Duelling Reviews

DUELLING REVIEWS: MARILYN MINTER at Regen Projects

Marilyn Minter’s work begins with the production of the image, taking the elements of commercial photography and twisting up the dials: More saturation. More sparkle. Closer zooms on the irresistible vulgarities of feminine ornamentation. More lipstick. More glitter. While turning down the dial on the demure, the passive, the appeasements to the male gaze, the artist maintains the essential qualities of seduction. In the age-old tradition of leaving certain details to the imagination, for example, misty glass obscures the subject like a veil. The only visible element may be the intensity of the subject’s gaze, or the tip of her tongue as it makes contact with the glass. The painting as a physical object then matches the lusciousness of the image, using enamel paint applied with a brush or the fingertip to achieve what would’ve been much easier to print. She pushes forward traditions of photorealism by recreating the luminous gloss of a digital photograph. Everything is juicy. Every surface appears wet.

In Minter’s best work, the sum of these elements is an erotic radiance, where the tension of voyeurism roils alongside the illusion of intimacy. The work embraces the pleasures of beauty as it subverts conventional depictions of the feminine body and the physical qualities of a painting; it’s a practice about sex appeal and the unexpected ways to achieve it. So if we think of a work of art’s success or failure as the difference between the artist’s intentions and what they ultimately achieve, what’s immediately clear in Minter’s latest at Regen Projects is a deficit: a lack of tension, realism, or subversion. Where we’re promised intimacy, we’re given a sense of estrangement through every level of production—between artist and subject in the creation of the image, then between artist and material as the image is translated into painting.

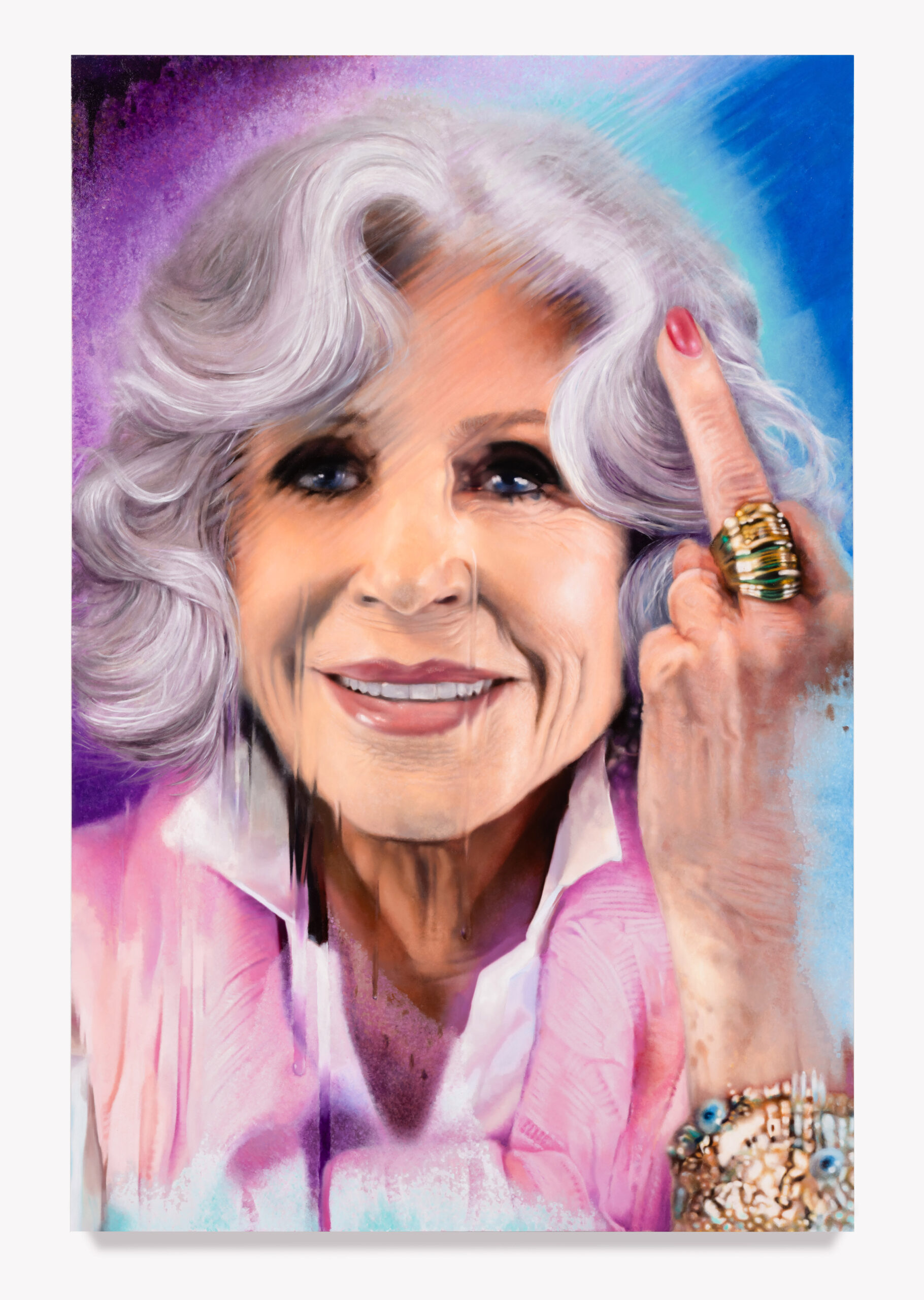

At the Regen Projects show, a row of new portraits of Nick Cave, Jane Fonda, Cindy Sherman, and Jeff Koons present inert smiles on unobscured faces, hallmarks of the perfectly conventional celebrity headshot. Nothing looks wet. Streaks of water on the glass read more as wrinkles on a sheet of plastic film, as if Cave’s smiling face were trapped on the wrong side of Saran Wrap. Minter’s consensual brand of voyeurism captures a subject at ease and in motion: an exhale from parted lips; skin dripping with water or dripping with diamonds.

Rather than dynamism, Lizzo’s and Padma Lakshmi’s unconvincing poses in Minter’s Odalisque series evoke stillness. Lizzo is pretending to look at her phone. Lakshmi is pretending to eat an orange, holding it static against her lips. Where seduction relies on conviction, the lack of ease in their faces and postures shatters the illusion of total agency, seemingly due to the photographer’s failure to disarm or animate her subject. (And we know that Minter is capable; a high point of her practice is her 2007 Pamela Anderson series, where the sublime pleasure on the subject’s face has its own gravitational pull.)

The show as a whole lacks both lust and luster: The overall colors are muted rather than saturated, with no photorealism in rendering or finish. From painting to painting, certain finishes are even more powdery and less lustrous than others. All artists of Minter’s stature rely on the work of assistants, but these inconsistencies read less as the product of choice than managerial negligence.

I do like the After Guston images conceptually, thinking of Minter as another film director rebooting an already beloved franchise. In her version, iconic red MAGA caps replace the Klansmen in Guston’s most celebrated scenes, smoking cigarettes and piling into a getaway car. Some images dabble pleasantly with absurdity, disembodying pairs of googly eyes and anthropomorphizing lipstick-stained cigarette butts. But the execution itself is a bit unremarkable, more poster than painting. The undeniable fact about this particular body of work is that it’s lost its gloss.

Marilyn Minter’s half-century oeuvre has maintained its focus on notable, and notably inflammatory, subjects for nearly that long. And for almost that long, her subject matter has at least partly eluded most of us. Sex is all over Minter’s glistening, lascivious imagery—but her art is not “about” sex. Her pictures brim with signifiers of her gender, both corporeal and commercial, but that’s not what makes them feminist. The dynamics of consumerism, bringing forth a timely (not to say fashionable) Marxist critique, drive Minter’s argument; the never-ending pas de deux between product and user—death and the maiden, you might call it—either erupts anew or simmers incessantly in every apparition she conjures. The slyness with which she promulgates her cautionary regard actually serves quite effectively to pull us into the politics without subjecting us to moral castigation or virtue signaling. Minter’s peep show delivers a fevered but carefully modulated tour of the mind’s red-light district, albeit one bereft of its denizens who have seemingly left their adornments, suggestive or not, behind.

This is not to blame Minter for a Pop-surrealist bait-and-switch. Her pictorial world is still pretty funky. Eros oozes from even the least of her tableaux, and she makes it easy for any of us to get all hot and bothered over her sensuous close-ups and suggestive still lifes. But for all their dirty secrets, the still lifes, and indeed the body parts, serve as memento mori, cautionary excesses in the Spanish and Dutch traditions that prescribe sobriety over lust. (Interestingly, Minter’s partial reformulation of still life into landscape, as in the several After Guston (Ashtray) renditions, posits nature itself as the ultimate healing context.) Thoroughly modern Minter, mind you, is not preaching sobriety instead of lust. As she has averred in numerous interviews, she does not begrudge her sisters their kicks; in one sense, her art pays homage to female pleasure without, um, the benefit of male gaze—admitting thereby that consumerism can be a very effective means to pleasure without shame.

But, per Minter, this epicurean indulgence is not without peril. Her audience does not risk danger to body or spirit; her figures, present or absent, do. Who those figures are, or could be, implies that spectators could convert to subjects, that those humanoids bouncing around the After Guston series, or the invisible women whose lips and lotions churn about in various of her pictures, are us. The larger odalisques and portraits run more on fame fumes, their readymade icons including the likes of Jane Fonda and Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons and Padma Lakshmi. They are fairly engulfed by the trappings of their trades, and many may not be recognizable at first to cultural consumers (the consumers most likely to comprise Minter’s audience).

But that’s Minter’s point: Is every culture consumer—or consumer of any type, for that matter—aware of the discourses and objects of desire adjacent to theirs? Does art function today as a means of translating across countries, governments, national myths and delusions, or as a tool for maintaining difference, productively or otherwise? Is consumption simply a means of corporate—or state—control, or can consumers unconsciously or even consciously resist their manipulation by voting with their feet? The inquiry dates back at least to the 1960s, but the new urgency it has taken on even just this year has been stoked by, and now stokes, Minter’s oeuvre. If not a politics of glamour, Minter proposes an inevitably perverse glamorous politics.