On a sweltering September afternoon, I visited artist Astra Huimeng Wang as she was in the final stages prepping for her first solo show of paintings at Make Room LA. Her studio is nestled above a discount clothing store in LA’s Fashion District, where crowded shop windows are filled with children’s pajamas that double as Disney costumes. I paused before an outdoor rack of candy-colored tulle princess dresses being tossed about by the hot wind. It was as if these festive garments were little spirits preparing me to enter Wang’s work. Arriving at the studio and looking at her paintings felt like confronting Renaissance polymath Giulio Camillo’s Theatre of Memory: the relics of tender moments filling the audience seats for a single spectator who stands alone on the stage.

Wang is an LA-based multidisciplinary artist who grew up in Hohhot, in China’s Inner Mongolia region. She has held residencies at Otis College of Art and Design, earned a MacDowell Fellowship and most recently participated in the group show “Machines of Desire” at Simon Lee Gallery in London. In Wang’s latest body of work the viewer is invited to reflect upon familiar moments from Western ceremony. As we spoke about decorum and decay, Wang gleefully showed me her collection of tossed-away ephemera: cutesy wedding cake toppers, tiny 1950s toys including a functional, doll-sized oven and refrigerator, and lavish wedding albums. As she turned to the faded picture that inspired her painting for the group show “Machines of Desire,” she commented on the fastidious planning and care that goes into a wedding day “so it can be preserved in the decadent album, only to be discarded and end up in my hands for a dollar at a flea market… all these precious moments.” Wang told me how growing up before social media in a culturally homogenized Inner Mongolia, her only access point to the West was literature and films: “If you grew up in Western culture these relics are what’s left of important moments, but to me they were condensed representations of Western civilization and utterly disconnected from reality. All were part of the fiction I consumed.”

Exposing fiction as fiction has long been Wang’s aim and what first led her to experiment with flocking techniques. She told me, “In one of my earlier projects, a three-day performance, four people were having a dinner party in a 10×10-foot box-like movie set with red velvet curtains on three sides. I was referencing Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie where the rise of a red velvet curtain behind the dinner guests reveals that they are actually on stage. The idea that red velvet suggests a departure from reality became so symbolic to me that I began experimenting with red flock to create these velvet-like surfaces when I started to make sculptures.” I was vaguely familiar with flocking as the artificial snow sprayed onto Christmas-lot pine trees giving those in warmer climates the illusion of a white Christmas, and as the synthetic lining used inside children’s jewelry boxes that lends a gauche, regal-adjacent opulence. I asked Wang more about its origins and about working with the material. She explained that the process of attaching ground fibers to fabric with resin originated in China 3000 years ago and only later was used to paint onto hard surfaces: “Flock-painting needs to be done like a marathon because once dry, it’s almost impossible to make any adjustments. I’d sometimes work 15 hours without any breaks to get something right. The process requires skill, precision and just enough room for coincidences. It feels akin to what happens in any performance.”

A Continuum of Positively Captivating Behavioral Expectations, 2022. Flock, acrylic, acrylic medium on birchwood panel, 60 x 60 inches. Both courtesy of the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles.

Right after this, the studio’s A/C unit broke and we watched it, like a stubborn rain cloud, slowly dripping fluid down onto the materials below. “Happy accidents,” Wang mused, “that’s just the effect I am hoping for with the final bit of red I am adding to the wedding scene.”

Wang had been finishing a painting where a couple lovingly clasp hands over a knife just before slicing their wedding cake. In Western culture, the cutting of the cake as husband and wife is another wedding “micro-event” and as important as the tossing of the bouquet. In Hollywood Romcoms, the cake has become another predictable source of hijinks, its fragile nature always inviting a disaster. We’ve come to expect the cake will be destroyed in transit, a child will scoop his hand in for a greedy bite, or a Labrador will run off with the topper. In the painting it might appear that this scene is going off without a hitch—meaning the couple have made it to the moment unscathed—but the framing renders the couple headless and we cannot see their expressions or the guests’; the flocked outlines show the cake, the moment—the couple are already melting into time.

As I considered this tidal destruction I was reminded of Auden’s poem “As I Walked Out One Evening”—specifically the line “the glacier knocks in the cupboard” and his promise that pesky time will always cough when we would kiss. But Wang speaks with sincere wonder and affection about the ways these interruptions function as “the moment of crisis,” the dramatic instance where nature and time disturb the little one-act play we are forever constructing for others. She mentioned a similar occurrence in an early performance piece, “A Beginner’s Guide to the Art of Throwing the Perfect Chocolate Fountain Party,” where during the shooting a fly snuck in the studio and buzzed around the fountain. “Of course, there would be a fly at this dinner. The actors sat for three days at a set table with decadent food and warm chocolate—it’s delicious! It became one of my favorite elements in that show,” she proclaimed.

Wang in her downtown Los Angeles studio. Courtesy of the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles.

There is something revolutionary in Wang’s process of inviting ruin into Western ceremony, informed perhaps by a lifetime of engaging with the Western canon for the sake of learning English, and subsequently seeing herself rendered on the page through an Orientalist gaze. She showed me a brimming binder where she collects literary passages to work with and through in her art. Her latest show’s title, “In My Experience the Spider is the Smallest Creature Whose Gaze Can Be Felt,” is lifted from a passage in Iris Murdoch’s 1954 novel Under the Net where the speaker Jake experiences the uncanny sensation of being watched and finally notices a set of masks “whose slanting eyes were turned mournfully in my direction,” commenting on their “Oriental mood.”

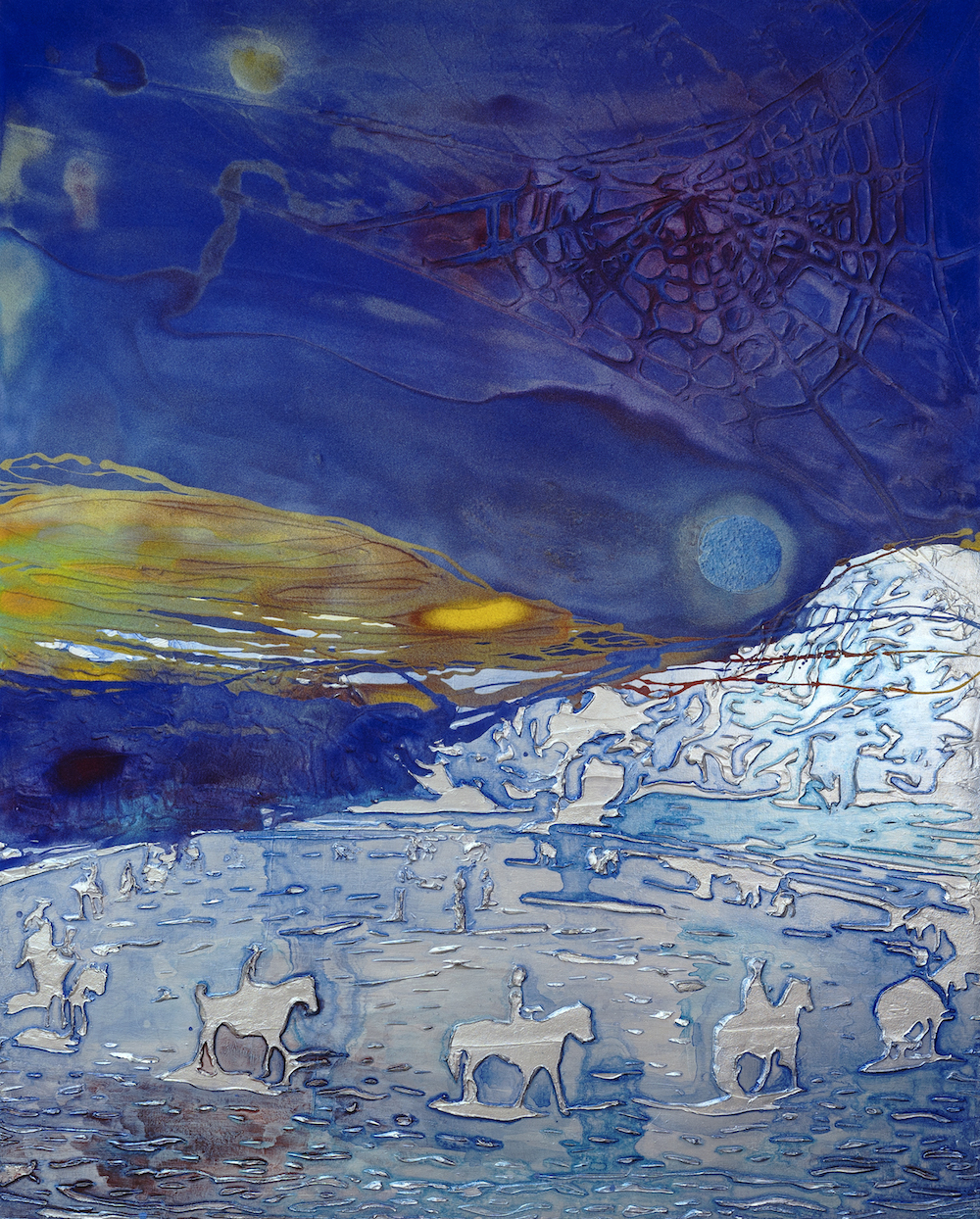

The sense of being watched is most keenly felt in the painting Beneath a Dreamy Chinese Moon, Where Love is Like a Haunting Tune (2022). Here horses are being paraded in a circle; the sense of pageantry and showmanship is cleverly undermined by the ice-blue flocking that creates a chilling effect and casts a ghostly mood. All we see are the horses and riders’ amorphous silhouettes as they melt into the valley landscape. While the show goes on, the aubergine sky looms and draws the eye to a second, truer splendor—nature’s. The patch of yellow and tiny green clouds lend their own lighting effects toward a different focal point. Rather than stage footlights, our eye is drawn to an aurora borealis that calls our gaze out beyond the constructed reality. Where a stage curtain might hang, we instead see a sprawling spider web. The flocking here blurs the delineation between web and spider body, of spectator and spectacle.

If the Modernists’ inheritance this past century has been to see nothing but “a heap of broken images,” Wang flips through the discard-pile of cultural memory, repurposing these fractured pictures to create a new narrative in painting: one that draws our eyes to the red velvet, the spectacle, all the while winking from stage left and asking the viewer—Who is watching whom?