Duelling Reviews

DUELLING REVIEWS: BRUCE NAUMAN at LACMA

At LACMA, Bruce Nauman’s For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and finger) (2010) is a large-scale video of two pairs of hands, palms out, holding up—you guessed it— different combinations of their fingers and thumbs. In two separate, simultaneous recordings, Nauman’s voice overwhelms the cavernous gallery with instructions for the left and right hands: “third Finger, second finger, thumb,” and so on, flatly droning on at a steady pace, each recording cacophonously talking over the other. The stark simplicity is not particularly pleasant to behold, but it is strangely hypnotic. Being conceptual art of the highest order—the kind that ordinary people dismiss as pretentious nonsense—For Beginners prompts an immediate question: “Why?”

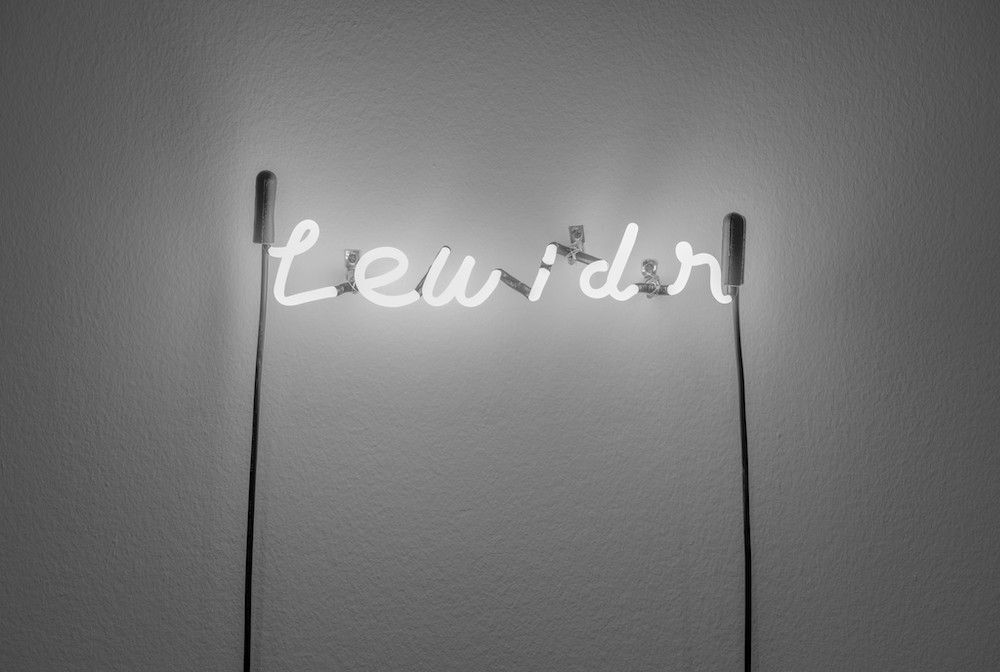

The key to viewing and potentially enjoying a Nauman performance is what improv comedians call “finding the game”—that is, identifying the unspoken logic driving the actions of the scene. Since the 1960s, the precise rules of Nauman’s game have always changed from one piece to the next, but the constant is a philosophical question of language, and how conventions of grammar, pronunciation, meaning, and so on can be inverted, scrapped, and reinvented. Shown alongside For Beginners, Lewidr (1972), is the letters of dealer Nicholas Wilder’s last name rearranged and wrought in neon. The resulting word is nonsense, but likely deeply satisfying for Nauman to pronounce. In both the artist’s performative and plastic works, language serves as a prompt to explore the movement of the body in often absurd or sonically and visually grating ways. Think of it as theater liberated from the constraints of narrative, entertainment, or logic.

Installation photo, “Bruce Nauman: From the Collection,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Aug 31–Oct 13, 2025, © Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, by Jonathan Urba

So, back to For Beginners: Although it’s never explicitly explained within the exhibition, the linguistic foundation of this piece is musical notation, the kind for beginning piano players that numbers each finger. Reading aloud all the possible combinations of fingers and thumb algorithmically produces a choreography for the hands, as well as a kind of song with no musicality. Scott Tennet, LACMA’s former communications chief, points out that recording follows the ¾ time of a waltz: “SECOND fin-ger / THIRD fin-ger / FOURTH fin-ger / THUMB.” Nauman dried out and deconstructed the conventions of musical composition to the point it’s no longer recognizable, down to its mathematical bones. The piece debuted at Sperone Westwater in 2010, alongside For Beginners (instructed piano), a recording of pianist Terry Allen struggling to follow Nauman’s verbal instructions. I haven’t heard it, but I imagine it sounds like the instructions themselves: the cerebral equivalent to banging down on the piano keys.

I recognize the displeasure in being thrown into a game with rules you do not know, by an artist who obviously finds himself very clever. But I would argue that this is the joy of Nauman’s work: Finding the game is unraveling the inner workings of the artist’s imagination until you reach the lucid center. Entertaining madness as a generative force, his work translates the wanderings of a restless mind into physical actions or materials. Never feeling the need to explain himself, he embraces the supreme uselessness of art, and I mean that in a good way. Positioned outside the parameters of the practical or easily understood, Nauman makes his philosophies available for anyone willing to meet him there.

Art critics gladly assume the role of intellectual janitor, and gladly become more patient and accommodating, explaining in smooth, step-by-step essays each institutionalization of the obvious, with the appropriate catechismal tone… —Peter Plagens, “Roughly Ordered Thoughts on the Occasion of the Bruce Nauman Retrospective in Los Angeles”, Artforum, 1973

Even in Tibet the yab-yum images are not intended for general use but are meant to be viewed only by those who have received proper instruction concerning their esoteric significance. —Encyclopedia Britannica, 2025

I do my best to explain Bruce Nauman to the friend I went to LACMA with and then we make our way to the other side of the museum, where, several rooms deep into “Realms of the Dharma: Buddhist Art Across Asia,” I do my best to explain three gilded statuettes of women fucking monsters.

I feel, in both cases, on equally thin ice. When discussing the inner meaning of the work of Bruce Nauman—a man a mere generation or two removed from me, whose friends, colleagues, associates, rivals and enablers I have been one degree of separation max from for my entire professional life—I am as hesitant as when I attempt to explain the deepest arcana of medieval Vajrayana Buddhism.

When I say that the sexual union of these small golden deities—known as yab-yum—represents the union of opposing concepts, I am speaking directly and only from what I book-learned through the ivoriest of ivory-tower channels and deeply unsure whether those in the know—the chain of monks who preserved them in their temples and the artisans responsible—would laugh to hear it the way I laugh when I hear Blondie’s “Rapture” called a “seminal hip hop single.” I feel the same hesitancy around Nauman—I could say he’s playing with language and the body-as-signifier, but I am simply repeating what I’ve read about something essentially inexplicable whose essence is utterly alien. The major difference is that despite my total ignorance, I actually want to look at the weird Buddhist art—and I can look at it for quite some time: the small delicate objects repay extended viewing. I may not be hip to what 15th Century Asia was trying to tell me about enlightenment but I can own, at least, my own reaction: I can see the horned god and his literally dozens of tiny and beautifully sculpted hands with their intricate play of jewelry and mudra, I can be dazzled, declare them, in all earnestness, fascinating. I can like it and describe why I do.

Installation photo, “Bruce Nauman: From the Collection,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Aug 31–Oct 13, 2025, © Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, by Jonathan Urban.

Despite being the outcome of a two-thousand-year tradition of esoteric philosophy and cosmology, the Tibetan images have a reason to exist outside of anyone’s ability to explain or even learn from them, the art of Bruce Nauman does not. Nauman is an artist who simply cannot exist outside the business of contemporary art criticism.

A massive room. A large screen hangs from the ceiling like a taut banner. On it is projected For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and finger) (2010) wherein a voice announces exactly those combinations described in the title while two pairs of white man’s hands, one above and one below, enact them on a divided screen.

It should be emphasized that this film is not in any way experimental. Like his contemporary John Baldessari’s photo series Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts) (1973) and unlike Steve Reich’s “Come Out” (1966) (a sound piece where Reich cuts two parts of a spoken phrase into different audio channels and slowly moves them out of phase) or Georges Perec’s A Void (1969) (a novel composed without the letter “e” or any words which contain it) this piece is not an attempt to see if some new and interesting thing can be generated using a simple procedure. The art is the procedure, and it’s going to be shown whether the result is interesting or not. During fifty continuous years of “exploring the space of the body” Nauman has not once asked whether it was good for you.

At the beginning of his career, he said: “If I was an artist, and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.” Nauman was part of a generation of boomers interested in ideas of what art could be while utterly uninterested in ideas of what good art could be. It was light work, and paid well.

Nauman inevitably comes packaged with ideas about the pomp of art deflated by self-consciously meaningless activity. This only seems to work if you come to the table with the rather guilelessly middlebrow idea that art inherently has dignity, rather than the more tenable idea that art is usually fairly dull and sold-out and starts from a position of having something to prove both to the average and wised-up viewer.

The idea of an organic, visceral response to Nauman’s work—a response which does’t require any familiarity with the critical gymnastics wheeled out to justify it—posits a viewer somehow both unsophisticated enough to still be walking into art galleries at this late date expecting uninterrupted dignity and grandeur and yet sophisticated enough to realize that Nauman’s attempting to undermine that expectation, care that he is undermining it, and enjoy that it is being undermined.

Installation photo, “Bruce Nauman: From the Collection,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Aug 31–Oct 13, 2025, © Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, by Jonathan Urban.

I submit that few such people exist—and for the few that do or did, the fun in seeing art’s supposed balloon burst dissipates after the first few darts. After a while the viewer is no longer looking at or enjoying the work, they are enjoying the fact that they get it—that is, they are where the critical consensus on Nauman always has been: enjoying it because they are enjoying that they belong to the group that understands it. This is probably fun if you’re the kind of person who wants to be smart but is always worried you aren’t.

There is occasionally an allied assertion that there’s “wit” to be found here: A certain kind of viewer identifies with Nauman’s talentless seeking, and sees these diversions as hipster Nauman hilariously at play after sneaking into the marble-fronted doors of the house of art, another kind of viewer sees talentless-but-fortunate hipsters at play as most of what’s already in the house of art and what owns the house of art and what has always owned it and the main obstacle to finding anything worth looking at in it.

I can offer one other concrete observation not received second hand from critics attempting to justify this work: Nauman was a key figure in establishing that Conceptual Art could be expensive to make. It could require neon or a bunch of big taxidermy molds and not be bound to the Arte Povera asceticism of a pile of bricks or a chalk outline on the street, thus freeing the Conceptual from any necessary association with countercultural socioeconomic martyrdom in the name of art. Conceptualism no longer needed to be the product of artists driven to engage with art only on its most essential terms due to being unable to afford traditional materials or tolerate their connotations of luxury, it could also be just any dumb idea with money thrown at it. He is a key link in the chain from Duchamp’s Parisian garbage-heap aesthetic to the more extravagant garbage of Jeff Koons.

Accompanying For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and finger) in its room in the LACMA is a neon Nauman from 1972. It is called, and says, Lewidr in cursive text. The interpreting mind goes to work, scrabbling at this nonword—it’s an anagram of “wilder.” It’s wilder than no known object. Turns out “Wilder” is the name of Nauman’s first art dealer. Tee-hee.

The same year Lewidr was made, the T Rex song “Are You My Main Man?” came out. The lyric might be a reference to—or have inspired—glam-rock manager Tony DeFries, whose company, called MainMan, was also formed that year. It’s also a good song that people who are not boring like to listen to for its entire length because it sounds good. So, the Nauman piece is like that, only less.

Nauman has a logic to what he’s doing. A gnomic, personal, useless, un-generative logic that points at nothing and doesn’t even have the grace to be funny to anyone who is themself funny—but a logic nonetheless. The draw isn’t anything which that logic can lead to but merely the fact that it exists: Can you find it, kids? It’s like doing the London Times crossword puzzle only more expensive and easier. This is art for rule followers: It’s for the kid in the class smart enough to keep putting their hand up, but not smart enough to have anything better to do.