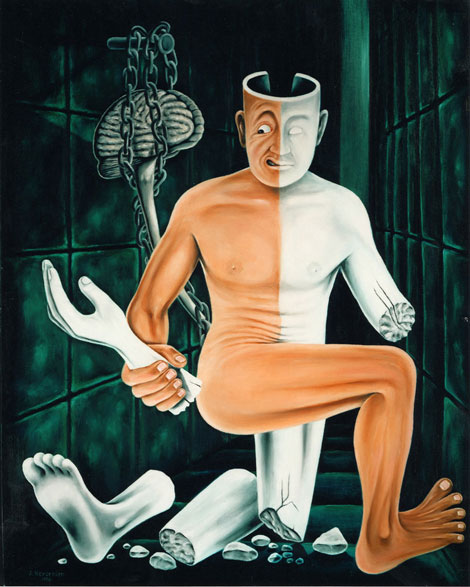

Dr. jack Kevorkian, the infamous “Dr. Death” who passed away in 2011, sits somewhere in the public consciousness between the Unabomber and Mother Theresa depending on whom you talk to. The physician served eight years in Michigan State Prison for second-degree murder (assisted suicide) in 1999, after facilitating the deaths of approximately 130 patients. Gallerie Sparta in Beverly Hills showed 11 of the 18 seldom seen paintings he completed in the ’90s (alongside one of his original “Thanatron” suicide machines) this May. I was just dying to see what the doctor’s canvases looked like, much like I was fascinated to see George W.’s selfie shower painting and John Wayne Gacey’s “Pogo the Clown” series.

Painting since childhood, Kevorkian enrolled in an oil painting class in his 40s. His paintings aren’t awful; in fact, the more I absorbed the works and read his own descriptions on the gallery walls, I gained a real appreciation for the complicated, talented, pissed-off guy using oil on canvas and panel as another way to tell his story. Besides his art, activism and mercy killings, he wrote books, composed and played music and invented things. His controversial ideas about death alienated many colleagues in the medical community decades before he became a media sensation. He was a pessimist, characterizing humanity, in his own words (on placards next to the paintings) as “a miasma of distrust and suspicion,” believing that the god we really worship is Satan whose sovereignty is evidenced by mindless subjects in “Bosnia, Ireland, Pakistan, the Middle East, Rwanda, Kosovo, and—Waco” and presumably, in the Armenian genocide his mother fled as a young woman. His joy in provoking society is evidenced by painting with his own blood (none of the works shown here), his comic/fantasy illustration style, morbid subject matter and works that poke fun at Christianity and religion.

In Coma, death’s skeletal hands in the foreground seem eager to claim the sad comatose figure, the CAT scan tunnel his bed sits in forming the mouth of a giant skull face. Stylistically, these images could easily be crappy tattoos on the skinny arms of some metal-loving teenager in Arkansas. (In fact, the good doctor allowed the metal band Acid Bath to use one of his paintings for their album cover). Only in reading the accompanying text do you understand the doctor’s compassion for his patients and anger over their suffering. His political paintings are more direct, aiming for a Sandow Burke-like punch in the face but falling short. In The Papal State of Michigan, Hitler touches the state’s capitol building, spoofing the Sistine ceiling and calling out the governor as a fascist ruled by religious nutjobs. For all of the visual sarcasm in his allegorical paintings, his portraits (of his beloved parents and his ultimate hero, composer J.S. Bach) are reverent and strangely, compellingly flat. Like a cross between Colonial American paintings and outsider art, they are full of admiration and sweetness with none of his trademark anger or humor.

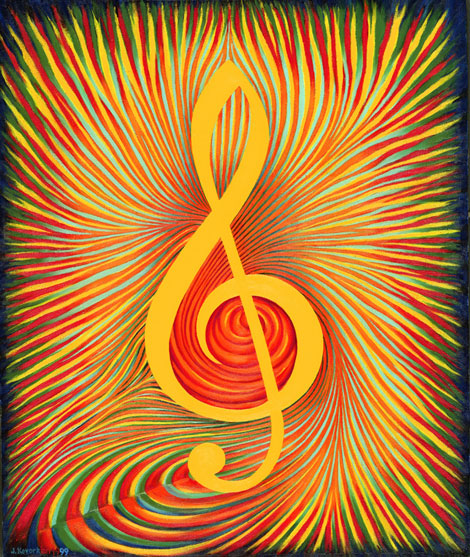

Lastly, his music-inspired canvases are his most abstract and optimistic, yet least interesting. Giant musical notes floating on multicolored surfaces aim to show the patterned order of a classical composition and the jazzy vibrations of sound. Fugue is a poor man’s Stuart Davis while Chromatic Fantasy blends Charles Demuth, pop and psychedelic op art into a strobing mess. But it was music that soothed the doctor through all of his depressing death dealings and these paintings are a tribute to one of his greatest passions.

History rarely rewards the radically forward thinker. Kevorkian wanted people to have the right to plan their own death, with dignity, without having to painfully wither away to nothing. I predict Kevorkian will be on a postage stamp someday. These paintings are the fascinating artifacts of a pioneer.

Images courtesy Gallerie Sparta