“I trust in the intelligence of the audience,” says artist and filmmaker David Shapiro, whose elliptical, complex documentary film, Missing People, had its debut screening at Toronto’s Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival in April and will have its U.S. premiere (June 12 and June 14, see times and locale below) at Los Angeles Film Festival. A complex double narrative centered on the unlikely interweaving of the lives of complete strangers—of which the catalyst is the work of a self-taught artist little known outside his native New Orleans—the film is rich with ideas about art, love, truth, and the quest for self-knowledge. The film’s sweeping themes and emotional directness belie its subtle interplay of personalities, histories, motivations and consequences. “Ultimately,” the filmmaker asserts, “this is the kind of film the audience completes.”

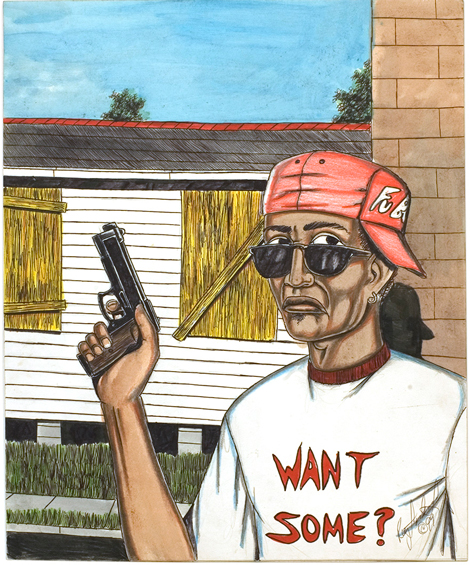

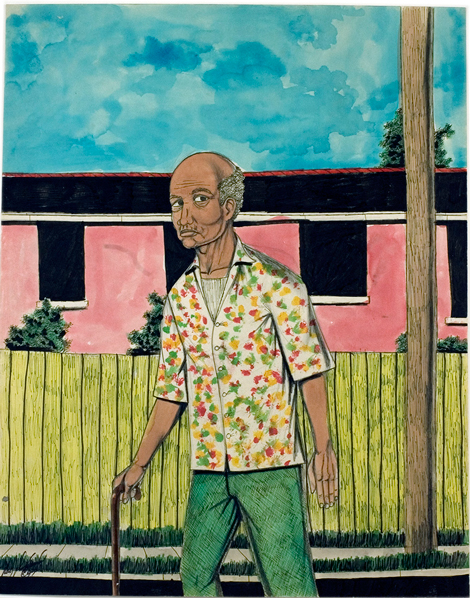

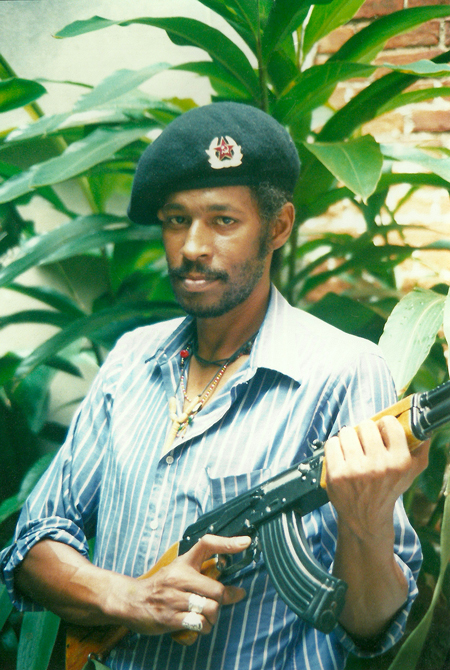

In 2010, Shapiro (Keep the River On Your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale, 2000) began discussions with collector and Ronald Feldman Gallery director Martina Batan about making a film on the art and life of Roy Ferdinand, who died in 2004 at the age of 45. Before long, Martina’s curious obsession with Roy’s blunt depictions of street violence and its aftermath—her evident desire “to glean meaning from Roy’s art”—became Shapiro’s focus and the dark heart of this beautiful, devastating film. Missing People begins as a character study, and slowly pries itself apart to become a layered meditation on class, race, economic disparity, social stratification and dysfunctional family dynamics.

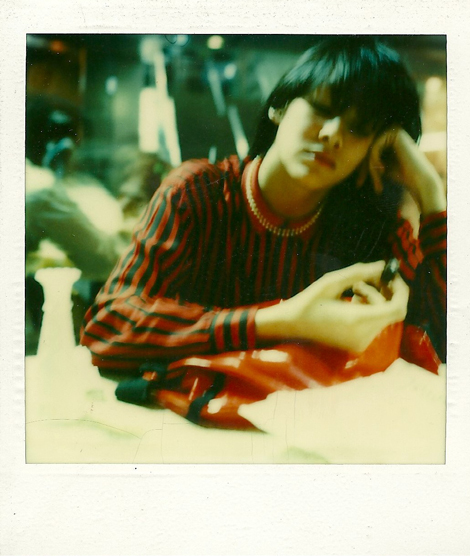

Martina is an insomniac, haunted by the memory of her beloved younger brother Jeff’s horrendous, unsolved murder when he was 14-years-old. A childhood friend, the artist David Carrino, theorizes that Martina gravitated to the top tier of the New York gallery scene in an effort to transcend her working-class roots in Rego Park, Queens by reinventing herself as a smoothly glamorous professional. There may be much more to it: Jeff seems to be the one thing from Martina’s former life that she won’t—or can’t—allow herself to lose.

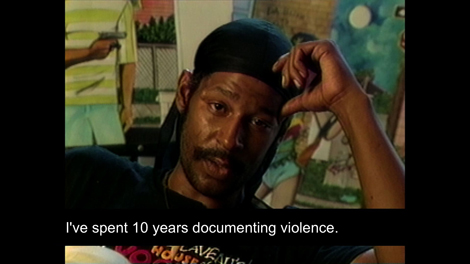

Roy is brought vividly to life through videotaped interviews and the reminiscences (both fond and otherwise) of his sisters, Faye Harris and Michele Ferdinand, whom Martina meets with in New Orleans. The women share a premature loss of a brother, but their real bond is formed as they puzzle over the place of Roy’s art in the wider world. Shapiro, whose work in drawing, sculpture and installation has been exhibited frequently in New York and elsewhere, takes a long view of the art distribution system. Among the ancillary issues the film raises, he says, are “who’s ‘inside’ and who’s ‘outside’? Who decides what art becomes valuable, and when? How does that value remain intact?”

The dawning significance, for Martina, of the correspondences between Roy’s work and Jeff’s death leads her to hire a private investigator to look into the circumstances of her brother’s grisly demise. The film honors Martina’s dogged but provisional attempts to connect the dots by not telegraphing any easy answers, instead allowing questions to slowly bubble up to the surface—as when we learn that Roy’s drawings function as documents of pre-Katrina New Orleans, of architecture no longer extant, of people no longer alive.

“I believe in exposing—or at least acknowledging—the apparatus of the filmmaking,” says the director, who operates not in the fly-on-the-wall manner of ‘direct cinema’ practitioners, but rather uses the textures and techniques of fiction film—establishing shots, program music, rigorous editing, and the like—to arrive at an “emotional truth” in cinematic terms. Unforeseen events essentially rewrote the film’s conclusion, and cast doubts on Martina’s chances of achieving any resolution. “Sometimes life forces your hand,” Shapiro says, who resorted to shooting the final scene on his cellphone.

Eventually, the adjective in the film’s title resonates as a verb as well. In a video clip toward the end of the film, Roy (whom the viewer knows from taped interviews) asserts, “If it wasn’t for what I do, nobody would ever know these people existed… One of the important things in life is for somebody to acknowledge that you’re there.”

Screenings at LA Film Festival

FYI: Faye and Michele, Roy’s sisters, will be in attendance at both LAFF screenings:

Friday, June 12, 8:45PM: Regal Cinemas L.A. LIVE

Sunday, June 14, 8:55PM, Regal Cinemas L.A. LIVE

Tickets: http://bit.ly/missingpeoplelaff

Films website:

www.missingpeoplefilm.com

Missing People

Written and Directed by David Shapiro

Produced by Alan Oxman, David Shapiro and Michael Tubbs

A DoubleParked Pictures production

Running time: 81 min.

(color, HD)