Showcasing appropriated images of young girls alongside pornography from niche fetish websites in her daring mixed-media works, Darja Bajagic’s solo exhibition offers “Cold Comfort,” as the show’s title so aptly indicates. The recent Yale MFA grad stirred controversy in the halls of that venerated school for her work’s seemingly apolitical stance on this taboo. Accused of irresponsibly promulgating pornography instead of steering away from it, Bajagic compels the viewer to confront the societal proscription of her subject matter.

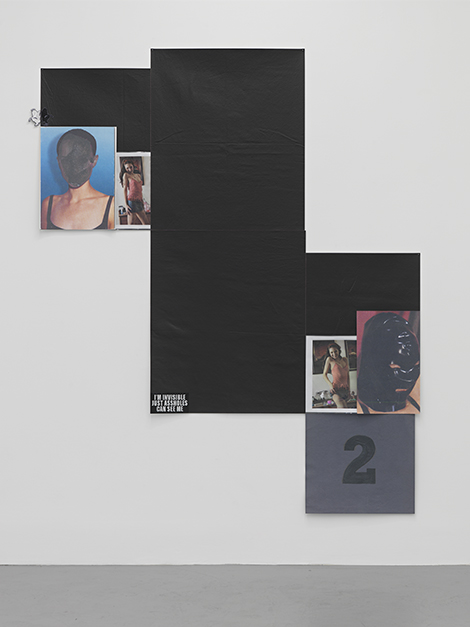

Darja Bajagic, I’m Invisible Just Assholes Can See Me, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist and ROOM EAST.

In You Should Hear the Names the Voices In My Head Are Calling You (2014), a picture of a young girl, her mouth wide open, stares mockingly at the viewer. Diagonally opposite, a smaller porn image of a topless woman holding a dildo between her breasts looks on seductively. The word “brat,” which refers to a ’90s zine that voiced a critical youth perspective on politics and culture, emblazons the asymmetrical black canvas panels affixed with these lurid images of youth and the sex trade and upends our assumptions about female sexuality.

Similarly, in Come To The Dark Side We Have Cookies (2014), a provocative picture of a woman is mostly concealed behind black canvas flaps that can be raised to reveal the entire image. This element of furtiveness, derived from the flaps, recalls the secrecy of peep shows in the ’70s and suggests the forbidding and darker side of the sex trade, just as much as the invisible faces covered by a black scarf and ski mask hint at danger and violence in I’m Invisible Just Assholes Can See Me (2014). These images of sexual innuendo are juxtaposed with pictures of debonair young girls in camisoles reminiscent of an

underaged Nabokovian Lolita. Bajagic’s deliberate combination of innocence and carnal allure points to her larger concern about the objectification of the female body.

Darja Bajagic, Come To The Dark Side We Have Cookies!!! (detail) (2014). Image courtesy of the artist and ROOM EAST.

Yet her union of spare black canvases with sensational female images removed from their original context highlights Bajagic’s strategy to neutralize and desexualize pornography. Empowered by their ability to look the viewer in the eye, these commodified women are presented in a new light. Their gaze is directed at the perpetrator, whose prurient interest is met from a position of refusal and mockery. By entering a previously male domain, Bajagic situates her work outside the voyeuristic concern. And by employing shocking and unsettling captions, she allows the viewer to accept the severity of the imagery and cue its interpretation.

Unlike the painter Sue Williams, whose cartoonish imagery often subdued the sexual violence she was confronting, Bajagic’s female figures bring our attention closer to the discomfort of her mission. Not always aesthetically pleasing or easily acceptable, her work has the strength of creating a new place for the ostracized other, and chips away at preconceived notions of taboo.

Ultimately, Bajagic’s own experience as the outsider—from her birth in Montenegro, upbringing in Egypt, and emigration to the U.S. at the age of nine—places her in a strong position to rebut instead of accept social alienation for herself as much as for the deprecated women she champions.