Even under the crowded, frenzied conditions of a gallery opening, where you know collectors, other artists (and additionally, professional photographers in this instance), the usual Hollywood smattering of celebrities, supermodels and beautiful people, and die-hard enthusiasts are bound to throng, it is impossible to emerge unmoved or unaffected from an exhibition of work by Ruven Afanador. That a still photograph should pulsate with rhythm and movement may seem like a contradiction; but with Afanador, it’s the sine qua non and personal signature. A gallery of such photographs is nothing less than a full-blown ballet, a farandole, a fandango – more specifically here, the flamenco, which beyond its Romani/gitano roots and the Spanish-Moorish culture of the Andalusian region, comprehends an entire culture and sensibility. Afanador has visited this region and culture before (in Mil Besos – an exhibition and book which was also mounted as a show at Fahey/Klein); and to some extent, you see (and feel) its influence in other bodies of work. But I don’t think he has ever come as close to the pulsating heart, the full àngel, if you will, of the culture, as in this show, Àngel Gitano – The Men of Flamenco.

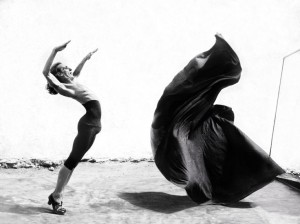

Afanador has a passion for theatricality just barely held in check by a certain geometric elegance and compositional rigor. There is something of Herb Ritts in the sheer graphic choreography of dense, contrasting black and white, the geometrics pared down to elegant gesture and bathed under diffuse light; but more importantly something entirely his own – a sensibility akin to the cinema of Almodovar, Bertolucci or Buñuel, even perhaps some of the dancers and theatrical artists photographed here. We certainly saw this in Mil Besos, which focused on the women of the flamenco – with their larger-than-life silhouettes (and ornaments), their towering coiffures, super-sized fans and accessories, their operatic maquillage, gestures and expression. You don’t need a full black or crimson satin cape for an Afanador portrait – but it doesn’t hurt. It hardly matters either way, the intensity of the pose, the moment, the subject (or the subject’s identity), the photographer’s gaze itself internalizing, crystallizing that ‘cape.’

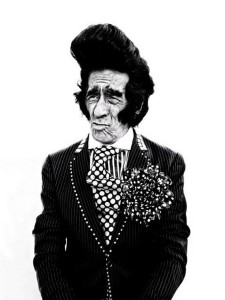

I could go through the exhibition picture by picture – they’re all mesmerizing – but consider, for example, the portrait of Miguel Flores, “El Capullo de Jerez,” (which as far as I can make out, translates to ‘the Cocoon of Jerez’ – which may refer to his seemingly cantilevered and towering pompadour – an ancient dandy, impossible to caricature, whose pattern-against-pattern shirt and tie, striped jacket with whipstitched lapels and exploding corsage just manage to contend with the wrinkled features, lush eyebrows and sardonic expression of his face. Or consider a formation of dancers arrayed as if to form a crown or a nest; or another resembling a scorpion. A corseted (or cummerbunded?) toreador conjures a black cape into an unfurling tornado. A portrait of Rubén Toledo turns its subject to the whorl at the center of a storm, a hurricane in human form thrusting his oversized mitts to the sky – an arabesque of human will, capacity, and ambition. Or consider some of the dwarf performers – a living link between ancient traditions of dwarf jesters to the nobility, gypsy entertainments and even vaudeville.

It’s all here: the surreal theatricality and pictorial sweep, the stark geometries in exuberant, extravagant motion, the glamour, the ritual and hieratic mystery, the pathos, the passion, the animalism, the flamboyance, the corruption, the tragic enigma and absurd comedy of human life on this nearly destroyed planet. It feels as if you could gaze for hours, live a lifetime, with each photograph, but the show moves with some velocity, sweeping us up and flicking us out the door as easily as that ‘scorpion’s tail’ might – and with a similar but irresistible sting.