If you’ve been to a museum lately you’ve noticed all the not-art. The artist’s notebook, the artist’s ticket to Switzerland, the fragment of the stage still containing the burn-mark from the performance, the suit the artist wore during the performance, the chart the gallery made to keep the pigeons’ names straight before they were fed in alphabetical order into the wood chipper. I’m not talking about things that are art but look like everyday materials, I’m talking about the everyday materials that nobody involved even claims are art that are shown in the name of deepening the learning experience or just to have something to look at when the show’s celebrating something that’s so ephemeral or conceptual there’d be nothing much else to see otherwise.

In principle, there’s nothing wrong with more stuff. In practice, however, there is a very real philosophical and PR problem since museums are also still showing the aforementioned “things that are art but look like everyday materials.” While the critical studies major may be carefully reading wall labels to see what is and isn’t supposed to be art, the average viewer is likely to move through the halls at a clip, only slowing down for things that catch their attention—and increasingly what catches a contemporary museumgoer’s attention is not art, but this spectacle of curation.

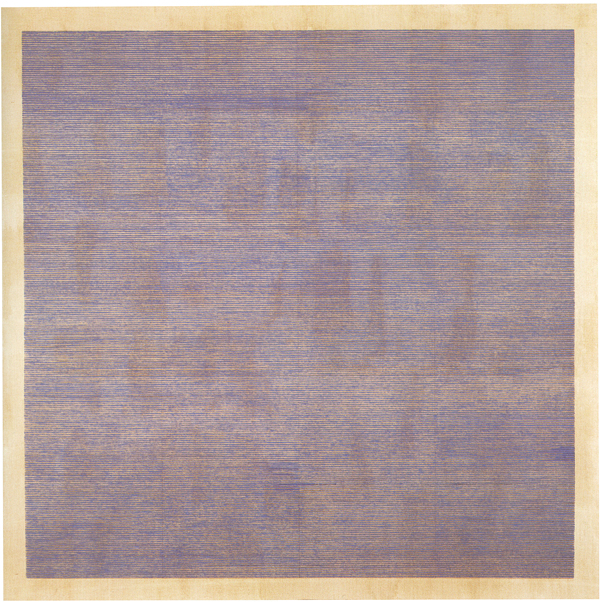

Is this an Agnes Martin or an actual graph? Is this an automated slide show because the only documentation of this piece was on 35mm slides or because the piece is a slide show? Seeing something that, at 40 feet, looks like it might be fun, walking up to it, finding out it isn’t, then reading a wall text explaining it isn’t even art and then doing it all over again in another room and finding out it’s still boring but is—this psychophysical loop is now half of the museumgoing experience.

Is it interesting? Why was it supposed to be interesting? Who decided it was? Next object. Within this context, the everyday-object-as-art is no longer a shocking or mysterious wolf lurking among the sheep of more recognizably arty art, it’s just a conspirator in a spectacle of curation that forms an increasingly large part in the lives of both museums and museum-friendly contemporary art. You walk away sure of one thing: someone has the power to curate. Who that was or why or what they were curating can easily escape the viewer who just ducked into the local Center, Space, or Project but you are entirely sure someone was curating: things definitely got pointed at and put on pegs. Rooms definitely got curtains put in front of them and got painted all black and walls definitely got videos projected on them (Were they short films that hadn’t gotten to the good part yet? Video loops? A documentary on the artist whose show it was? Who knows? Who wants to?). The most powerful statement this experience makes is: someone had the power to do this.

Having just got back from the much-maligned Miami Basel it’s hard not to draw a direct contrast—the 83,000 Floridians flooding the aisles of the Miami Convention Center may not know that you don’t drink champagne near the Keith Haring and you don’t wear a burgundy dress with wicker sandals but they do know what they’re looking at: this is a showroom, like where you buy cars and ambitious chandeliers. The spectacle of curation—its ability to bemuse and baffle and make you feel small (“You don’t now what this is and you never will unless you read our wall”)—is entirely absent. The only power dynamics on display are so familiar to any American—buyer, seller, luxury object—that you can ignore them.

How many times have you thought: I’ll give it a shot—went in, found a place on yourself to stick the little sticker, deciphered a colored map, and walked from Gallery A to Hall G feeling nothing more than the constant weight of having to decide which pedagogical rat maze of wall paragraphs and cordoned furniture the 20 bucks you just spent is going to force you to figure out? The science museum wants to explain things, too—but it’s plasma and dinosaurs. Not, like, why someone with a hyphenated name cut a newspaper in half. Never have we been shown so little and asked to work so hard to see it.