The individual works in Devin Troy Strother’s 2010 solo debut were tiny spectacles, collages full of frolicking figures and bright shards of colored paper that extended beyond the confines of the frames. In his current exhibition “They Should’ve Never Given You Niggas Money,” he expands the spectacle by creating an immersive installation, bombarding viewers with his iconic imagery—childlike renderings of heads and bodies with huge afros and simple features—in multiple mediums: collage, paint, neon, wallpaper and carpet. The results are akin to viewing art in a fun house.

Although he indulges in toying with cultural stereotypes, specifically those related to African Americans in popular culture, like the banana or the Nike swoosh, and makes reference to rappers and comedians (the title of the exhibition being a line taken from a comedy sketch by Dave Chappelle), insisting there is humor in the work, his critique of these representations is half-hearted and more a celebration of what a young savvy talented black artist can get away with in 2015. His approach has roots in assemblage and the works of artists like David Hammons and William Pope.L, yet it has none of the suaveness and cunning of his elders. His pieces are direct, abrasive, in your face and impossible to ignore.

Devin Troy Strother, A stack of niggas on a plate, 2015, courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery/photo by Alan Shaffer.

Strother’s large scale neon and aluminum sculptures have been professionally fabricated; he overlays these sleek black surfaces with bulging blue eyes, wide red smiles and textured afros. The individual heads are combined into a series of totemic sculptures titled a wave or a tower or a stack of niggas on a plate (all works 2015) and presented in the half of the room wallpapered with holographic film. The other half of the gallery is painted Pepto Bismol pink and features a series of mixed media panels entitled sequentially from 1 to 10 niggas on a nana. In these works, paper doll-like nude figures ride on yellow bananas that float on a pink ground similar to the gallery’s wall color. Strother turns the room into a psychedelic environment, indulging in the overflow of visual stimuli.

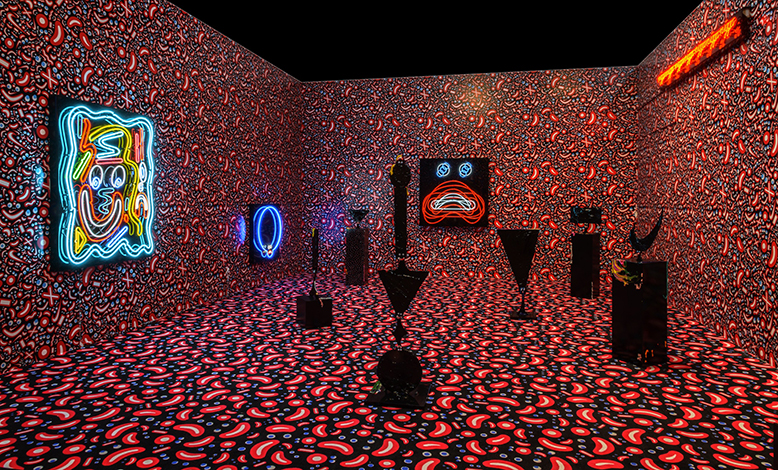

The front gallery is calm in contrast to the wallpaper and carpet-covered West gallery installation, What if Yayoi Kusama had Jungle Fever? The frenetic pattern of the all-over imagery references the visual intensity of Yayoi Kusama’s installations; however, the allusion to “Jungle Fever” is Strother having bad-boy fun. His offhand nods to other artists in addition to Kusama—a text-based painting plays on Ruscha—is Strother’s way of situating his work in relation to what he sees as important art historical precedents. But this is not necessary. Strother is unapologetic and sarcastic on race and gender. While he might take cues from popular culture and those who came before, he is making uniquely original works that have grown from funky hand-made works on paper into over-the-top installations that fuse fabricated and hand-crafted elements. These solidly identify Strother as the witty, creative mastermind of an inventive world. While at this moment his works are not overtly critical, they are nonetheless memorable and engaging.