Activities are often pierced by interludes that have little to do with them. One’s reading, for instance, may be interrupted by thoughts, noise, a graphic on the opposite page, a text message. This sort of discontinuity is central to Paris-based Denis Darzacq and Belgium-based Anna Lüneman’s collaboration, “Doublemix” in which Lüneman’s earthenware pieces occupy cutouts inside Darzacq’s digital photographs.

In On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag expatiated upon the power of photography, describing a “negative epiphany” she experienced in a bookstore upon encountering disturbing concentration camp photos. A photograph can change a person’s life via poignant evocation or revelation of important facts. However, most photos are relatively picayune. Darzacq’s are unexceptional, depicting mundane scenes such as a running dog or a suburban tract house. What make his photos exciting are their interruptions by incongruous embedded 3D components.

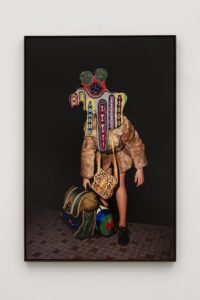

Lüneman’s painterly ceramic pieces play on elements of each image even as they clash with—and often dominate—the overall picture. Sometimes the clay elements seem to belong, as in Doublemix No. 52 (2016), in which two sculptural forms evoking a hollow geode and a mineral vein extend the photograph’s depicted stone formation into three dimensions. More often, they overtly disharmonize, as in Doublemix No. 45 (2015), where five gaudy amorphous pinch pots halo a grinning man in the driver’s seat of an old-fashioned car. This improbable juxtaposition is humorous, almost kitschy in its evocation of thrift-store finds and kindergarten crafts; it might be ironic were it not so earnest and mysterious.

Denis Darzacq & Anna Lüneman, Doublemix No. 51, 2016, ©Denis Darzacq, courtesy of De Soto Gallery.

Considered in the context of modern life’s complex webs of incongruities, the seemingly arbitrary photo-ceramic collisions become meaningful. In Transient Images: Personal Media in Public Frameworks (2011), Eric Freedman elaborates Sontag’s aforementioned narrative: “… just moments before she had been engaged in another act—perhaps meandering, browsing, or reading. Within this chronology, the act of viewing can be understood as an interruption…” Sontag’s is a dramatic example, and this phenomenon is nothing new, though perhaps it is more frequent now; abetted by the technologically sophisticated trappings of our image-centric society, an individual might experience similar, albeit less meaningful, interruptions on a daily, even hourly basis.

Darzacq and Lüneman’s artworks could be thought of as simplified analogues of such divergences. Their randomness and duality appears rooted in Dada and Surrealism; their combination of media falls into a long tradition classified by shows like MOMA’s 1970 “Photography into Sculpture.” It could be argued that their compositions are ingenuous compared to the more complex oeuvres of photographer-sculptors like Robert Heinecken, Ellen Brooks, Jerry McMillan, Carl Cheng, et al. Yet perhaps the strength of Darzacq and Lüneman’s work is in the stark simplicity of their dichotomies: whimsical abstraction and commonplace representation, earthen and computerized, the ancientness of clay and the newness of digital photography and printing. We are so distracted by quotidian exigencies, computer diversions and commercial barrages that we hardly consider the extent to which we oscillate between different senses of time, place, modes of thinking and reality. Darzacq and Lüneman’s hauntingly simple dialectics give occasion for pause.