Your cart is currently empty!

DECODER

In the line to vote, a woman from Guatemala is very proud to be voting Hillary and a guy from Silver Lake is very proud to be voting for marijuana, but they’re both like “Why is there a two-party system?” “Well,” I say, “the thing is that the parties have created strangely-shaped districts so that …” aaaaand now they’re asleep. Because they are only interested in the image—in the raw colors and shapes, the glandular reaction to faces, the heavy unshakability of a pictured thing in a mind’s eye.

The image is powerful but inarticulate. Strong on vowels (where the emotions are) light on consonants (where the details dwell and bedevil). I spent my afternoon in a line at the polls listening to citizens describing images they’d decided to vote for or against: the loud man, the angry man, the orange jerk with gleaming cufflinks, the experienced woman, the dour woman, the wrinkling mom who disapproves.

People like to look and people like to talk—but what they want to talk about and want to look at are different things. If Internet searches are anything to go by, people like to look at porn stars more than anything else—but it’s hard to tell if they voted no on Prop 60 because they were listening to them or just didn’t want to look at condoms. Artists get lots of traction on Instagram (which is nothing but pictures) but not so much on Twitter (which is words). Wanting a thing is not the same as wanting to know about it.

Art writing is always uphill: What kind of killjoy cares how the rabbit came out of the hat or the woman got sawed in half? Or, much worse: why?

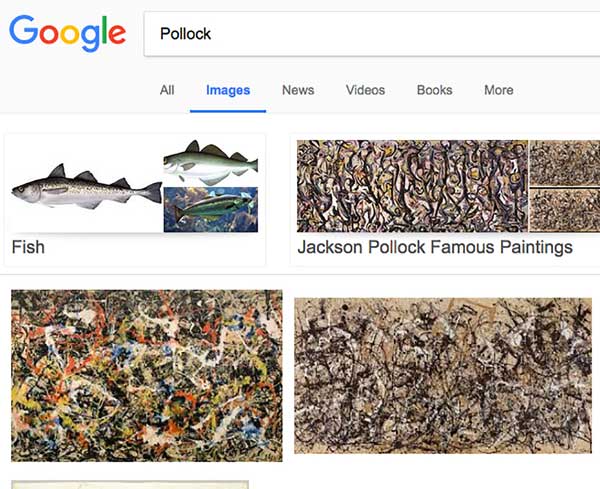

For years art magazines got away with opinion-mongering by using a monopoly on publicity to hold the images hostage to the discourse—if you wanted to see the art, you had to read their commentary on it. While it’s now common to see pictures with less context than anyone ever dreamed possible (Google “Pollock” and you get the art, but also movie posters and fish, all the same size) the frame through which we see it hasn’t so much evaporated as calcified. Put simply: Here at the beginning of 21st-century contextless art, we are still stuck with the interpretations invented when interpretation was fashionable.

This wouldn’t really matter except that the (19th-century-at-heart) institutions that keep art vaguely in the orbit of things a trust-fundless adult human can earn a living making feed on interpretations. The Brooklyn Museum, for instance, wouldn’t go near showing Marilyn Minter this year if her sexually explicit paintings hadn’t been reinterpreted as okay-actually-feminist in the years since she was first attacked for making them. Commercial imagery only needs to convince someone they want to look at it, but fine art requires convincing people they should—and so there’s no real end in sight for interpretation. There will always be a board member, a concerned citizens committee, a university chair, a long-term investor that demands an explanation. Without a way to at least plausibly claim to believe the painted lips on the fat painted cock is enlightening, the artist is out of a job.

New interpretations are a bit like new money or new power or new violence—repulsive but made necessary by the need to counterbalance the fact that old money and old power and old violence exist. Our art keeps moving and changing but our ways of talking about it are 20 years old and aging fast. Large things are still “bold,” didactic things are still “important,” video and installation are still “challenging” and people still act—despite all evidence—as if symbolism matters. The current system of preservation, propagation and prioritization of pictures and objects of galleryable demeanor rests on art writing—an activity that’s undergone a radical demotion from vaguely hip to hopelessly obscure. What pale glamour deconstruction can cast can now attach to anything from to the proper use of liquid eyeliner—like a parasite that’s outgrown its host, it not only no longer needs art or literature to feed on but has left them a drained husk. We campaign against irrelevance on dead slogans and promises nobody believes.