So I was making the usual—you know: one part cherry juice, one part club soda, two parts peach juice—and thinking about how artists are eccentric. Balzac supposedly drank 50 cups of coffee a day, Grant Wood replaced his door with a coffin lid, and Paolo Uccello would jabber on about perspective when his wife told him to come to bed.

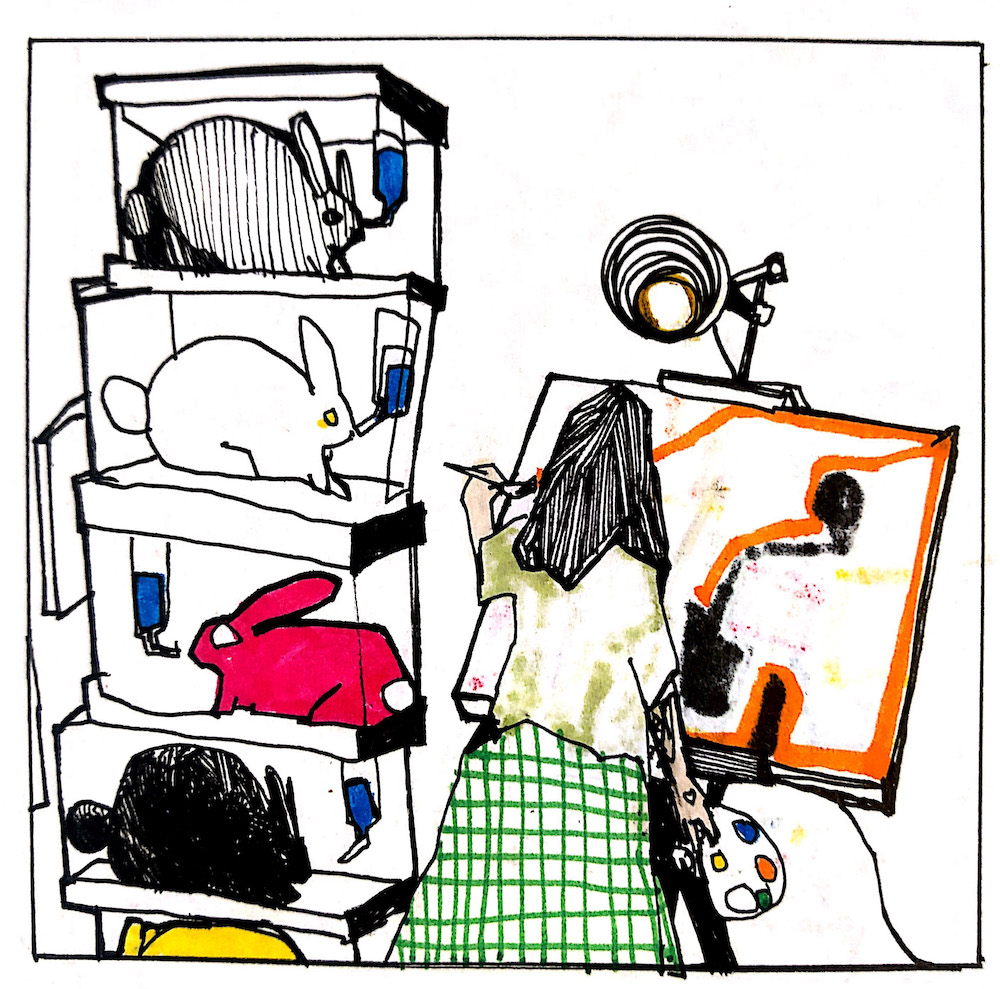

Artists’ assistants, art dealers and nieces who move in after strokes and ladder accidents all report that artists are weird and ask them to do weird things. This is true: I know multiple people who kept fat rabbits and they were all artists.

But y’know what? If someone asks me about my cherry-peach homemade soda I tell them how I spent two weeks vomiting because of whatever I was eating or drinking and then so my friend was like “Here, look, you need to be drinking more cherry juice and peach juice because of your blood type” and I don’t know but, importantly, this friend was hot. And also she was one of the only people I knew who’d got consistently hotter over the decade I’d known her—so I was inclined to take her dietary advice. And now I make this three-bottle drink and I vomit much less. You tell someone that and they don’t shake their head and go “Oh man, you artists!” they go “Oh, shit, that makes sense.” And, really: who doesn’t want to look at a fat rabbit?

You know who else is notoriously eccentric? Rich people. Also children. I don’t actually think the popular theory is true: that rich people are all pretentious and think they’re artists and artists are immature and act like children and children are too stupid to act normal—I think there’s a simpler reason we’re all eccentric: we don’t have day jobs.

None of us have to get used to Quizno’s because it’s the only thing to eat that’s walking distance from the office, none of us have to not wear things with Spider-Man on them, none of us come home every night at six far too destroyed to even consider building a birdhouse out of books we already read and didn’t like.

People would like to be eccentric and don’t, by and large, begrudge artists the right to be just that (unless they’re related to us). They would like to have the time and, especially, the freedom—or, freedoms, rather. Children have to beg their parents for so many things but have the freedom of having no responsibility; the rich have the freedom of having no morality; the artists have the freedom of not having to be reliable or productive—at least the way capitalism usually defines these things. Eccentricity does not reveal the eccentric person: it reveals the extent to which everyone is kept in line by their obligations. We all begin multifarious and then are narrowed.

Eccentricity isn’t diversity. Diversity is: everyone belongs! Eccentricity is: No one does! You can’t campaign on eccentricity. Non-cooperation hasn’t got much of a ground game. Yet everyone dreams of not cooperating. That’s why even people who aren’t eccentric like art: it shows them what things would be like if they didn’t have to make sense to other people. Diversity, which capitalism is learning to get along with, is: I belong here in Los Angeles, but also to the hidden and discontinuous community of the Jewish Diaspora. Eccentricity is: I belong here in Los Angeles, but also to the hidden and discontinuous community of people who love the tiny miniature-glass fronted worlds of Joseph Cornell. I have more to talk about with the other citizens of this invisible and polyglot empire than with any other group I might more easily name. We Cornell-ists love small secrets, and the spider-magic of tiny spaces.

Just as every zoo is nothing more than a catalog of ways to survive, the museum is a catalog of ways to be human—of what we’re like when we aren’t obligated to be something for someone. This antelope thing with a butt like a zebra? It had to be that way. This iron disk, tilted at an angle, with the details in copper wire? That is someone’s heart’s desire. This is what’s suppressed by all our surface similarity.