This show at Wonzimer Gallery, organized by contributing artist Marcie Begleiter, is inspired by the Voynich Manuscript, a work that constitutes a parallel exhibition to the show she curated. The Voynich is a mysterious codex from around the year 1410 by an unknown author—possibly an Italian, possibly a woman,—whose text is written in a script that no one in the past 600 years (including linguists and A.I. bots) has been able to decipher. There is a copy of it in a glass box at the front of the gallery accompanied by a pair of white cotton gloves so that viewers may browse its content.

The intricately mute calligraphy of the text, the strange drawings of unknown herbs, and the unassuming sketches of women (or one woman, repeated) bathing in flower-like vessels and botanical funnels are inscrutable and yet galvanizing. The scope of the manuscript and the language used to write it appear to be fully developed and mature so the viewer is left to surmise that the author was addressing an audience who understood this language and the logic of the illustrations accompanying the text. Yet you will never know who they were, what they understood, or how they, or the author, escaped the historical record. This not-knowing becomes the strange attractor and unexpected content of the work.

The works in the gallery were selected because Begleiter saw in them “echoes” of the Voynich manuscript, which has drawn a consistent and growing audience in the six centuries since its creation. One aspect of the echo is the magnetic power of the code in the withholding of its contents. The other is that of the artist inventing scientific systems on the fly to resolve and articulate its mysterious ideas.

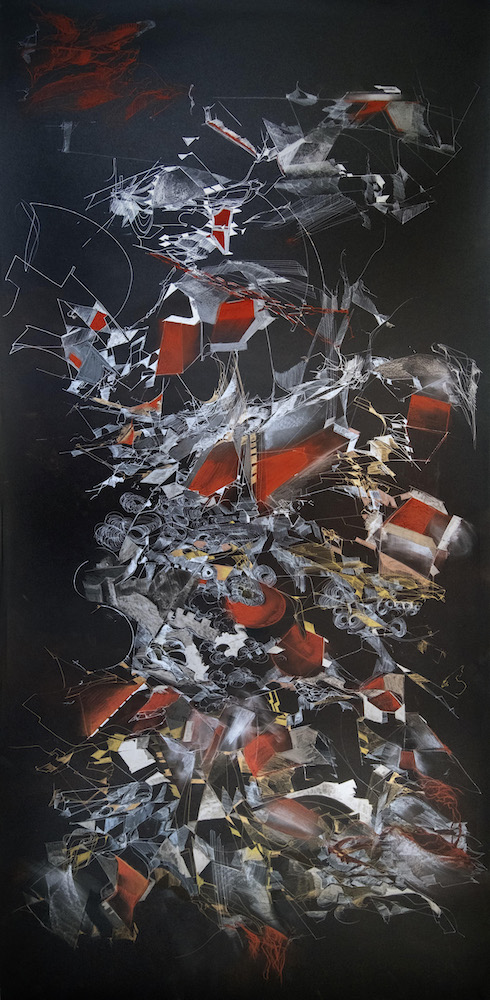

We are told that Linnéa Spransy’s intricate abstract paintings are inspired by ancient spiritual texts but not how the translation of spiritual phenomena by the artist emerges on the canvas in what appear to be scientifically crystallized forms, occurring in both rhythmic and fractured geometric patterns. She accomplishes this in an iterative sequence governed by her own set of rules.

Christina McPhee says her drawings are “made as a site for figuring out the incommensurate and infinitely parsed movements in vision.” I’ve no doubt that she knows what this means, but it doesn’t give away how she arrives at her delicate, intelligent skeins of line, algebraic figures and shaped textures, nor clarify what appears to be the mapping of a mass of green organic matter onto a tangle of blood-red smoke. Those are the secrets of her practice, amping up the intrigue of her method.

There are many other works in the show that are powerful in what they conceal, and then there are some that read clearly enough without code while still inventing compelling new systems. We can parse the construction of Blue McRight’s steel ocean buoy linked to inverted funnels made of fishing nets and grasp their creator’s intention, because the catalog tells us they are comments on the detritus-filled ocean. No mystery there. Begleiter’s own work invents imagined “future” flowers determined by a system that delivers a mutant, uncomfortable shock. These pieces are interesting for a different reason, mainly that the anthropocene is upon us and this is but the beginning. The facts are out there, but there are mysteries beneath them you’ll likely never know.