Regular readers might remember a column from a few months ago where I got loud about how publicists are just one more way the art world has found to reward privilege by granting it more privilege so then started a search for the most obscure artist in LA so I could write about them instead.

I got a lot of emails. I asked entrants for not only declarations of neglect but evidence of it, so this got real sad real fast—in the Ming period, Ch’ên Chi-ju listed in his Shu Hua Chin T’ang the adversities that an artwork might be made to endure:

To fall into the hands of a peasant. To be pawned. To be given to haughty people. To be cut up for making coats and stockings. To be left to an unworthy son. To be stolen by thieves. To be exchanged against wine and food. Calamities of water and fire. To be buried in a tomb.

I have now seen them all, in living jpeg—but I did eventually find the most neglected artist: it’s Patricia Chow. So this column is about her.

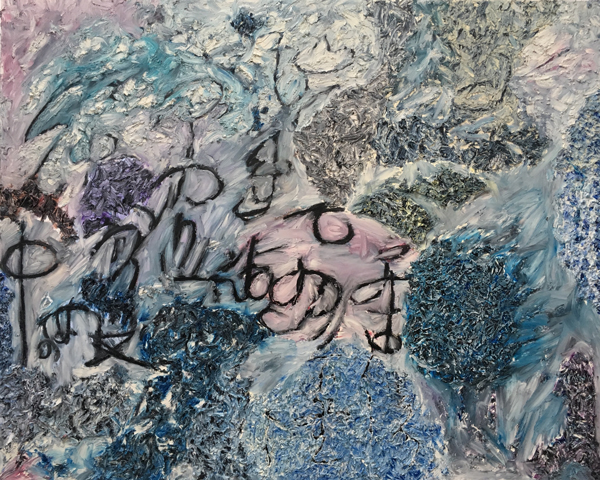

Patricia Chow, Bad Luck Brings Good Luck (2018), courtesy of the artist

She’s a perfect example—like so many utterly American Angelenos, Patricia Chow’s art makes a point of pointing at the symbols and signifiers of an ethnic identity she has an ambiguous relationship to. Her life isn’t Chinese but her background is, her images aren’t Chinese but the images in her images are: the great wall, a famous landscape painting reworked, the symbol for “luck.” Chow mentions what happened the first time people from actual China saw the work:

Chinese calligraphy is part of this venerated tradition going back centuries where you basically copy old masters for years (you know, respecting your elders and all that) and then if you’re really good you’re allowed to make some minor stylistic innovation and that’s considered a new style. One of the things you can’t mess with is it’s always done in black ink. Even avant-garde calligraphy still holds to this medium. So it’s a little shocking to see bright colors and paint being used when I’m obviously writing characters. I believe her quote was “How can she do that!?!!”.

In its most elegant form, this suspicion of newness in traditional Chinese painting is based in a longstanding belief in the marriage of art to wisdom.

The Strange Scholar of the Melon Field, a respected Chinese critic of the Ch’eng period, had this advice for painters: One should start by seeking to establish what the mountains, stones, water and trees ought to be and not venture to throw out scattered thoughts in accordance with the impulses of the heart, but carefully follow the rules of the ancients without losing the smallest detail. After some time one will understand why one must be in accordance with nature, and after some more time one will realize why things are as they are.

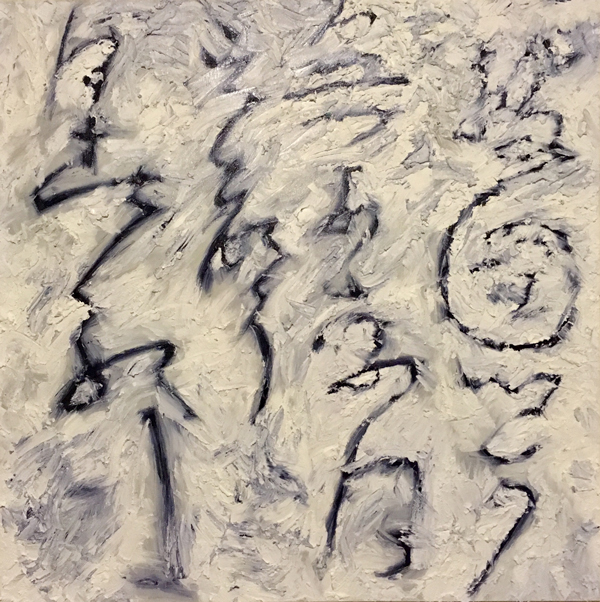

Patricia Chow, Outremer (2017), courtesy of the artist

Chow’s art is all “scattered thoughts in accordance with the impulse of the heart” because, like anyone smart working now, the reasons why things are as they are aren’t good reasons and the reason we are painting them aren’t traceable to any wisdom we assume they possess. She endlessly paints “fu”— the character for luck, fortune, prosperity—in different styles, as if asking it, as if asking the Chinese language, as if asking language itself not how did we get here but why did we get here? And looking for a language to use that will get language to answer.

The connection of art to wisdom has taken a beating lately, there are only a few artists whose wisdom even artists tend to agree on—Goya, Kara Walker, Giacometti maybe—because the big mood is however much we like art, all its wisdom got us was… this. Beyond war and racism being bad, can art even tell us a thing about a world?

Patricia Chow, Poem to a Painting (2017), courtesy of the artist

When the Ming critic Ch’en K’an said The great genius of the Yuan period, Huang Kung-wang taught that the thing which is to be most avoided in painting is sweetness. It is made up of luxuriant elegance and mellow ripeness. He was maybe being weird and vague—but was he really any more weird and vague than a modern critic using their favorite artist’s deft sense of theatrical timing to declare they’re an incisive voice negotiating the liminal hybridities of the modern era? What are we doing pretending beauty gets us truth?

Chow’s work approaches a central problem of the artist in the 21st century: why say things? Facts don’t matter, why should these sidelong evocations of them we call image? Why did anyone ever think this would work?

If there’s a more 2018 gesture than beating your head on a wall I don’t know what it is.

0 Comments