I recently overheard somebody make the observation that David Bowie’s death has “staying power.” It sounded like an idiotic remark at first but in this case it seems accurate. Sure, Bowie was one of the greats, an unfading star who provided an exhilarating soundtrack to countless lives, and a true gentleman who aged with preternatural grace, but it’s been more than three months since he kicked off and people still won’t shut up about it. It’s hard to think of a musical death that has engendered such a sustained outpouring of grief: Kurt Cobain, Lou Reed, Michael Jackson… none of these seem to come close.

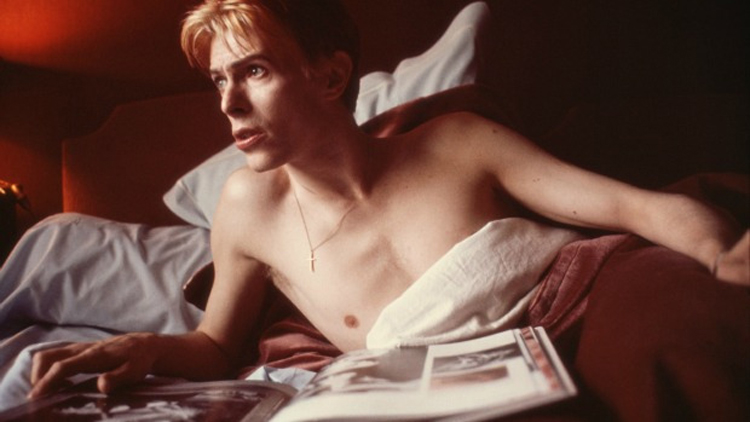

Nobody seemed as imperishable as Bowie. His alien quality and amaranthine beauty made him seem safe from the unavoidable humiliations of the flesh that afflict the aging. Such an ethereal being exposed as a mere mortal sent out a direct message: Nobody is going to buck the trend of mortality. Dylan, Jagger, Willie Nelson, Mark E. Smith… they’re all going to go, and it will be sad. The unsurpassable ’60s/’70s rock and roll era that is hard-wired into the collective psyche will pass from memory into myth as those who created it and those who bore witness to it pass on; and one day, about 30 years from now, there will be no remaining living links (just as there are no longer any living links with ’20s and ’30s blues).

And they’re going. Stars are dropping like flies. Bowie’s passing declared open season for death, heralding an unprecedented tidal wave of pop-culture passings: Keith Emerson, Paul Kantner (in fact, two members of Jefferson Airplane on the same day), Glenn Frey, Dan Hicks, Steve Young, Otis Clay, Vanity, Red Simpson, and just last week, Tony Conrad, and another of the seemingly imperishables, Merle Haggard—not to mention many more friends and acquaintances than usual. It’s hard to keep up. You just accept it: Who died today? Oh, so-and-so, that’s too bad… next.

Bowie’s death ushered in a new sense of vulnerability. Death seems more real and more inevitable than ever. From afar it could be glimpsed romantically, but at this late stage it’s far too close and cold for comfort. As the ’60s and ’70s generation reach their 60s and 70s, naturally, they are checking out in greater numbers. When one was in one’s 20s, 60 seemed ancient and, crunching the numbers based on lifestyle choices, one figured that one would be lucky to live that long. “We live for just these 20 years, do we have to die for the 50 more?” Bowie once belted out those words with great conviction. But when one has reached one’s 40s and 50s one finds oneself adopting a rather less blithe view of one’s impermanence and nowadays, when somebody dies in their 60s, it is usually lamented as being “too soon.” There’s not much point romanticizing death when one is middle-aged. Youthful melancholy was so much more pleasant.

Once there’s no more of you to go around, people can’t get enough of you—you can do no wrong after you’re gone—and while not wishing to appear unduly callous, in Bowie’s case, there’s no room for anymore grief, it’s better to save it for somebody who isn’t getting their fair share, and there are already enough possessive and self-serving eulogies along the familiar lines of “Those of us who knew him personally can attest to what a sweet and gracious man he was; I once held his baby in my arms; the last time I saw him he hugged me,” etc. …as if hugging you was his most notable achievement. Please tell us more about your relationship with the deceased.

But, of course, one does tend to remember these encounters. Everyone has their story. And why not? Here’s mine: In common parlance, Bowie and I were once Eskimo brothers, in that we visited the same igloo. It was inhabited by a buxom and hirsute woman of Spanish descent. She divulged that Bowie had more stamina in the sack than any man she’d ever been with, which made perfect sense, and made me feel lackluster by comparison—which was fine, as I was lacking lust for her; but the thought that I was indifferent to the charms of somebody that Bowie, who had his pick of the litter, made tracks for whenever he was in town, was puzzling but somewhat gratifying to my young mind. Then again, “it was a god-awful small affair.”