tell me how you can or cannot support each thing. And if you cannot support it, that’s okay, I want to have a conversation about it.’”

Like galvez, Hedva noticed their typically marginalized “normal” swell during the COVID-19 pandemic. “The mutual aid that I saw emerge in communities that are normally staunchly autonomous was like seeing a weird mirror,” they observed. “[The pandemic] was an experience of watching the daily concerns that affect me and my fellow disabled friends scale up dramatically to affect the whole world in a way that the world is not used to. One phrase I’ve been using to describe it is the ‘blast radius of disability,’ which is explosive, it radically changes your perception of who you are and how the world works.”

When asked about the parallel pandemic of racism, particularly anti-Black racism within Asian American communities, heightened by the conspicuousness of an officer of Asian descent standing by in the killing of George Floyd, Hedva reflected, “I think the issue around anti-Blackness within Asian American communities and generally non-Black people of color is a serious and gravely under-addressed issue. It’s not just white supremacy, it’s also anti-Blackness, and I think the relationship of those two cannot be separated. As a Korean American person who is incredibly white-passing, I notice how whiteness and white supremacy and anti-Blackness are kind of infested in me. ‘Infestation’ gets at the horror and the violence and the uncanny, spooky quality of how these ideologies get into you on a cellular level. It’s not just some position that you think, it is embodied.”

Johanna Hedva, from their essay In Defense of De-persons published in GUTS Magazine (2016). Photo by Pamila Payne.

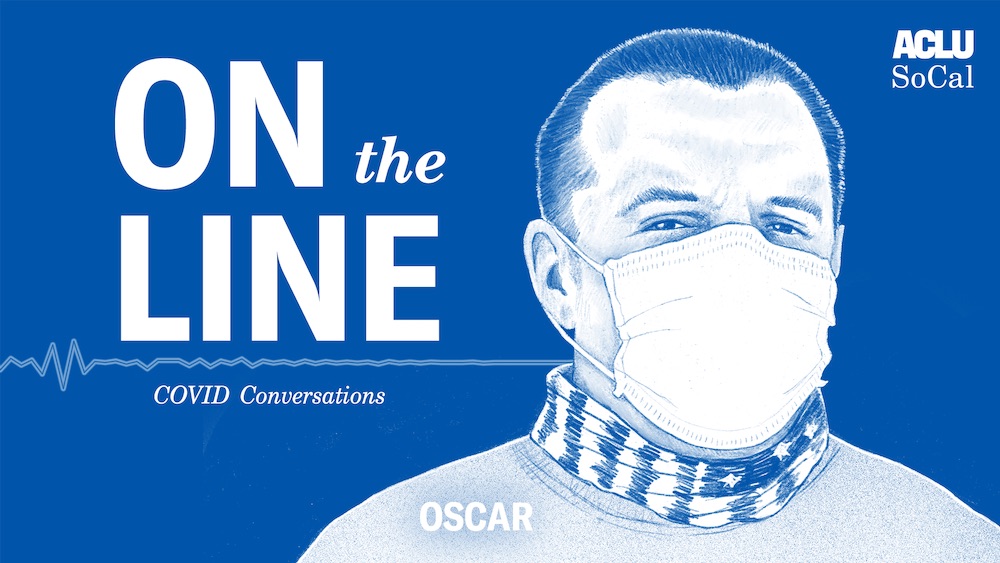

Finally, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Southern California’s inaugural Artist-in-Residence Audrey Chan also responded personally on the convergence of anti-Asian racism stemming from the attribution of COVID-19 to China, and anti-Black racism. “Race is woven into the everyday life of my family because my husband and I are raising a Chinese-Jamaican son in an America entrenched in the culture of white supremacy and erasure,” she wrote via email. “Our daily conversations are deeply grounding and the lens through which we are processing both the pandemic and the powerful civil uprising for Black lives. We’re doing our best to raise our son, supporting community-based organizing, and staying focused on our writing and art projects that focus on uplifting the narratives of underrepresented communities. Storytelling is our way of moving and making through this time. Solidarity is our everything and will continue to be in the days to come.”

She named several Asian American artists whose responses to the pandemic have countered the narrative of disease bearers or culprits, including “Devon Tsuno, who has converted his painting studio into a 3D-printing PPE-production factory as part of the global movement of makers supporting frontline workers; Kristina Wong, who recently premiered her phenomenal and complex one-woman show ‘Kristina Wong for Public Office’ and is now leading the Auntie Sewing Squad, a coalition of volunteers that has produced tens of thousands of fabric face masks for vulnerable communities; Laura Chow Reeve of Radical Roadmaps, who makes stunning infographic drawings to visualize the strategic conversations of progressive organizers; and Amy Uyematsu, whose 1969 essay ‘The Emergence of Yellow Power in America’ continues to be a guiding light and whose poetry is unflinching in how it responds to the times.”

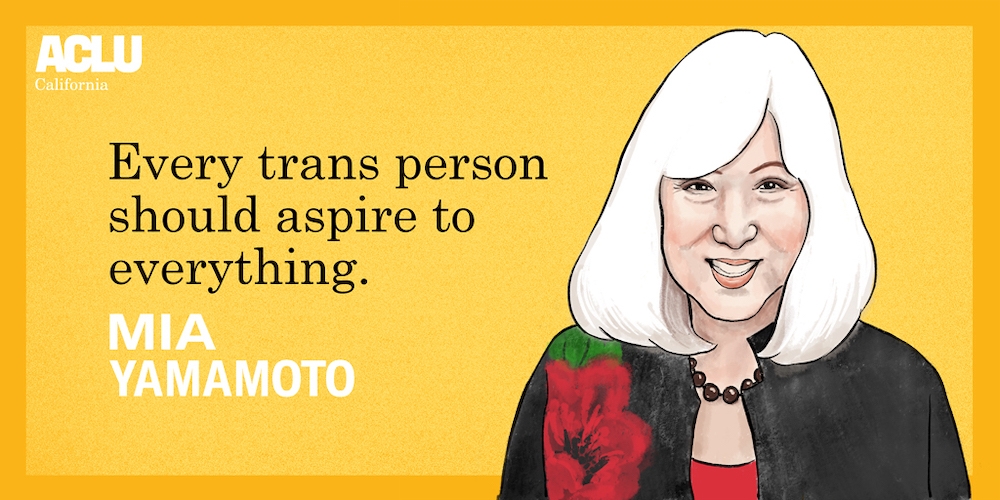

Portrait of Mia Yamamoto (2020). Digital drawing. Image courtesy of Audrey Chan/ACLU SoCal

Chan related that, since her residency began last October, she and ACLU SoCal have “been working together to find ways for art to amplify the organization’s ongoing fight for structural change, which is in high gear on all fronts at this moment.”

“The question of vulnerability,” she reflected, “is intertwined with the question of: who is protected, what systems and structures exist to allocate or withhold protection, and who maintains or challenges those systems and structures? On the one hand, all people are (or should be) practicing hypervigilance to avoid the invisible contagion of COVID-19. On the other hand, people from marginalized communities also have had to internalize a level of hypervigilance as part of daily life to move through spaces that are overpoliced by both law enforcement and so-called ordinary citizens.”

Poster for ACLU SoCal’s “ICE Not Welcome” Know Your Rights campaign (2020). (English: “This is our community. We know our rights. We do not consent. ICE is not welcome here.”) Digital drawing. Image courtesy of Audrey Chan/ACLU SoCal

“The residency has been an opportunity to learn that the most pervasive threats to the American democracy come from within—police violence and impunity, racist immigration policies, exploitative systems of labor, legalized discrimination, and a lack of basic protections like shelter and safety,” she continued. “I have learned that resistance and resilience are values that come from within communities who deeply understand their own needs but who don’t have the support, protection, and generations of accumulated wealth to realize the standards of well-being they deserve. I think it’s imperative for artists to be engaged in these processes of demanding accountability, tugging at and unraveling hardened positions, and activating all of our senses and faculties in the head and heart work of social change.”

Social media graphic for ACLU SoCal’s “ICE Not Welcome” Know Your Rights campaign (2020). Digital drawing. Image courtesy of Audrey Chan/ACLU SoCal

When the shutdowns began, Kim Abeles had also been working on a smog-related project, stemming from her decades-long work utilizing Southern California smog as a medium for illustrating the causal chain between human activity and environmental degradation. She initially intended to place her 15’ x 5’ version of Smog Catcher—an illustration of herself holding up her skirt to catch the falling sky—outside Keystone Art Space’s entrance in downtown LA, but dismantled and placed it in her studio there when the building closed. While the names of some of her prior pieces reflect the number of days they were left outdoors to collect smog, Abeles updated the name of this piece to include the number of days it was quarantined. (In retrospect, she mused, she could have left it outside, to capture evidence of improved air quality while fewer cars were on the roads.)

Smog Catcher perhaps reflects the lenticular nature of the relationship between vulnerability and resistance: the girl holds out her skirt to catch the falling sky, anticipating a kind of peril that is toxic yet self-created (or, what she herself is made of); she stands with a readiness to meet it that is at once receptive and defensive. Quarantined, while less imperiled by indoor smog, she is quite literally broken down; the shelter at once protects and confines or cages her. Through Brouwers and Malpede, Oshagan, James and Chan, we witness another lenticular alternation: marginalized populations are from one angle vulnerable, and resiliently resist oppression from another.

Smog Catcher (6 days of smog, 1 day of rain, and 8 weeks exposed indoors during quarantine) (2020). In process photo, smog (particulate matter) on wood panels. Photo by Kim Abeles

The pandemic disorients us within this kaleidoscopic matrix or pulley system of harms and salves, allies and foes, and causes and effects. We thought we were helping the environment with reusable bags, but we are now prohibited from bringing them into stores to protect our own health; to protect our own health, we now also view disposable masks and gloves, and ecosystem-destroying chemical sanitizers, as “essential.” We had been admonished against too much screen time at the expense of physical interaction, and now that advice has flipped. Pharmaceutical companies condemned for catalyzing opioid addiction stand to become heroes through distributing COVID-19 vaccines, while sizable contingents of opposing political parties have emerged from their respective echo chambers in a rare show of solidarity to oppose all vaccinations.

We understand that social distancing is vital to curbing the spread of COVID-19, but hundreds have protested with locked arms in public, for days on end, perhaps because the risks posed by systemic racism are in some ways more life-threatening than, or exacerbate, the risks posed by COVID-19. Many of these protestors condemned others who congregated sans masks to demand that states reopen. Before COVID-19 became a global pandemic, the prison industrial complex was already considered one, but those who stand for abolition on one hand might, on another, demand the imprisonment of particular wrongdoers, e.g., the police and other state actors. It’s hard to whack all the moles or societal demons at once and for good; knocking one down seems only to thrust the next upward. Vilifying something absolutely, on its face, either ignores its vital function in another context, or ends up most harshly stinging the accuser.

“The dawn came, but no day.” (2020). From The Dawn Came, But No Day series. Digital collage printed on linen. Text from Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck. Right: Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange. Collage by Ara Oshagan

What the pandemics and their series of “Sophie’s choices” bring into relief is the inherently exploitative and violent infrastructure we have created to support what we consider meaningful human activities. If we had set up a world where we each, say, found in nature all the food we ate, we would not have to choose between disposable or reusable bags at grocery stores. If we had set up a world without systemic oppression, we would not have to choose between public demonstration, imprisonment and social distancing. It may be naïve to romanticize and return to a time predating “civilization” or industry; but, acknowledging our antagonistic infrastructure—where exploitative competition between individuals’ desires, and between human desires and nature, is the premise—might help us lay groundwork for a more equitable ecosystem or “normal” ahead, where we don’t need entrenched winners or losers in order to meaningfully live.

compost money (2020). Digital drawing produced in conjunction with green revolution film. By gloria galvez

When we consider “vulnerability” and “resistance” as gateways or pointers to more expansive or potential-rich energetic fields, rather than words or parcels of property over which ownership is volleyed and won or lost, they converge on what feels like the choice and process of a third term: engagement. Engagement entails marriage, wrestling, or often both. Engaged, whether in love or battle, each participant is engrossed in the other’s energy, or fully exposed to and present with the other.

When vulnerability and resistance meet in engagement, they yield, not unperturbed union or cancel culture warfare, but sustained responsiveness grounded in heightened awareness. When we engage, we go beyond reactivity; we bring our whole selves and energy to meet our match (in battle or love), whom we fundamentally respect as our equal. While idealizing this kind of engagement might create anxiety around doing it “correctly,” the greatest potential of engagement lies in the sustained willingness to simply “stay with” another. This willingness may need to weather awkwardness, uncertainty, intimidation, contradictions, fatigue and periods of hiatus and recuperation, but it can endure through the elasticity of the intention to “stay with,” which arises out of an uncomplicated awareness of the other person’s inherent value.

Art opens worlds of engagement; its functions of critiquing, uplifting and inventing worlds are arguably equally important. James’ practice of positively transgressing within art institutions, galvez’s embrace of vulnerability as central to transformative justice approaches that resist the prison industrial complex, and Oshagan’s view of vulnerability and resistance as powerful allies in ensuring the visibility and endurance of marginalized narratives, point to positive practices of engagement. In engagement, we battle and resist certain social constructions, while remaining present to, and holding sacred the value of, the individuals and natural environments in and around them, in order to arrive at new and mutually supportive normals.

Detail of Citizen Seeds (2020). Photo by Kim Abeles

We will not succeed at “staying with” others because it sounds like a nice idea; the orientation must take root as an unshakeable core commitment or belief. A spiritual and emotional intention to “stay with” eventually and inevitably arises out of thorough honesty, the kind that subordinates judgmentalism to the complex veracity of raw and deeply held emotions. In practicing engagement, we may initially expect to tolerate or learn more about those with whom we disagree. But the power of thorough honesty is in its mirroring potential (as artists who center personal honesty in their practices know): through others’ honesty, we see ourselves, not only how we are like them, but what we are like—that is, how we, too, enact untenable or fruitful contradictions, and are complicit in our shared reality.

This level of intimacy with others and ourselves, in disarming our defense mechanisms, makes room for nuance and discernment. Capitalism and communism have both “failed” as models of government; overemphasizing competition and simply giving all children trophies have both proven detrimental to the development of resilience and a sense of our own and others’ value. When entered voluntarily in a spirit of fun, where everyone can shape the rules, competition can generate excitement, discovery, innovation and growth that inspires and supports even those who end up “losing” one round. When undertaken as a strategy to control, possess, intimidate or exterminate, competition yields “Sophie’s choices” and unintended self-destruction.

Where, as Hedva noted, revolution can draw from the wisdom of illness in an ouroboric or regenerative fashion, our current “normal”—the one that created and perpetuates our pandemics—continues to eat itself alive without replenishment. Within our larger paradigm where life and death—seemingly at odds—cooperate, or enable or define each other, derivative interdependencies of seemingly contradictory energies, like “vulnerability” and “resistance,” are par for the course. Through engagement, we can consciously and artfully exercise, and exorcise demons through, those energies toward mutual benefit, rather than be pinned into one or the other through violence, reactivity and bewilderment, toward annihilation.