Beatriz Jaramillo has had water on her mind ever since she can remember. The Colombian-born Los Angeles–based artist spent her childhood in what sounds like an idyllic wonderland—wandering around the tropical rainforest that surrounded her family’s home. She remembers playing in the water: “It was magical.” There was a deep connection that came from her family—she has memories of her grandfather, whose house she helped connect a hose to that siphoned water directly from the land. When the artist returned as an adult, however, the area was totally destroyed. “It’s painful,” she says, “My heart hurts every time it’s a new time talking about it.”

This July, people all over the world watched in shock and horror as a fire erupted in the center of the Gulf of Mexico due to a faulty gas pipe. The image of a swirling “eye of fire” seemingly descending to the depths of hell was a keen visual representation of the breaking point we are at, which perhaps accounts for videos of the event going viral. The climate crisis jeopardizes plant, animal and human life in every way on this planet, but possibly at greatest risk is our water.

Our planet is 71% water—be it rivers, lakes, streams, creeks, oceans or seas, and for centuries humans have relied on these waterways for fresh drinking water, food, and as places of recreation. However, more and more rivers, waterways and oceans have been polluted, dammed, re-routed or depleted. The issue of a shrinking suitable water supply is especially relevant for California, where just this year a cease and desist letter was sent to Nestlé (now known as BlueTriton) in San Bernardino, to stop diverting water from communities during what will be another year of drought. Residents and officials are in a fight to keep water from being siphoned from natural environments in a state whose constitution states that all water “belongs” to its citizens.

Beatriz Jaramillo, “In Between: Wetlands In L.A.,” photo by Rubin Diaz.

Jaramillo’s recent work, “In-Between: Wetlands In L.A.” explores the lost wetlands that used to exist—and if fact thrive—in Southern California. Jaramillo, who is a gallery educator at the Norton Simon Museum as well as LACMA, has learned that when people make a personal connection to the work of art, then they are more likely to care about its subject. “So I thought, if I make the work about Los Angeles and they make a personal connection to the land, they will care—they will protect it, they will tend to the needs of that area.”

Her previous works dealt with climate change and both land and water issues on a global scale—her 2018 project, “Broken Ice” explored the melting ice caps. But Jaramillo wanted to bring things back home. Wetlands are something of a gradient, with saltier water of the ocean mixing into fresh water inland. The salt, fresh and brackish water in between give a varied and rich place for a wide variety of species to thrive. Most of the wetlands in Los Angeles are gone—about 95%—and restoration is a rocky and unclear path.

Jaramillo thinks that her duty as an artist is to ask questions, and to reflect and encourage people to be better stewards of the land. Her current project reflects on the contamination of 27,000 barrels of DDT on the California coast near Catalina Island, an amount that scientists called “staggering.” The work is a series of photographs that have been perforated to spell out Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, the chemical name of DDT. The perforations are somewhat obscured by the background—a metaphor for how these toxic pollutants are hidden within our water.

Beatriz Jaramillo, “Broken Ice,” 2018. Photo credit: George Evans.

It is, however, impossible to ignore the political aspects at play when it comes to the climate crisis. Carolina Caycedo, a Colombian artist living in LA, is releasing an upcoming project with her partner artist David de Rozas—commissioned by Ballroom Marfa—titled “The Blessings of the Mystery.” The project is centered around Amistad Dam and “shows that colonialism continues to upend in Texas and the US through the extraction of oil and gas, the construction of the border wall, and the erasure of Indigenous narratives and people who live there and claim their relationship to the land,” says Caycedo.

Caycedo has taken her own role as an artist into account, and what the artist’s role is in both society and in nature. “As artists sometimes we are complicit with these hierarchical or colonial perspectives. We use, for example, landscape as a formal way to view nature as an observer instead of viewing ourselves as part of nature, which we are as humans in the middle of nature,” she says.

Caycedo has been working on “BE DAMMED,” an ongoing project that looks at different case studies and communities across the Americas that are impacted by dams since 2012. The project entails community events, videos, sculptures, photographs, publications and other mixed media. Like Jaramillo, she was influenced by environmental events that occurred in Colombia during her childhood. During adolescence she lived on the banks of the Magdalena River, which flows through the western part of the country. In 2012 she learned they were damming the river and diverting it, which Caycedo found “shocking,” and triggered her interest in the issue. Through a friend, she started a relationship with the community and the people involved with resistance to the dam.

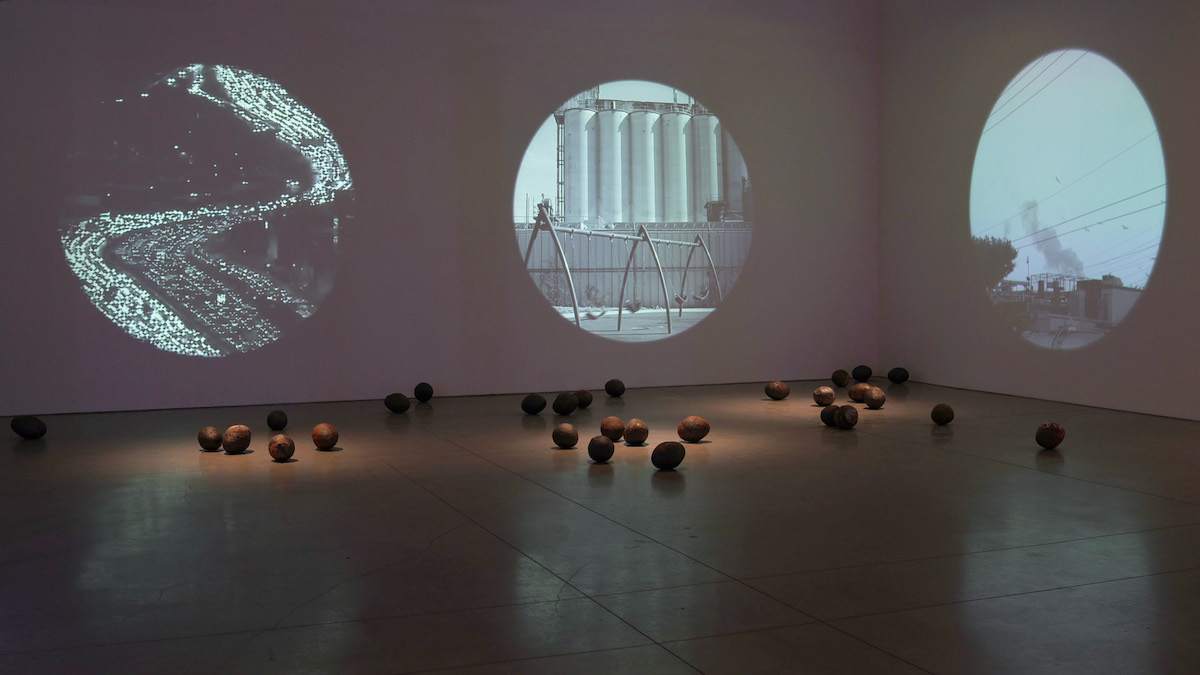

Carolina Caycedo, From the Bottom of the River, installation view, MCA Chicago, Dec 12, 2020–Sep 12, 2021, photo by Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

“It hit my personal history and sparked my interest and it just unfolded. When you start researching and pulling at so many strings, that took me to the next one, and the next one, and I got awakened in an environmental way,” says Caycedo. She became concerned with how extractivism—the process of removing large quantities of natural resources considered valuable for exportation—operates across the Americas, and the privatization of bodies of water. She points out that development, often said to be beneficial for all, frequently alienates communities, including Indigenous, whose resources are at risk of further exploitation.

Caycedo points to exploring non-western epistemologies as a way to address both the climate crisis and solutions to it. From a hierarchical perspective, water is solely a resource for people to use, but is separate from any relationship with humans. Non-western ideas can “understand water instead as say, a relative, as something that sustains life, but understands life as a balanced relationship between the human entity and the water entity with reciprocity.” She proposes humans look even beyond our species to explore different epistemologies—say that of fish or even water itself, to understand our relationship with water and to build knowledge. Caycedo’s project “Water Portraits” (2016) sees rivers as political entities with their own ability to be agents of change, which illustrates this idea.

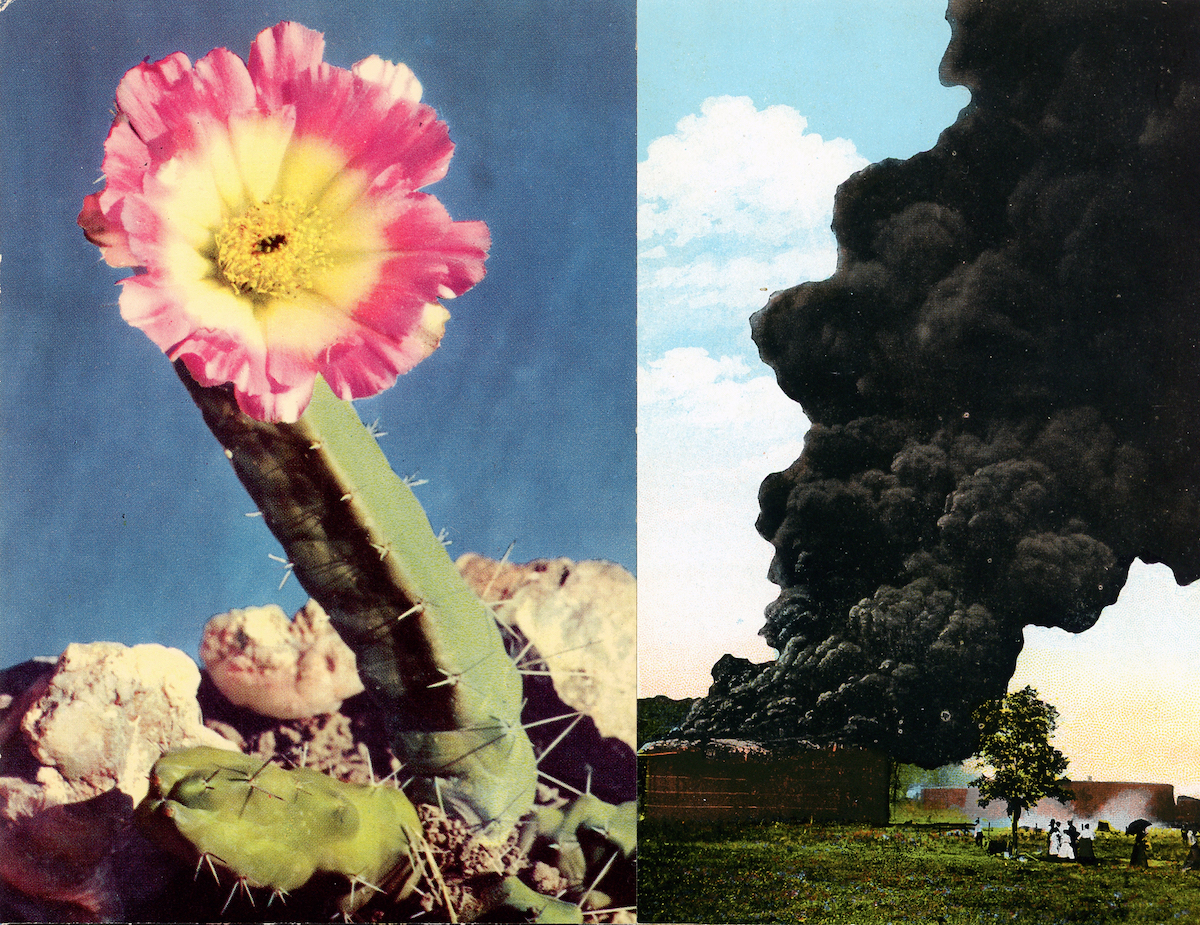

Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas, Bloom Boom (detail), from the “Greetings from West Texas” series, 2020, collage, 6 5/8 x 10 1/2 inches framed, courtesy of the artists, commissioned by Ballroom Marfa.

Caycedo is a firm believer that a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective in addressing the climate crisis and in activism surrounding water rights. While sweeping governmental reform can be helpful, she points to listening to community members, Indigenous voices, and existing community structure to heal climate issues surrounding those communities.

Mexican transdisciplinary artist Maru Garcia also looks to community for guidance and inspiration for her work. However, Garcia approaches climate issues from a unique perspective, as she holds an MS in Biotechnology and a BS in Chemistry along with an MFA in Design & Media Arts. This combination of science and art is evident in the aesthetics of her work—which appear at times like the personal laboratory of an experimental scientist—which, I suppose, they actually are.

Garcia’s project, “Vacuoles: Bioremediating Cultures” (2019) explores the environmental and social crisis brought on by the Exide soil contamination in Vernon, in which a battery recycling plant emitted toxic metal dust and neurotoxic lead into the largely working-class Latino LA neighborhood for decades. The installation included 29 ceramic pieces containing lead-contaminated soil from the site, along with video projections.

Maru García, Vacuoles: Bioremediating Cultures, 2019, installation view, 29 ceramic pieces containing lead-contaminated soil from Southeast Los Angeles, 3-channel video projections, courtesy of the artist.

Garcia’s most recent project is in the works and builds on “Vacuoles” in collaboration with a gallery in South LA, the Getty’s PST and a scientist involved with the Natural History Museum. The science-based environmental and social justice–oriented project will build on previous community relationships and involvement, with a DIY project of actually repairing the soil in the affected areas of the toxic pollutants. “We are developing a method of lead reduction using minerals that people can apply themselves in their own backyards, so they can be more protected while waiting for the cleanup from the government,” says Garcia. The cleanup, she notes, is taking a long time and is also selective about which areas are eligible so, for some, this DIY solution may be the only one available.

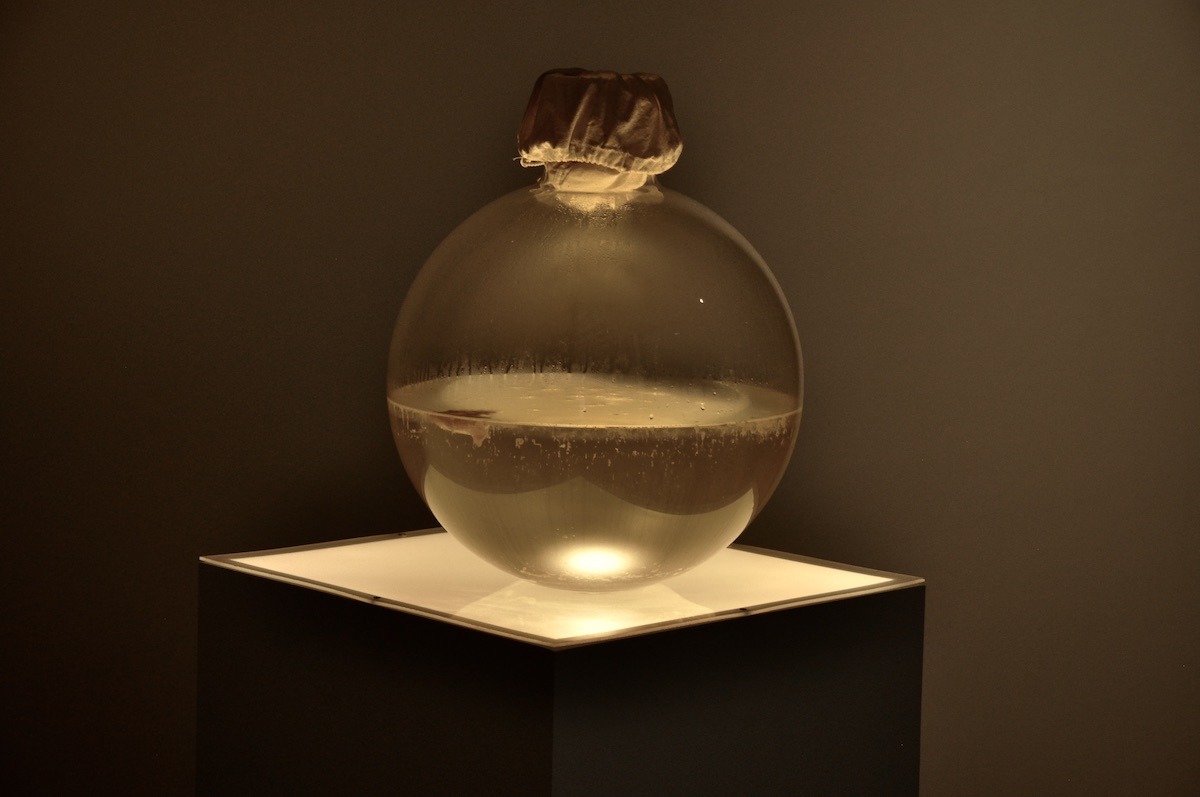

Maru García, “Membrane Tensions” (detail), 2021, Photo: Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery.

The method of getting down to a cellular level spans into another one of Garcia’s projects, “membrane tensions” (2021), which consists of glass containers containing SCOBY kombucha cultures. Garcia aimed to understand humans as part of a family of Earth’s beings, and the origins of human life. The membrane surrounding that cell functions as a limit, but it is permeable and allows for communication. “How can we relate ourselves with the rest of the natural world and think of ourselves as organisms that can have membranes instead of rigid limitations?” asks Garcia.

The piece uses living cultures that have a symbiotic process with water, and is collaborative rather than competitive. The works are testament to evolution due to collaboration, and in many ways Garcia’s approach offers a philosophy of hope. When contemplating contamination and the climate crisis things can seem very daunting, yet the projects bring it back to how we can relate better to our environment and heal ourselves through a symbiotic relationship with the earth. To me, the project sounds like a proposition.

While humans are undoubtedly the cause of the climate crisis and ecological ruin, we can also be stewards and work together to develop solutions to the problems we have caused. By using art, Indigenous practices, community work, governmental pressure, and scientific inquiries, humans can work together for resolution. Humans are as much a part of nature as the ocean, rivers and seas, and through a connection to our place in nature, we can perhaps find ways to heal it.