Picking up Highway 62 on the outer edges of Palm Springs takes you up to the high desert in which you drive through endless urban scar tissue a block deep on either side of the road, until you get to Andrea Zittel’s 50-acre spread. Leaving the highway you ascend on a precarious unpaved road to her studio, which is everything the landscape isn’t. The studio is a spacious, clean, immaculately rectilinear sequence of three rooms. The second of these is devoted to the fashioning and firing of clay, while the third is full of looms for weaving fabric. The first, equally tidy room is smaller and contains Zittel’s work table as well as her drawings on the walls, the most striking of which are crisp, clean black planes intersecting at right angles. The whole set-up feels quite corporate, an impression reinforced by the names that Zittel has given to her workplaces—from a Brooklyn studio in the 1990s she called “A-Z Administrative Services” to today’s “A-Z Management and Maintenance Unit.”

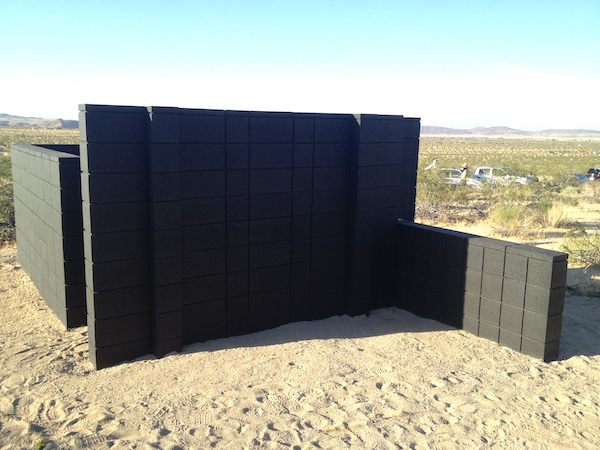

Andrea Zittel, Planar Pavilions at A-Z West, 2019

An efficient management hierarchy proved to be in place when (because Zittel wasn’t available) an articulate, knowledgeable assistant gave us a tour of the site. By the end of this tour, my impression of Zittel and her work had become more complicated. It was the last stop on the tour that did it. We had arrived at a viewpoint looking out over the landscape, with Highway 62 a thin strip far below us. Between us and it, we could now see something I hadn’t noticed on the drive up. Scattered over the hillside are black walls that intersect one another like the black planes in the drawings seen earlier. In three dimensions that somehow sink into the landscape, Zittel’s abstractions take on a new meaning, and a powerful ambiguity of the kind that only art can have.

This installation is titled “Planar Pavilions at A-Z West,” and Zittel herself seems to relish its ambiguity when she writes that the “structures” could be “still in a state of construction” or might have a “function similar to ruins.” The latter, especially, gives them a kind of substance by grounding them in the history of the landscape they inhabit. They allude, for example, to a “hare”-brained scheme the government had after World War II when it offered to build “Jackrabbit Housing” in the desert for returning veterans. It was a kind of homestead that, without providing water, electricity or paved roads, proved even less viable than the homesteading on the Plains of the Great Depression. Roofless, floorless vestiges of such housing are still to be found secreted, like Zittel’s configurations of walls, in the neighboring desert. Moreover, since they were built, Zittel’s roofless walls allude not only to the past, but, as only art sometimes can, to the future. In their dead blackness, they presaged the few charred walls here and there that are all that remains of the tragically misnamed town of Paradise, California.