Three of the most storied artists in recent Los Angeles history were the subject of “Disappearing—California c. 1970” at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (May 10–Aug 11, 2019), the show’s only venue. Despite the tight focus on just three artists, the exhibition encompassed the breadth of the radical experimentation of conceptual and performance art in Southern California in the ‘70s, a fertile period finally getting its due. In his catalog essay, independent guest curator Philipp Kaiser lays out the now-popular version of contemporary art history in Los Angeles, identifying CalArts as its genesis and Helene Winer’s program at the Pomona Art Center in Claremont as its purveyor. Dismissing the Ferus Gallery origin story, he ignores the art world’s first international recognition of Southern California in the Finish Fetish and Light and Space artists in the late 1960s, whose respect for which rises and falls with prevailing trends in contemporary art.

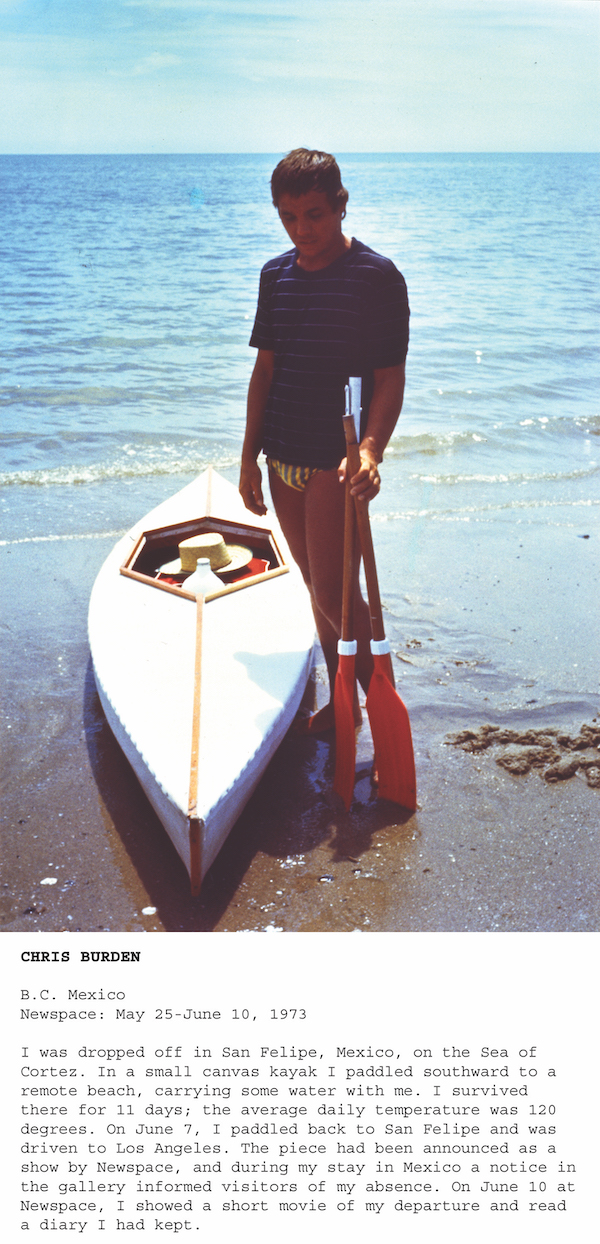

Chris Burden, BC Mexico, 1973

With the return of the art-critical spotlight to New York in the ’70s, artists in LA experienced the unscrutinized freedom to develop their distinctive version of conceptual art. Given Kaiser’s theme of disappearance, which encompasses appearance and the nearly synonymous dichotomy of absence and presence, the emphasis is on performance. Viewing the work of this period through the lens of disappearance is also a fashionable approach, initiated by Thomas Crow in his catalog essays for Pacific Standard Time shows in 2011 and echoed in Alexander Dumbadze’s 2013 book on Ader as well as Kaiser’s own Goldstein exhibition in 2012. (Burden, by far the best artist of the group, was yanked in for moral support and his well-established reputation.)

“Disappearing” supplies a thematic boundary for the number of works included, especially given the productivity and variety of Burden’s career, and a compelling hook. Ader tragically perished in his small sailboat—his body never found—during an art-inspired cross-Atlantic voyage in 1975; as a graduate student, Goldstein was buried alive in a CalArts performance in 1972; in White Light/White Heat, Burden was unseen for 22 days while he lay hidden on a high platform during his solo exhibition in 1975. Connotatively rich and multivalent, the individual works in this exhibition offer much more than simple disappearance. Yet, as Kaiser reports in his essay, the artists’ disappearances can vouch for Roland Barthes’ contemporaneous theory of the death of the author, and, apologizing for his men-only exhibition, coincide with the appearance of feminist art in Southern California.

Bas Jan Ader, Ocean Wave, June 1975

Conceptual art in LA was substantially different from the art-historically legitimate version in New York. As we know from Californian John Baldessari, humor was an essential ingredient. Ranging from slapstick to grisly, humor characterizes works such as Ader’s 16mm film Fall 1, Los Angeles (1970), in which the artist tumbles from the roof of his house, and Burden’s performance You’ll Never See My Face in Kansas City (1971), represented by the knitted ski mask the artist wore for the duration of his three day visit. Works of this period in LA are also distinguished by their use of modern technologies, especially recording devices associated with Hollywood, including film, video, photography, and sound, in contrast to New York conceptualism’s emphasis on written texts supplemented by still photography.

“Disappearing” made optimum use of the museum’s exquisitely minimalist Tadeo Ando-designed building, commanding the entire first floor with a generous installation that allowed the viewer to recalibrate between each of the 40 intensely thought-provoking works. One of the building’s distinctive features, a large oval gallery just inside the entrance to the exhibition space, provided an eloquent introduction: isolated and spotlit, the empty vitrine of Burden’s Disappearing (1971) contained only a small title card explaining, “I disappeared for three days without prior notice to anyone.” Outside the oval, the words of Ader’s Please Don’t Leave Me (1969) were painted in large black capitals on the wall. The preparator’s casual brushwork, carefully copied from a photograph of the original installation, only reinforced the self-consciousness of Ader’s urgent plea. His dramatized sincerity resurfaced in a wall-sized dual slide projection, Untitled (Sweden). On the left, Ader stands in a forest; on the right, he is prone among the forest’s felled trees. Also from 1971, the 16mm film Nightfall depicts the artist stoically smashing a string of illuminated lightbulbs with a large rock.

Chris Burden, Three Ghost Ships, Spoletto festival installation, 1991

Projected on 16mm loopers, several of Ader’s and Goldstein’s films played continuously in one of the most engaging galleries. Goldstein’s mesmerizing A Spotlight (1973) was shot in his dark, cavernous studio where the beam of a large spotlight chased the artist while he frenetically attempted to elude its glare. The soundtrack echoed the stomping shuffle of his unseen feet. Burden’s calculated, if equally tenacious performance, Death Valley Run, was represented by maps, photos and the racing bike, fitted with a miniature motor, ridden by the artist across an 84-mile stretch of Death Valley in 1976. His more elaborately mechanized and fully rigged sailboats, intended to sail unmanned across the Atlantic Ocean, Three Ghost Ships (1991) occupied a soaring double-height gallery at the Modern. Burden’s GPS-guided boats provided a high-tech counterpoint to Ader’s ill-fated voyage, the centerpiece of his final trilogy, In Search of the Miraculous. The first part, subtitled One Night in Los Angeles, includes 18 photographs recording his trek on foot across Los Angeles, captioned with lyrics from the 1957 song “Searchin.” The photos were included in Ader’s show in 1975, where his art students from UC Irvine sang 19th-century sea shanties at the opening reception. An audio recording and projected color slides of the choir, along with sheet music for the shanties, were included in “Disappearing.” Nearby, a film documenting Ader’s preparations for his ocean crossing played on a small monitor. The third installment of In Search of the Miraculous, intended to mirror the first part, was to be a one-night piece made in Amsterdam, which he never arrived to complete.

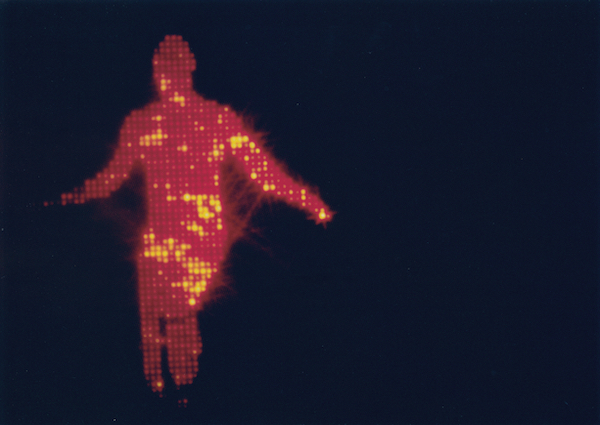

Jack Goldstein, The Jump, 1978

Disappearances caused by the destructive forces of war were implied by the Russian tanks represented by 50,000 nickels and matchsticks in Burden’s The Reason for the Neutron Bomb (1979) and by several of Goldstein’s massive black-and-white paintings depicting WWII night-bombings. Unlike the intimacy of the show’s early films and performance documentation, this bombast was tempered by the modest spectacle of Goldstein’s sparkling 1978 film, Jump. Near the end of the show, Jump called to mind Goldstein’s exquisite, single-subject color films from his Pictures period, which were thematically excluded from the exhibition. This was one of the rare group shows that left me wanting more.