For Melissa Joseph, all things relate to edges. Her practice exists on several of them: painting, felting, craft, utility, art … the list continues. She works in a unique dry-felting medium to create imagery based on her own photography and that of her family. While channeling “ancestral stories,” as she explains, she also addresses broader social issues, including gendered labor and identity. She constantly considers multiple things at once from a perspective that is inherently plural, evolving and defined by many identities: artist, teacher, woman, South Asian, American, friend, daughter and sister. As she prepares for her fall solo show, “Irish Exit,” at Margot Samel in New York, Joseph welcomes me into her studio to discuss how these identities and concerns inform her practice.

While she studied art after teaching and working for several years, Joseph only began using felt in 2020, when she first saw an artist working with the material. Intrigued, she signed up for a class, but it was canceled at the onset of the pandemic. With a degree in textile design, but never having seen—let alone studied—felting, she was determined to learn about it. She scoured YouTube and tracked down other artists online for support. She was innately drawn to the discipline and borrowed from the languages of painting and soft sculptural bas-relief to find her voice.

Joseph insists there is no difference between felt and painting. She uses the same language and concepts of perspective to build her compositions. She begins with a support of industrial wool, not unlike a canvas, and adds layers of colorful wool fibers. She then uses a needle-like tool to poke the wool into the surface, filling in additional details as she crafts the image.

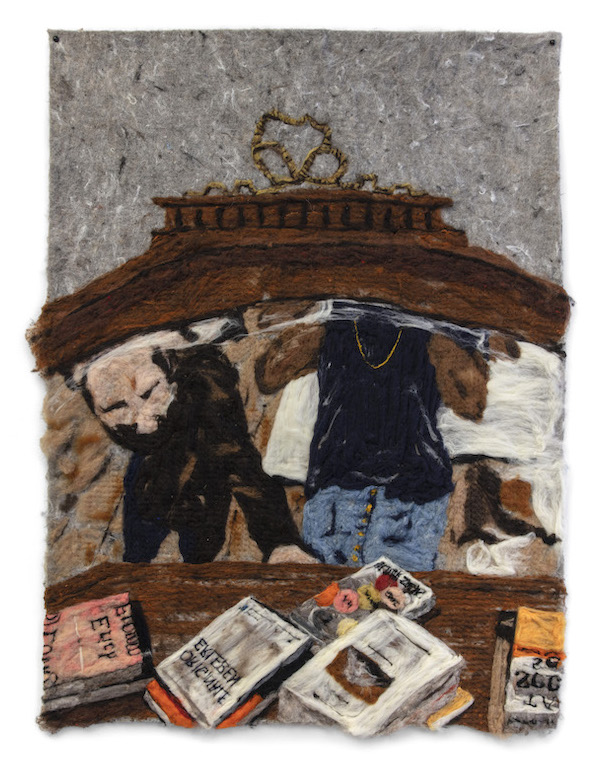

Owen, 2023.

As Joseph explores felting more deeply, she connects with the legacy of craft—noting that some of our most ancient artifacts are craft, and embraces its significance as a marker of changes in taste. She rejects negative connotations of the term in the Western art market. “I deeply respect craft, craftsmanship and craftspeople,” she says. “The art world—specifically the market—has a problem with craft because it’s difficult to value unfamiliar materials and non-Western aesthetics. When I say unfamiliar, I mean materials associated with women and people of color. I waste so much time talking about craft versus art that could be better used interrogating ideas of form and language.”

Now that she excels at felting, Joseph is constantly looking for ways to build on historical precedents and incorporate new techniques, sometimes pairing felted imagery with clay that she’s painted on or with found objects—such items as rusted anchors, first-aid kits and unidentifiable steel shapes fill her studio. Furniture also features prominently in “Irish Exit,” both in content and materials. In A Bow for Angelik (2023), for example, Joseph and a friend are seen in a felted image of a mirror and French dresser. She found a similar, physical dresser that will become part of another piece with a felted painting in place of the mirror. In another work—What Chair? (2023)—the artist’s niece is portrayed lying on the floor with a chair on her chest, playfully subverting its function.

Aunty Loretta, 2023.

Joseph’s use of diverse materials parallels the pluralities we embody. “Because I am biracial, I have to understand pluralities on a regular basis,” she explains. “Over time, I realized this is about more than just race. It’s the idea that we are multiple selves that we constantly try to understand while accepting that this is a fluid definition.”

While at times her subjects are personal and address social concerns, Joseph allows for broad interpretations. Recently, she started taking photos specifically to turn them into artworks. One goal that remains a priority is depicting people who reflect a nuanced, diverse population: “Growing up, I didn’t see images that represented my personal experience; I only ever saw half or none of it,” she says. “It’s insidious and it’s hard to understand the impact this has on one’s self-worth. The opportunity to help increase visibility of mixed-race and South Asian families is not something I take lightly.”

As she works to increase visibility and innovate felting, Joseph’s practice is grounded solidly in the future of craft. The art world, it seems, is slowly following suit. Her work is entering museum collections and is on view at exhibitions across the country. While there is work to be done, artists like Joseph are shifting the visual makeup of institutions. The further the edges are pushed, the sooner the hierarchy among aesthetics and disciplines will finally be understood as antiquated.