Everything about the way we talk about art in public is vestigial, left over from the birth of print. Once upon a time this conversation was done entirely with ink: ink was expensive, photographs of art were more expensive and photos in color were even more expensive than that. So what they did was send someone out to turn the pictures into words, and then printed the words. As a raw verbal description was unsatisfying, they also injected opinions—and the standard Show Review was born.

This is not to say that discussing art is useless. In an era where any gallery can give web visitors a decent (or at least better-than-words) impression of what a show looks like with an hour and an iPhone, things have changed enough in the last hundred years that it’s worth asking whether we need to keep talking about art the way we do.

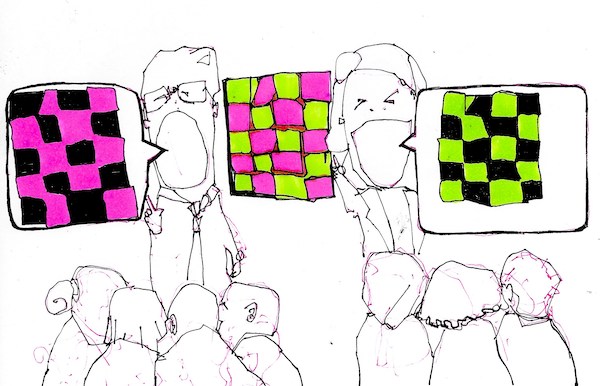

Twice in the last week I’ve read reviews of the same works of art that not only disagreed on good/bad but on things that, back when I was a fact-checker, we might call facts. One review says that whatever else you think, it’s technically assured; the other says the creator—once an acknowledged master—has clearly lost all control of the medium and materials. This one says the social commentary on income inequality feels very real and present; the other one (crossing a long-ago obliterated line between review and personal attack) says they doubt the wealthy creator even cares about ordinary people. As any judge will tell you: motive is a thing. You can prove the reasons for doing things—or at least give your evidence.

It’s easy to justify the continued existence of a galaxy of lone, speculating voices if we assume the reasons people want art reviewed are terrible: they enjoy seeing slightly more articulate versions of their own point-of-view under a masthead, they enjoy watching people yell at each other on Twitter, they’re fine with one person’s art being no more than an excuse for someone else’s exercise in style.

While it may be no simple thing to explain why we want to read other people’s ideas about works of art, if that reason is anything remotely noble—to help us articulate our own thoughts about this and other things later, to spur us to think more deeply on it or the world, to use the work to gain insight into the variety of ways anything is seen by people with different assumptions, to walk away knowing more than we did walking in—there is no point in the “competing monologue” model of criticism.

If one critic says they can’t imagine what the message is meant to be and another floats four plausible theories of what the message might be, make them talk to each other, and then publish that.

This turns the fundamental characteristic of opinion in the internet age—the ability to always find conflicting opinions on any subject, no matter how banal—and turns it from a bug that creates either self-satisfied echo chambers or self-cancelling hate-noise into a feature. Dialogue forces both sides to make deeper and better-supported arguments, and it forces them to consider ideas neither would have to think about if left to their own devices. When those who disagree can pick at your examples, ideas have to be explored in detail—and when they’re at the same table or on the same microphone you have to put up or shut up. Dialogue between people who fundamentally disagree produces a criticism that is more than the sum of its parts.

Whatever we get out of the Times saying one thing and the Big Glossy art magazine saying the opposite, we’d get a much bigger and higher-quality dose of it if they had to contend with one another as if whatever they were saying mattered. What if they don’t like each other and can’t get over it? What if nobody wants to pay for that? Well fuck them: they want what they say to be taken more seriously than the average thumbs-up or thumbs-down emoji and they want to get paid for the privilege but they won’t fight for it? Every artist has to endure this shooting gallery, there’s no reason (well: no good, noble, self-improving reason) that their gatekeepers should be exempt.