Egan Frantz’s show, “The Oat Paintings,” provides a possible opening into a discussion of the nature of political art: how we distinguish it from among the myriad latent political aspects of most other art; how we recognize and define its characteristics; how it succeeds or fails on a political level, and the extent to which its formal characteristics can supersede its political content. In other words, can a work of art be deemed successful if it fails to deliver on its stated (through text or title) political intent?

As with most such impossible questions, the answer is an infuriating “maybe.” Frantz reportedly reworked his show of paintings in the wake of the presidential election; and his anger certainly comes across in some of the titles and, in a few instances, in the works themselves. Frantz is essentially a conceptualist and has worked in media more conducive to political expression (mostly Dada-inspired sculpture of the assisted readymade variety). As with Dada, successful political art tends towards a disruptive model. It’s hard to characterize these works as such—though the execution of this mixed-media gestural abstraction encompasses an externalized expression of interior vitriol. More specifically, the artist has urinated over some portions of the painted (copper on canvas) surfaces to produce an oxidation effect. In addition to the eponymous oats scattered generously over the surfaces, vinegar adds an additional solvent effect.

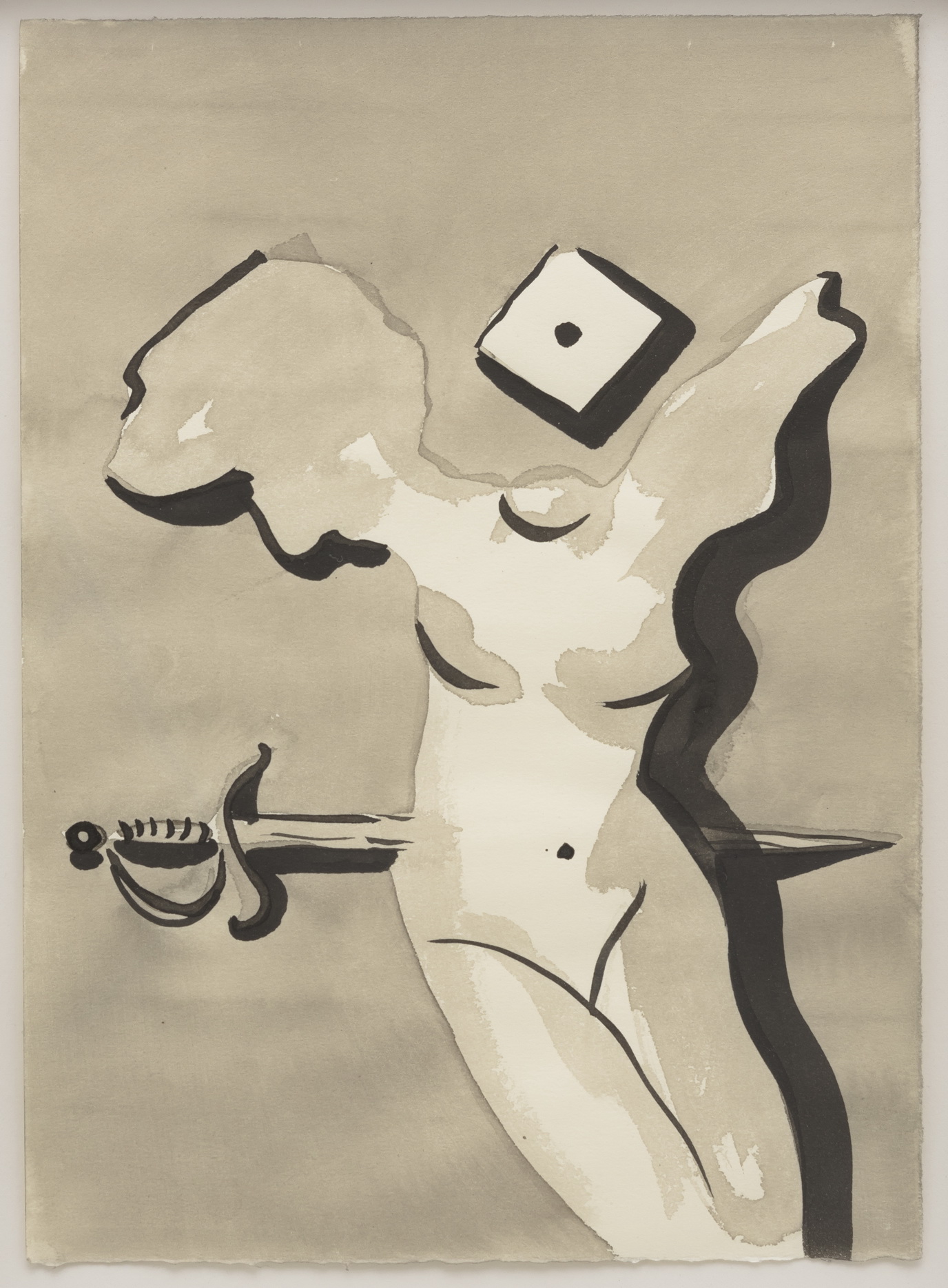

Egan Frantz, NO TITLE, 2016, ©Egan Frantz, courtesy of Roberts & Tilton Gallery, Culver City, CA.

Frantz complicates the “performance” by variously subdividing the surfaces, either with emphatic black or white verticals or framing them within black or white perimeter borders. In TIME (all works 2016), the red border frame is effectively made part of the subject. Within those distinctly demarcated zones, there is some degree of painterly struggle. The paintings are fairly dense chromatically and by virtue of sheer layering, though the solvent effects of “piss and vinegar” render them nearly transparent. Frantz references the Dada legacy with his Nude Descending a Staircase, though his nude might be said to wrestle with its shroud. With its ebullient pale blue and phosphorescent chartreuse zones, Starry Night evoked a subaquatic midnight; and if you met the artist halfway, you might have inferred some fragment of a swastika in No Matter How I Try, I Cannot Discern a Swastika behind a stolid black bar.

Dada references to one side, this is not political work, though. However technically impressive or chromatically vibrant (Frantz’ forebears are clearly Kline and Frankenthaler), whatever anger might have motivated these paintings, it won’t provoke Donald Trump or his ilk, and it doesn’t reach the viewer either.

In an adjoining gallery, however “sinking” the imagery, the mood is buoyant. In Michael Dopp’s suite of pen-and-ink drawings, Capriccio (2016), classical ruins or Baroque follies (and swizzle sticks) float in spherical tumblers or old-fashioned glasses. The gallery’s press release draws comparison to Hubert Robert, but the only real similarity is a kind of luxe and calme. A surreal charm prevails throughout. The real influence here is Cocteau, and Dopp demonstrates a similarly insouciant mastery.