At first glance Dustin Yellin’s sculptures seem to be all about process and accumulation. They are a technical feat created by fusing layers of collaged and painted quarter-inch glass sheets into blocks that weigh thousands of pounds. These three-dimensional works can be seen from all sides and resemble exploded views of Archimboldo paintings, though the image disappears when viewed from the side.

Each work is made from carefully composed striations containing tiny fragments cut from various printed sources. This flotsam of contemporary consumer culture includes images ranging from bottles of soda and jars of Hellmann’s mayonnaise to images from history and art history, toys, cars, plant life, cityscapes, animals, the figure 0 and faces. Yellin makes two types of works: fantastical landscapes and static figures. Sensorium, Aisha’s Meadow Cave and Etruscan Ice Cave (all 2013) feel like aquariums frozen in time, devoid of fish and filled with strange narratives that extend from the present back into history.

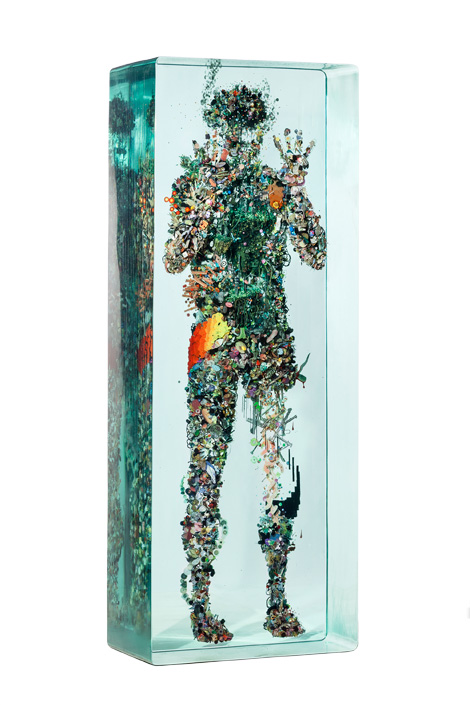

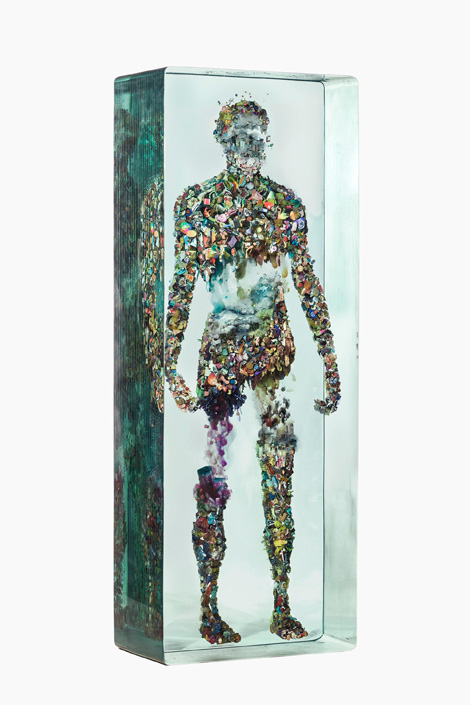

Yellin’s figures stand squarely in their glass cages. While the position of the hands and head may vary, the stance is the same in each sculpture and resembles an anatomical model. The 2014 series of figures is titled “Psychogeography,” after the Situationist term referencing urban wanderings. These are collections of urban detritus found in the street and in the media that, according to Yellin, are “the captured and frozen dynamism of culture.”

In Psychogeography 43, the figure pushes his hands against the glass. In Psychogeography 45, he has a mechanical hook-like hand made out of red paint and a head that morphs into an array of painted dots as it moves from side to side. Psychogeography 38 looks as if it was created by overlaying multiple fingerprints to outline a ghost-like figure. The well-formed body in Psychogeography 41 is almost complete, with only thighs, mid-section and face missing parts. Here the cut-outs are more diffuse, revealing isolated cityscapes made of printed images of skyscrapers. Only a trace of the figure remains in Psychogeography 8, caught in swirls of paint, resembling an explosion.

Yellin’s complex cabinets of wonder, or densely packed terrariums, contain dystopic and utopic moments of imaginary worlds. Impossible to take in all at once, the works are a feast for the eyes. Each glance reveals more and more, like a treasure map unfurling in a never-ending route to the gold.

Yellin’s process is awe-inspiring, and the fabrication of his sculptures attests to his skills and patience. However, the works remain enigmas. The viewer’s reward could be witnessing a portrait of contemporary society and a critique of its influence on mankind; yet, like Marco Brambilla’s time-based montages of Hollywood film clips, Yellin’s sculptures, carefully orchestrated, offer little commentary on his source material or contemporary culture. They allude to the fact that man is trapped, made of infinite parts, a collection of fragments, and is on display, but do not offer interpretation. Yellin’s attitude toward the work is celebratory; he is more attached to the intricacies of their make-up than what they say about the world from which their content is derived.