“We’ll play to 700?” John Tottenham asks, but really it’s more of a demand than a question. It’s my second week of trying to combine an interview with him on his drawings of the Manson girls (as he insists, “You don’t have to focus on that series”) and our weekly game of gin rummy. This week there are too many people in the bar and we have to wait half an hour standing around, something that both of us vocally despise.

Each meeting functions like clockwork—we complain if we don’t get our regular waitresses, he whinges over not feeling well for some toothache or heartache, we order identical drinks, and he goes to the bar to fetch a handful of paper napkins, one of which is used for scorekeeping. The rest of the napkins John uses to hastily draw portraits of women’s faces; half-distracted as he watches me shuffle cards or listens to me gripe about some insufficient lover.

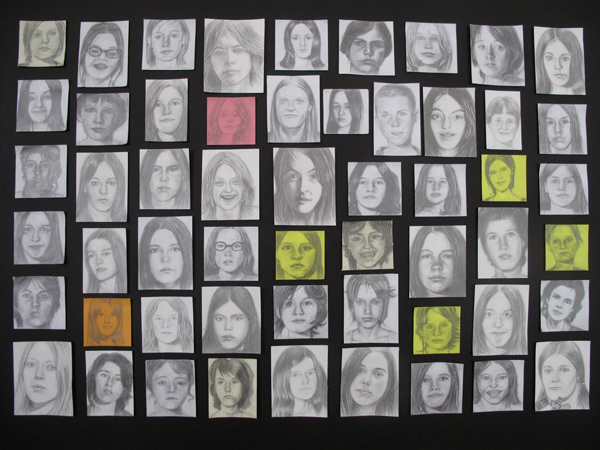

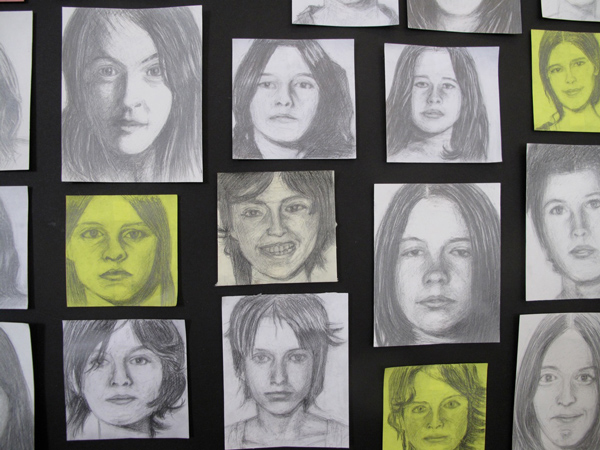

John Tottenham, The Undesirables, 2014, 65 pencil drawings on paper, 32 x 43 in. (detail)

John’s bar-napkin sketches remind me of his portraits of the teenage girls involved in the Manson murders. He insists that the Manson portraits are markedly different, as they took much more work, and involve more erasing than actual drawing. It’s not the technique that’s similar though, but the way he so effortlessly captures the likeness of his subjects.

Another striking feature about both the napkin sketches and the portraits are their subtle and implied sexuality. I ask John if he drew the Manson teenagers because deep down he wanted to fuck them. He answers no, but that maybe he could have. But John admits, “I projected most of my adolescent romantic longing onto them, though there was a lot to go around.”

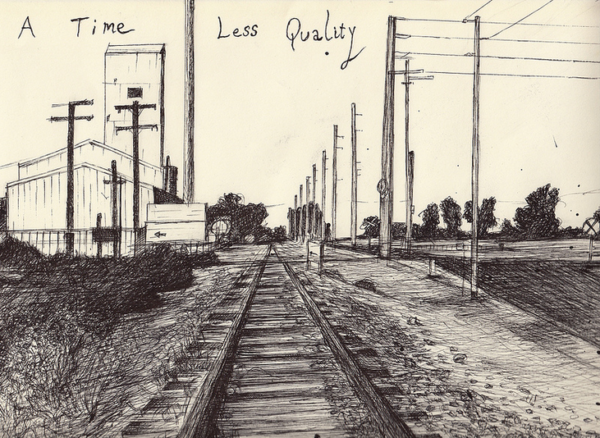

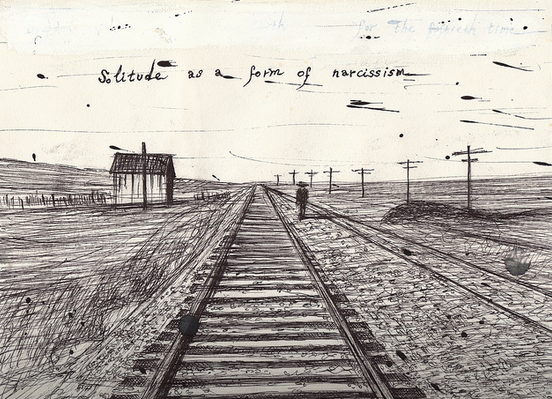

Emptyscapes

John doesn’t only do portraiture, he also draws landscapes or as he calls them, “emptyscapes.” They are usually more tightly rendered and illustrated in pen or ink, and depict dilapidated small towns in the west. “I tend to find myself in those types of places,” he says. The compositions are all the same—a landscape of “timeless decay” with a line of text on the bottom. “They began as an afterthought and someone told me to write on them, so I did.” When I ask if he draws the images from memory or photographs, he answers in his quintessential self-deprecating style, “I don’t have imagination, spontaneity, or memory, and what I just said wasn’t spontaneous either.”

If I say something especially clever while playing cards, I know so because John takes out his little black notebook where he keeps his repository of quips and writes it down. That’s where he gets his lapidary one-liners that turn his haunting depictions of the emptiness of small towns into the poignant antithesis of those awful motivational posters you see in a guidance counselor’s office: “Kill off your expectations and settle in.” It only makes sense that John’s work includes text, as he is a published poet and author of such melancholic titles as The Inertia Variations and Antiepithalamia & Other Poems of Regret and Resentment.

Emptyscapes

I beat him in the next hand, 80 to minus 40, and he admits that he doesn’t feel like a real artist. We are on our second drink, but it’s a screwdriver not a greyhound because the bar ran out of grapefruit juice. “I am an academic primitive, an educated outsider, I went to the worst art school in England and the only thing I learned is to drink, do drugs, and have sex.” He is disappointed when I tell him that his experience is typical.

John Tottenham is a purist. He tells me he is constantly torn between art and writing, and that he would rather spend his efforts on work that he feels to be filling a void than work that is not singular or adding anything to the conversation. He’s the same in art as in writing, as in gin rummy as in everything else. He reminds me, “Better than sex, gin rummy. You said that once. It says less about the quality of the sex life than the quality of play.”