Throughout his long and distinguished career, Dawoud Bey has used his camera to document his surroundings, looking closely at people as well as the places they live. Interested in the natural, social and political landscape, Bey has made multiple series that trace a lineage from past to present. This exhibition provides a chronology via selected images from 1976–2019, beginning with the series “Harlem, U.S.A.” (black-and-white photographs Bey shot in between 1975 and 1979) and concluding with the 2019 series, “In This Here Place,” which features eerie and haunting large-scale black-and-white images taken on plantations in Louisiana. Aiming to preserve African-American history and culture through photography, Bey also captures specific moments in time as a celebration of life. Shot on the streets of Harlem with a 35mm camera when Bey was 22 years old, the 10 images from “Harlem, U.S.A.” portray groups and individuals going about their lives: Some are aware of Bey’s presence, while others are not. The viewer’s eye dances across the composition of Four Children at Lenox Avenue (1977), which depicts four formally dressed schoolchildren caught in mid-action as they pause on the sidewalk.

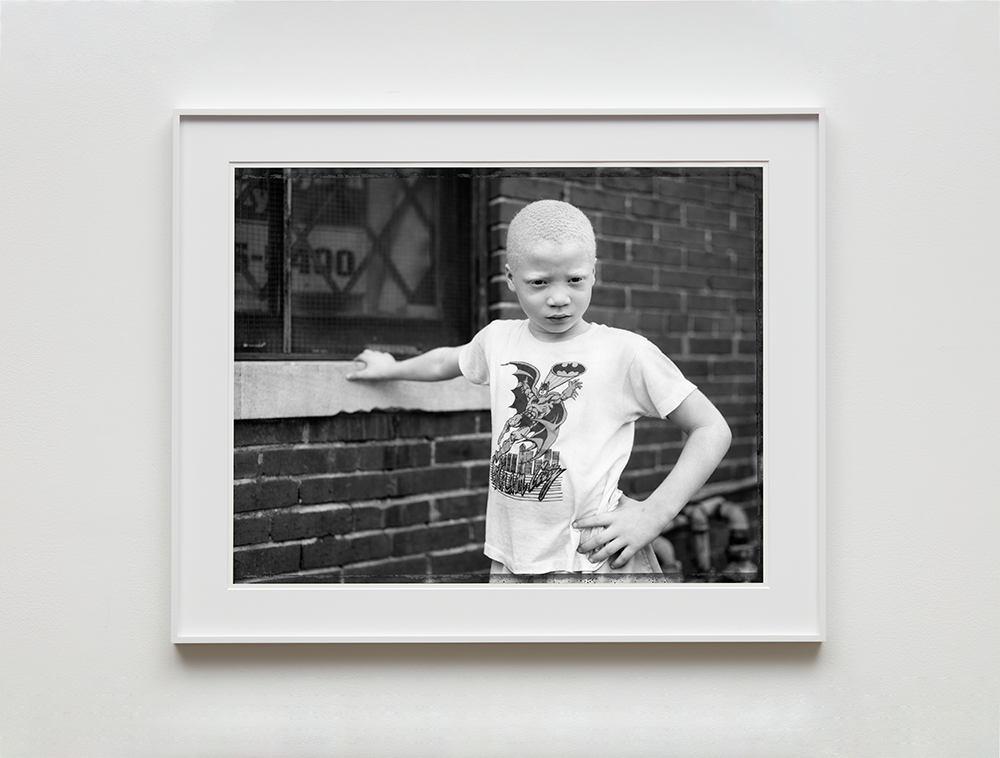

Shot on the fly, these photographs successfully capture the daily goings-on of the neighborhood, whereas his street portraits, shot 10 years later, convey more confidence, seemingly the result of more direct interactions with his subjects. With the later series, Bey’s aim was to create a studio in the streets, which allowed him to forge a relationship with his subjects (even if it was only for the duration of the shot). For example, Buck (1989) presents a young boy wearing a Batman T-shirt posed against a brick wall, his stance aggressive, self-assured and vulnerable.

Dawoud Bey, Picket Fence, Tree, and Cabin, 2019. © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy of Sean Kelly.

Bey returned to the streets of Harlem in 2014 to create “Harlem Redux,” a series that documents the beginnings of gentrification and economic changes in the neighborhood. Harlem has become a different place, and through his photographs, Bey tracks these shifts. In Patisserie (2014), a white man using his laptop is juxtaposed with a Black woman working behind the counter of an upscale bakery. Young Man, West 127th Street (2015) documents a construction zone where a figure wearing a hoodie stands before a prominent No Entry sign. Clothes and Bag for Sale (2016) shows clothing hanging on a chain-link fence, laying on the sidewalk atop blue tarps that obstruct the view of a vacant lot. The absent people, represented by the hats, jackets and shoes, allude to ongoing displacement.

The timeline ends with examples from two recent series: “In This Here Place,” composed of photographs of plantations, and “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” which features dark, unspectacular landscapes shot at night. According to Bey, the works “imagine the flight of slaves along the underground railroad racing toward freedom,” evoking the history of injustices toward the African-American community. Without being overly didactic, Bey poetically invites audiences to contemplate the past and its relationship to the present moment.