It was really a break from a break from a break from a longer art project (which is what art features turn into after they’ve been festering and metastasizing for more than a month or two) that brought me out to Bel Ami – a gallery I’d never been to located in the same Chinatown building that houses the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive—next door in fact, which may or may not have had something to do with the scrum my pal and I walked into for what was ostensibly the opening of a show of (mostly) paintings curated by the artist, Lucy Bull (herself a formidable painter)—who I was almost surprised hadn’t included herself—she would have been in good company.

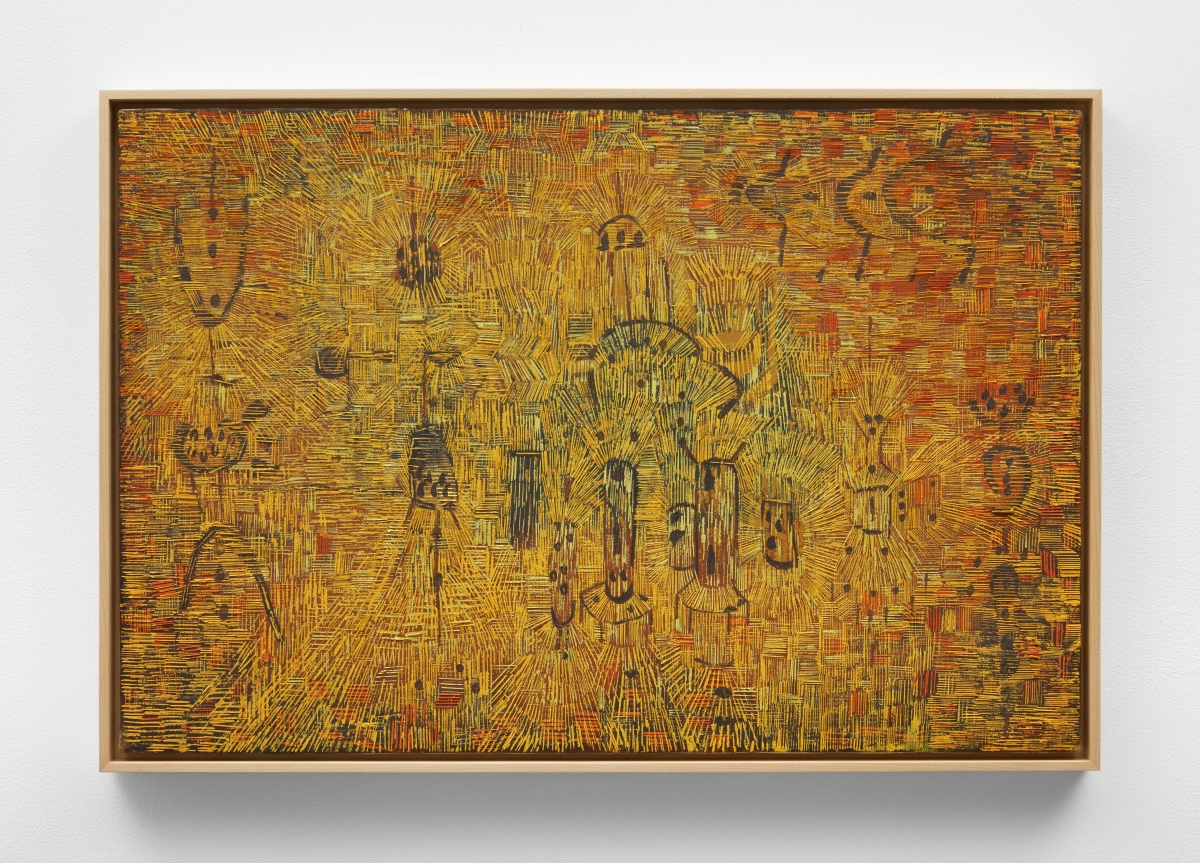

Lee Mullican, Untitled (‘marble’ drawing, c. 1969) oil pastel on paper

And yet of course even from what little I know of Lucy Bull’s work, I sort of understand. This isn’t simply an “Emblazoned World” (the title she gives to the exhibition, taken from the Lee Mullican “marble drawing” (really a painting—with yet another in a similar vein on view here), it’s really more of a submerged world—off the deep end and full-fathom-five, where Bull’s own work ranges into a more dispassionate, almost discursive range. But we see easily just how these works sank their hooks into her imagination. (There’s a personal angle, too: Bull came to know Mullican’s son, artist Matt Mullican; and through him and his father’s estate, Mullican’s widow, the artist Luchita Hurtado.)

Mullican’s work also has a radiance—not simply the ‘marble drawings’, but also a more classically rendered canvas exhibited here, Premier Mirage (1949), with its massed and swirling ridges and striations in yellows, grassy greens and russet hues—converging worlds of suspended geometries, vessels and biomorphic shapes suggestive of arcane rituals and animal silhouettes, from a period of Mullican’s work that continued through the 1950s and well into the 1960s. Mullican does not ignore shape in the ‘marble’ paintings and drawings; they alternately morph and undulate—as they do here in a more dual-chromatic vibrational field with blues and violets floating in a field of feathery green striations (1969)—bodies within bodies of cellular color; or fill the surface with plaited and patterned beadwork surfaces as if for an ornamented textile (Emblazoned World).

Mullican’s work also has a radiance—not simply the ‘marble drawings’, but also a more classically rendered canvas exhibited here, Premier Mirage (1949), with its massed and swirling ridges and striations in yellows, grassy greens and russet hues—converging worlds of suspended geometries, vessels and biomorphic shapes suggestive of arcane rituals and animal silhouettes, from a period of Mullican’s work that continued through the 1950s and well into the 1960s. Mullican does not ignore shape in the ‘marble’ paintings and drawings; they alternately morph and undulate—as they do here in a more dual-chromatic vibrational field with blues and violets floating in a field of feathery green striations (1969)—bodies within bodies of cellular color; or fill the surface with plaited and patterned beadwork surfaces as if for an ornamented textile (Emblazoned World).

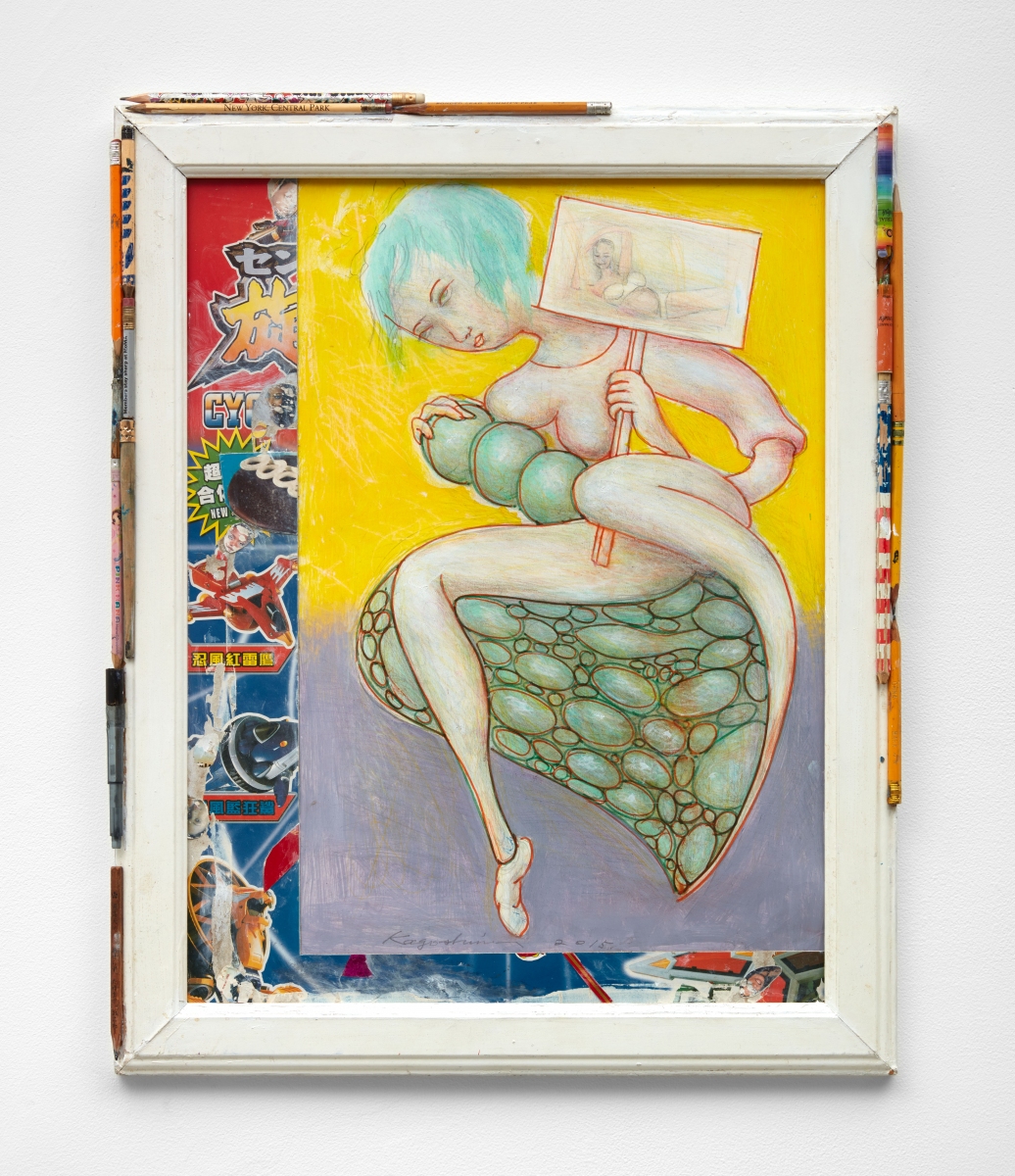

Bull also shows one of Luchita Hurtado’s (untitled) “moth light” paintings (from 1975)—which she reports were calculated to “attract moths.” Whether or not they succeeded, they draw the viewer in almost magnetically—a trench of luminosity with a white square at its center carved out of a dense grid of umber-browns and burnt-sienna. It’s a 50-year jump from Mullican’s ‘emblazoned marbles’ to Kinke Kooi’s seemingly beaded, cushiony paintings on paper with collage, equally ‘emblazoned’ and submerged—as if the collaged ‘angel’ in one holds a threatened cloister tower in place (Support, 2016), Q-tips and painted jonquil pressed into fleshy jewel cases for Visit 3 (2019); yet they might float comfortably side-by-side. E’wao Kagoshima’s demi-mondaines seem to have evolved from other worlds altogether, whether a Shibuya schoolgirl’s dream or a spider’s web in hell (yet retaining the souvenirs of this one—the pencils attached to Distortion One’s (2015) frame originating anywhere from the Dixon Ticonderoga factory to New York’s Central Park).

Bull also shows one of Luchita Hurtado’s (untitled) “moth light” paintings (from 1975)—which she reports were calculated to “attract moths.” Whether or not they succeeded, they draw the viewer in almost magnetically—a trench of luminosity with a white square at its center carved out of a dense grid of umber-browns and burnt-sienna. It’s a 50-year jump from Mullican’s ‘emblazoned marbles’ to Kinke Kooi’s seemingly beaded, cushiony paintings on paper with collage, equally ‘emblazoned’ and submerged—as if the collaged ‘angel’ in one holds a threatened cloister tower in place (Support, 2016), Q-tips and painted jonquil pressed into fleshy jewel cases for Visit 3 (2019); yet they might float comfortably side-by-side. E’wao Kagoshima’s demi-mondaines seem to have evolved from other worlds altogether, whether a Shibuya schoolgirl’s dream or a spider’s web in hell (yet retaining the souvenirs of this one—the pencils attached to Distortion One’s (2015) frame originating anywhere from the Dixon Ticonderoga factory to New York’s Central Park).

E’wao Kagoshima, Distortion One (2015) acrylic on paper, wooden frame and pencils

There is nothing in the show that doesn’t compel fascination. But perhaps most fascinating (no surprise that Bull singles it out for her statement) is Eugene von Bruenchenhein’s otherworldly oil-on-masonite panel from 1957, a kind of tempest of bristling, spined and segmented biomorphic forms that seem to float up out of a churning chasm of deep blue and luminous ambers and yellows. Redon couldn’t have painted this work, but he would have understood it. Yet there is an energy and dynamism that belongs to von Bruenchenhein alone. Von Bruenchenhein was featured in the 2018 Outliers and American Vanguard show (that was at LACMA)—but it seems almost absurd to attach such a label to work this compelling, whatever the eccentricities of the artist or the means he employed to produce it.

Nancy Lupo, Currency Exchange (2020), mixed paper, glue, mica pigment, bass wood and bamboo skewers, fiberglass mesh, graphite

Kentaro Kawabata, Seed (2021) glazed porcelain

Arrayed around these remarkable paintings, is a variety of objects that live up to such dual standards and eccentricities – from Nancy Lupo’s almost indescribable raft of tufted, flesh-colored fibreglass, paper, and who-knows-what-else (Currency Exchange, 2020), to Kentaro Kawabata’s esoteric porcelain vessels (Seed, 2021); from Guillaume Dénervaud’s cratered Mars-red moon-sphere to Elizabeth Englander’s “Bikini Crucifixions” (one of which seems to give an entirely feminist reworking of the original Christian mythology); from Nik Gelormino’s cedarwood spirals to Joseph Grigeley’s Blue Conversations (cautionary random fragments to variously inspire alarm and envy—sitting “next to Jackie Onassis” on a “10-seater plane to Martha’s Vineyard”?—can we bloody talk?!?). The young, largely unmasked crowd outside the gallery gave me some alarm on my way into the Bel Ami space. But once safely inside, this was a world I was in no hurry to leave.

Elizabeth Englander, Bikini Crucifixion No. 1 (2020) old bathing suits, steel, cotton thread

Emblazoned World — Group show curated by Lucy Bull — Lee Mullican, Luchita Hurtado, Eugene von Bruenchenhein, Kinke Kooi, E’wao Kagoshima, Elizabeth Englander, Nancy Lupo, Kentaro Kawabata, Guillaume Dénervaud, Joseph Grigeley, Nik Gelormino – at Bel Ami – 709 N. Hill Street (2nd Floor), Los Angeles, CA 90012 (Chinatown) – through October 30, 2021