All indications are that Edmund de Waal is a polymath and a scholar. Deferring his place at Cambridge, he apprenticed himself for two years to study ceramics, then graduated with first class honors. In the ’90s he wrote a searching study on Bernard Leach, a prominent British studio potter, and in 2010 published a best-selling memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes, which traced the journey of 264 Japanese netsuke, wood and ivory carvings, through five generations of his Jewish-heritage family. This book is now the work for which de Waal is most widely known. These facts form a narrative arc of potential triumph or debacle with his new exhibition at Gagosian’s Madison Avenue gallery: Will he maintain his brilliant trajectory, or will this show be the moment he falters in his treasured medium?

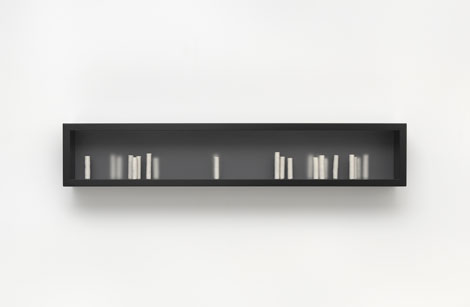

The answer to both propositions is frustratingly both yes and no. De Waal’s show, “Atemwende,” (or “Breathturn,” after a collection by poet Paul Célan) on one hand shows him to be an artist rigorously keeping faith with his studiously gestural approach to ceramics. Here (all works 2013), the medium is porcelain, mostly cylindrical cups, which he impresses with idiosyncratic touches. The main of the exhibit consists of four cases against one wall shelving small clusters of the cups (breathturn I-IV). Other stand-alone cases situated opposite (black field and I am their music) contain shadow versions, black and smoky gray cups along with a few saucers. Both the finessing of the materials and their arrangement create a tender visual tension. The cups in breathturn vary in hue, from white, to bone, to celadon, to parchment. They vary in height and shape, and some gleam with glaze veneer while others are left paler orphans. The smaller collections of obsidian cups and saucers dramatically oppose the lighter shapes. De Waal has made these objects gently suggestive of personality. Each cup recalls a body, unique in its abject indentations, lopsided lips, contorted curves. In their small groups they seem actually huddled together.

Yet, on the other hand, the work evades de Waal’s intensely curious intellect, instead appearing as objects vicariously generated by a Svengali profiteer whispering in his ear: “Let’s make you look more upmarket. I’ve got exactly the right gallery for you to enhance your brand.” The work presented here feels depersonalized and overly precious. It reminds me of Damien Hirst’s pill cabinets: ostensibly about human fragility, but on examination about turning the underlying supports of our precarious, ungainly lives into pretty, modernist objects to be habitually consumed.

The gallery’s press release claims this work confronts “intimate craftsmanship with the scale and sequence of minimalist art.” No, the intimacy is overwhelmed by the commercial sheen of a modernist look that uses the strategy of repetition not to add meaning but perceived value for the price. A docent approaches me as I take notes to tell me one of the cases just sold for $450,000. Of course it did. This show is exemplary of smug modernist opportunism in that it not only makes lovely work generic—it also misrepresents an artist’s singular spirit.