Long before I had a clue about art, or at least modern or contemporary art, my older brother and I would occasionally be dropped off at twin fantasylands on either side of Central Park that, to our five and six year-old brains, were like complementary sides of what was really the same dream world. Oh yeah – there was some actual art at that Fifth Avenue circus; but our coverage of those spaces on our swift spindly legs was pretty random. We were there to (almost literally) get lost; and in the Egyptian collections of the Met, we actually did – sort of…. Really we were conscious of being surrounded by language, words, symbols, meaning and those gods and goddesses that complemented the dioramas and dinosaurs at the American Museum of Natural History on Central Park West. But we could only let it sink in with a kind of fragmentary dream logic. We were only just beginning to read English and having a hard enough time sorting through the other languages sifting into the air and media around us. Wandering through those galleries, we were conscious of being immersed in narratives of metamorphosis and transformation, a multiplicity of mythologies to parallel the narratives of science and nature – earth’s actual history – to be experienced across the Park. Finally, 20th Century Fox released Cleopatra, and everything started to come into sharp focus.

Long before I had a clue about art, or at least modern or contemporary art, my older brother and I would occasionally be dropped off at twin fantasylands on either side of Central Park that, to our five and six year-old brains, were like complementary sides of what was really the same dream world. Oh yeah – there was some actual art at that Fifth Avenue circus; but our coverage of those spaces on our swift spindly legs was pretty random. We were there to (almost literally) get lost; and in the Egyptian collections of the Met, we actually did – sort of…. Really we were conscious of being surrounded by language, words, symbols, meaning and those gods and goddesses that complemented the dioramas and dinosaurs at the American Museum of Natural History on Central Park West. But we could only let it sink in with a kind of fragmentary dream logic. We were only just beginning to read English and having a hard enough time sorting through the other languages sifting into the air and media around us. Wandering through those galleries, we were conscious of being immersed in narratives of metamorphosis and transformation, a multiplicity of mythologies to parallel the narratives of science and nature – earth’s actual history – to be experienced across the Park. Finally, 20th Century Fox released Cleopatra, and everything started to come into sharp focus.

Okay not really. Actually that long anticipated film release simply began a process of illuminating another kind of mythology or mythography unfolding around us. (By that time we had learned what mythology actually was.) Away from the society of spectacle, we could see (if not understand) in those hieroglyphics the process of myth becoming embedded within or grafted upon an actual history or drama – kernels of the kinds of drama we were also beginning to see on actual stages (or on television – or in the movies). In the meantime, the world – along with all these realities and images – flooded into our already fast-compartmentalizing minds, to be absorbed (or grafted), recomposed, reconstructed, reimagined, reinvented; transformed into something entirely new – or at least something we could handle.

To stroll through Gronk’s Theater of Paint (at the Craft and Folk Art Museum through September 4th) is to re-experience that engulfing yet continuously fragmenting and dissolving sense of metamorphosis between nature and actual history and mythology and mythography. It is an experience charged simultaneously with a freshness that is almost innocent and a great sophistication. You can get lost in a single corner of the exhibition, focusing on one fragment of a panel or stage set or backdrop, or an array of objects – there is always the sense of an interior conversation within the multiplicity of parts that compose these paintings, sets and backdrops. Or you can pull back to see how a single, emblematic gesture, a single configuration of lines and color, can become the signature or basis for an entire dramatic architecture.

To stroll through Gronk’s Theater of Paint (at the Craft and Folk Art Museum through September 4th) is to re-experience that engulfing yet continuously fragmenting and dissolving sense of metamorphosis between nature and actual history and mythology and mythography. It is an experience charged simultaneously with a freshness that is almost innocent and a great sophistication. You can get lost in a single corner of the exhibition, focusing on one fragment of a panel or stage set or backdrop, or an array of objects – there is always the sense of an interior conversation within the multiplicity of parts that compose these paintings, sets and backdrops. Or you can pull back to see how a single, emblematic gesture, a single configuration of lines and color, can become the signature or basis for an entire dramatic architecture.

Theatre has always been at the core of Gronk’s art, but theatre plays out in both actual and interior spaces: the physical, temporal space of the theatre (and the street or public space: an indifferent space – one that may or may not be noticed) and a multi-dimensional theatre of the mind. Both Gronk’s private studio practice and his theatrical collaborations play with notions of meta-, or even hyper-theatre. For Gronk, the theatre always has its double – and more. Gronk began developing this from his earliest Los Angeles Theatre Center collaborations with Jose Luis Valenzuela (where, for example, even the notional ‘magic realism’ of Stone Wedding was turned inside out into something harshly direct and physical, yet gestural and reaching for a symbolic dimension). Gronk insists upon confounding expectations; upon his own conversation with the myth, with the medium; but aso suggesting the interior conversation you might have with yourself parallel to the one going on with the action on stage.

But this goes back to Gronk’s earliest work as an artist and the work that brought him into the Chicano activist art collective, ASCO (from asco, the Spanish word for disgust, nausea or revulsion) – the ‘instant murals,’ the happenings and mini-street performances, often unannounced, the ‘no-movies’ (insistently not a movie – let’s ‘not go there’). Actions – highly theatricalized, but insistently not theatre; as much about refusal, rejection as about the actuality of participation; a gesture moving in two (or more) directions: an insistence upon acknowledgment – not recognition, but visibility, optics – being seen; in turn rejecting the simplistic strategies and tropes of identity politics; exiles on Main Street and their own street. (There’s something almost proto-punk about it, too; but Asco was sui generis. To find anything comparable in the art world of that time, one would have to look to the San Francisco Bay area, New York – or the world.)

But this goes back to Gronk’s earliest work as an artist and the work that brought him into the Chicano activist art collective, ASCO (from asco, the Spanish word for disgust, nausea or revulsion) – the ‘instant murals,’ the happenings and mini-street performances, often unannounced, the ‘no-movies’ (insistently not a movie – let’s ‘not go there’). Actions – highly theatricalized, but insistently not theatre; as much about refusal, rejection as about the actuality of participation; a gesture moving in two (or more) directions: an insistence upon acknowledgment – not recognition, but visibility, optics – being seen; in turn rejecting the simplistic strategies and tropes of identity politics; exiles on Main Street and their own street. (There’s something almost proto-punk about it, too; but Asco was sui generis. To find anything comparable in the art world of that time, one would have to look to the San Francisco Bay area, New York – or the world.)

There was an elegance to the gesture, the execution – sometimes self-consciously deliberated. It wasn’t just about pushing back, but pushing away. ‘Asco’ implies that you purge, eliminate and move on. This was about the next thing. Almost all of these manifestations – actions, happenings, the ‘no-films’ – were visually compelling, photogenic, many set up explicitly for photo-documentation, performed as if to be committed to film forever; but on another level, they were just a palimpsest for the next thing to follow. (Not just the ‘instant mural’, but the anti-mural – the intra- and inter-mural – to be inscribed and reinscribed.)

LACMA’s Pacific Standard Time exhibition on ASCO – “The Elite of the Obscure” – underscored that willful agency, their independence, but also a more ambiguous space located somewhere between an abstracted unattainability and the abject. (I’m thinking now of a conversation Arthur Jafa had with Hamza Walker that touches on his notion of the ‘sublime abject.’ (See, the Made In L.A. 2016 catalogue.) There’s an element of that in the ASCO project.) Amelia Jones contributed a more discursive and very insightful essay to the LACMA ASCO exhibition catalogue that covers a number of issues related to this ‘borderland’ (the term I think she uses) domain.

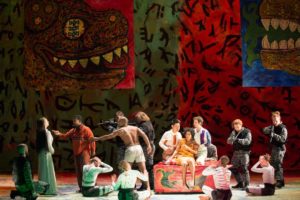

There’s also a ‘hidden-in-plain-view’ aspect to this ‘obscurity,’ this ‘shadowland’ or ‘border play’; also simply playing with the borders themselves or the notion of borders; crossing, re-crossing and folding them over; recomposing them into a kind of tracery. The essence of the larger gesture is embedded or ‘hidden’ in the constituent elements or details. In his later career, it’s as if all these elements and qualities have been filtered into and fused into his larger paintings and designs. Gronk’s ‘theater of paint’ has become immersive and, not coincidentally, operatic. There’s nothng accidental about his opera collaborations with director Peter Sellars (e.g., Vivaldi’s Griselda, Purcell’s The Indian Queen, or for that matter Osvaldo Golijov’s more ‘straightforward’ Ainadamar, with its multiple muses and flashback structure). Each variously features crossing, overlapping conflicts and blurred character/motivations that bleed into the drama. The ‘masks’ themselves blur and bleed into each other. (The mask of course is another key motive and stage element for Gronk.)

There’s also a ‘hidden-in-plain-view’ aspect to this ‘obscurity,’ this ‘shadowland’ or ‘border play’; also simply playing with the borders themselves or the notion of borders; crossing, re-crossing and folding them over; recomposing them into a kind of tracery. The essence of the larger gesture is embedded or ‘hidden’ in the constituent elements or details. In his later career, it’s as if all these elements and qualities have been filtered into and fused into his larger paintings and designs. Gronk’s ‘theater of paint’ has become immersive and, not coincidentally, operatic. There’s nothng accidental about his opera collaborations with director Peter Sellars (e.g., Vivaldi’s Griselda, Purcell’s The Indian Queen, or for that matter Osvaldo Golijov’s more ‘straightforward’ Ainadamar, with its multiple muses and flashback structure). Each variously features crossing, overlapping conflicts and blurred character/motivations that bleed into the drama. The ‘masks’ themselves blur and bleed into each other. (The mask of course is another key motive and stage element for Gronk.)

Certain figures or motives recur: a hand or fist (or claw – there’s a ‘Giant Claw’ – returning to the 1957 D-movie idée fixe of Gronk’s lexicon – incorporated into one of the Griselda backdrops), a schematic/expressionist man’s head or form (and not infrequently, a hyperthalmic, almost explicitly ‘Picassoid’ head), the eye itself, or a quasi-constructivist flower, a schematic gabled house or bungalow (sometimes reduced to a shape like so many ‘Monopoly’ houses, and which sometimes segue to multiple bold arrows), the schematized torrent or tempest, bones, vessels, a wolf or jackal or cat head (enumerating them, I feel as if I’m returning to that ‘hieroglyphic’ domain of my own childhood encounters with mythology), a serpent or serpentine shape, a bird silhouette so streamlined that it’s practically a character (and abstract, feathery lines that reinforce this notion of flight) – all folded and multiplied into a mesh of Twombly-esque graffiti and abstracted shapes. And then there’s the recurring avatar of ‘Tormenta’ herself, in classic black, plunging backline, robe longue and evening gloves, always turned away from us (upstage, walking off, or simply on), her gaze on a horizon line we never clearly discern; or even simply Tormenta’s back – that schematic delineation of spine and musculature framed by that classic ‘V’-line (which carries its own quasi-sexual implications).

There’s a rhythm to this mesh (too loose to be called a grid) of ideograms, silhouettes and graffiti, fitting for an opera set – but it’s open to rhyming: the viewer is free to compose his/her own music to it. I loved that Gronk inserted multiples of the Tormenta icon into the Ainadamar set – obvious reference to Lorca’s muse, Margarita Xirgu; but also Lorca himself, the multiplicity of character/personae, muses, ghosts he held within himself. (Tormenta is a secret sharer always threatening disclosure.) The fragmentary, ideogrammatic quality of these images is also not accidental. It’s the painterly (and theatrical) equivalent of the hypnotic suggestion. At the opera, the orchestral (or actual) backdrop is no less important than the aria. This is the aria we have yet to sing – the unseen horizon line Tormenta will never lead us to – composed out of the mesh of memory and suggestion and the rhythms and rhymes that texture and punctuate our lives. Nor is it incidental that Gronk carries this ideogrammatic, fragmentary approach into his daily studio practice. Gronk frequently begins his day in the studio with a coffeeshop coffee or espresso, the cup or cardboard container for which becomes the surface of his first drawing, figure, expression of the day. Even the insulating sleeve becomes a surface for expressive play – wakening libation becoming the vessel of awakening: Let us begin.

There’s a rhythm to this mesh (too loose to be called a grid) of ideograms, silhouettes and graffiti, fitting for an opera set – but it’s open to rhyming: the viewer is free to compose his/her own music to it. I loved that Gronk inserted multiples of the Tormenta icon into the Ainadamar set – obvious reference to Lorca’s muse, Margarita Xirgu; but also Lorca himself, the multiplicity of character/personae, muses, ghosts he held within himself. (Tormenta is a secret sharer always threatening disclosure.) The fragmentary, ideogrammatic quality of these images is also not accidental. It’s the painterly (and theatrical) equivalent of the hypnotic suggestion. At the opera, the orchestral (or actual) backdrop is no less important than the aria. This is the aria we have yet to sing – the unseen horizon line Tormenta will never lead us to – composed out of the mesh of memory and suggestion and the rhythms and rhymes that texture and punctuate our lives. Nor is it incidental that Gronk carries this ideogrammatic, fragmentary approach into his daily studio practice. Gronk frequently begins his day in the studio with a coffeeshop coffee or espresso, the cup or cardboard container for which becomes the surface of his first drawing, figure, expression of the day. Even the insulating sleeve becomes a surface for expressive play – wakening libation becoming the vessel of awakening: Let us begin.