Your cart is currently empty!

Ed Moses

In the city of the dubious “angel” we all embrace our icons, whether dead or alive, real or imagined. And if not all the time, then certainly when they deliver to us a newly birthed, risky body of work. Ed Moses has done just that with “New Works: The Crackle Paintings” at Patrick Painter, and while the paintings do at times alternately bristle and breathe, fissure and reattach, ultimately the visual trope is played out as though Moses’ central motivation for creating these strangely static works was decorative rather than, as per his usual aesthetic, aggressively and gloriously experimental. Still, many of the paintings do manage to catapult out at the viewer, only to draw back in again as though one were witnessing a sudden explosion and the inevitable settling of sediment.

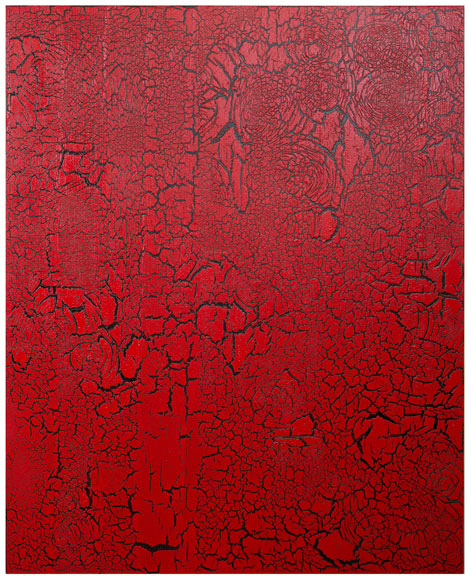

The paintings in this exhibition emphasize a sweeping color palette from ominous, lusterless blacks to voluptuous pinks and vibrant golds. Moses utilizes his crackle methodology as a means of breaking up the picture plane, separating the background color from the more aggressive gestural embellishments that are overlaid to comprise the central imagery. His instincts are for the most part sincere; however, works like White Over Black (all works 2012) run the risk of falling short of high art, only to be reclassified as decorative tableau painting, or in league with a shabby chic mentality. Other paintings have more evident pulse and vitality.

In a recent interview, Moses admitted that the process by which these images came into being was partially an accident. The swirling, spiraling effect found in many of these images had its inception in a mishap where Moses tripped, and falling onto the canvas, created an impression with his elbow, which he then recognized as a discovery within the work. Many of the paintings in the exhibition, including Black Over Bronze, contain this circular gesture, and these are by far the most successful works. The impetus for movement appears more organic and fully realized as the bronze underpainting takes on the effect of skin, breaking open and peeling away, revealing a more violent undercurrent. The same is true of Red Over Black where the colors appear more stylized and far less decorative, as if the relationship between the two shades and the shapes they create is somehow necessary, even inevitable. The suggestion of some kind of obsessive violence exists, or perhaps an awareness of mortality, the crumbling and falling away of the physical body. Regardless, these swirling, intoxicating shapes seem vital and all of a piece.

The more brightly colored images—the electric pinks and greens—appear less convincing, perhaps due to the fact these colors bring to mind a psychedelic mind warp or Easter bunnies, or rolling hills of plastic grass. The best work in this show is grounded in the body—sanguine reds and ominous blacks. Moses obviously has a love affair with the color red, and this unbridled obsession gives the work its breadth, power and distinction.