Your cart is currently empty!

DECODER

I know a curator who used to work for Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen—her job was to look through all the old press clippings and organize them. “That must’ve been interesting,” I said, “did you notice anything?”

“Well,” she said “in the ’60s, Carolee Schneemann was everywhere.”

Right now she’s in the Getty, specifically: on a stage, in the long and flowing clothes of a woman of a certain age whom one suspects both owns and operates a garden. The coral around her neck and the red velvet flowers on her sleeves are counterpoint to the red-patterned rug upon which she and her blonde and nose-ringed interviewer sit in blonde-wood chairs, both pairs of hands folded on black-pantsed laps, looking down diagonally—not at us, the audience, but at a flat screen at the foot of the stage.

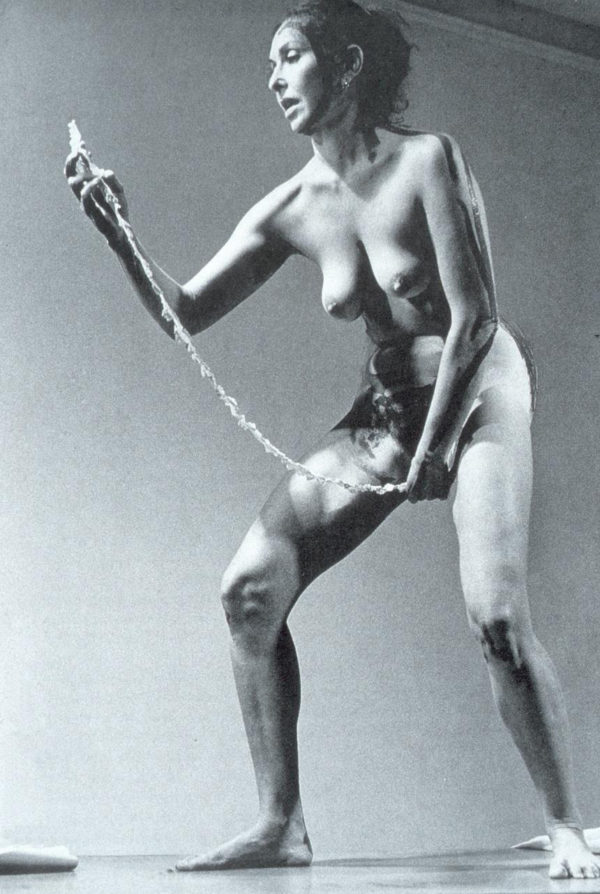

Its back is to us but it’s clear what they see on its screen is exactly what we see behind them—a massive Schneemann, younger and 20-feet tall, nude, knees bent like a batter in a ballgame, one arm bent like Hamlet with that skull, one hand in her crotch, face concentrating on the leading edge of what she pulls from it—a printed-paper streamer longer and thinner than a CVS receipt—from which she reads.

This projected giant—captured from a low angle (she’d been on a table) in ’70s Kodak gray—is in the middle of Interior Scroll: “an essential moment in performance art history,” “a landmark performance,” “a groundbreaking piece of feminist art,” an “historic performance.”

“Put that thing away!” the artist says, and the interviewer obediently clicks to a different slide.

Dipping into the slow, low stretched vowels of graceful midcentury feminine dinner-party dismissal (“Really, Clarence …”) it becomes immediately clear that Carolee Schneemann doesn’t think much of Interior Scroll—or, to be more precise—thinks we think too much of this lurid image, neglecting 50 years of other work: paintings, constructions, actions and happenings, writing and artists’ books.

There is a certain kind of viewer who’d ask, Well, what do you expect? It was 1975 and you pulled something out of your vagina. It’s 2018 and we should be able to agree: This viewer is boring. There is something very sad about a society whose reaction to the labial threshold being traversed voluntarily by a heretofore unexpected entity is to note it and go back to throwing money at stacks of carefully lined-up bricks. Yet this is largely what happened—it wasn’t until the ’90s that her work was widely recognized and even then, the image presented to the public by the art establishment was mostly just: this piece. This exact photo of this piece. She tells us people all over the world have re-performed it, including a man who made an anal scroll. “It’s my fur-lined teacup,” she says.

Speaking of butt performance: Ron Athey is in the audience. Noted for causing NEA mayhem in the ’80s for “spraying HIV-infected blood on the audience” (he didn’t and it wasn’t) he too knows the tedium of being trailed around by a sensationalized “Free Bird” while volumes worth of other work go undiscussed.

Eva Hesse didn’t have this problem, nor did Judy Chicago. What Athey, Schneemann, Meret Oppenheim (of the fur teacup), and Cosey Fanni Tutti (who never quit her day job until she joined a band) have in common is: Sex. Too much of it and the wrong kind. There’s no rule against it, but there’s a quota, and it is low—handed out like a dog treat when the art audience is deemed sophisticated enough to deserve it. It didn’t have to be that way: Schneemann was everywhere—she also knew everyone: Warhol, Allan Kaprow, Red Grooms, Steve Reich, Jim Dine, Philip Glass, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Rauschenberg—Stan Brakhage helped her find the one lab where you could reliably take an erotic film to get processed (to avoid the FBI, a psychiatrist had to file paperwork certifying that the 100-feet of film contained a study of the cross).

The porn processors were scandalized by all the oral—“Does the lady like that?” one asked, red-faced. She did. This was 1975. How many people were not getting eaten out on account of all this squeamishness? And what eminence allowed to grow gray will sit on that stage in 2061 saying “Well, it was the 20teens—nobody knew anything back then?”