It is that most fundamental of human needs – our need to make sense of things, to report, describe and explain the world; which itself may be at the core of our social and cultural needs, perhaps the basis of society and culture – the need to bring order to our lives and surroundings. Setting aside those scientific and mathematical giants and singular artistic geniuses of antiquity and the Renaissance, we see the first real shift in consciousness resonating across states and societies with the Enlightenment. On the shoulders of those giants, rigorous observation and analysis, scientific method and classification redefine old orders – or overturn them altogether. Ever more refined instruments amplify old and uncover the new. As the New World’s social engineers produce a constitutional republic and the Old World’s mechanical engineers give us the steam engine, yet another shift is in order.

And soon enough there we are with our rulers, scales and measurements, those instruments and engines – that Steve McPherson left us with in Part 1 of this post, configured into that archaeologized index of a measureless will to measure, control, move and extend our reach into the world. With industrialisation comes another order of rationalization – of resources, production, economies – the impact of which is also felt across culture and society. We see the multiplied benefits, but also the costs. In the meantime, Darwin underscores the brutal struggles underlying our ascent to stewardship, while Malthus alerts us to its harsh limits – abundance for some may mean scarcity for others.

Flatirons for Shoe Manufacture; Albert Renger-Patzsch, German, 1897 – 1966; about 1926; Gelatin silver; Sheet: 22.9 x 16.8 cm (9 x 6 5/8 in.); 84.XM.138.1

Each fresh wave of industrialisation and the technological advances and refinements that accompanied them brought fresh disillusionments with the domain of machines; but World War I took that disillusionment to another level entirely. Europeans began to see not merely a warfare amplified by machinery and mechanization, but the entire business of war as a killing machine with its own integral logic and inexorable momentum. The Weimar Republic that emerged in the Great War’s aftermath coincided both with a fresh maturity of the industrialized urban state and society and a magnified awareness of its potential benefits and potentially lethal undercurrents. Europe had already seen this shift in consciousness: in art, by way of early Dada manifestations (both in Zurich and Berlin; e.g., Schwitters); through contact with American machine-obsessed culture; but also in philosophy (e.g., the phenomenology of Husserl, especially as he anticipates (and directly influences) Heidegger and later philosophers). Coupled with this shift is a change in attitude – what became known as the neue Sachlichkeit, or new Objectivity (though I prefer an alternative translation of ‘matter-of-fact-ness,’ since this is what consistently comes across in so much of the art that falls into this category). The term was proposed fairly early in the evolution of what amounts to an attitude and approach to art-making, rather than a consistent school or style, by (naturally) the German art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub. It is this shift in attitude that LACMA curator Stephanie Barron has made the subject of a comprehensive (filling the entire second floor of LACMA’s BCAM) and frequently breathtaking exhibition.  Expressionism doesn’t entirely vanish; and there’s certainly a continuity with Expressionism’s graphic and self-consciously satiric strains. But the self-consciousness with respect to both medium and subject is more often muted in favor of the flattened mark and the frank, dispassionate gaze. There’s no need to draw attention to expression, per se. It just ‘is what it is.’ Barron organizes the exhibition around the subjects that comprise the varied objects of this gaze – what amounts to the fabric of life in Weimar Republic Germany. For all its ‘matter-of-factness, this is never particularly ‘random.’ The focus never ‘falls’ here, but is firmly, unflinchingly fixed, its objects thoroughly scrutinized. Exemplifying the modern 20th century urban industrialized society as Weimar did, the life of the city itself – from streets to factories to commercial life and entertainment and nightlife – became a prominent subject in the hands of Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Georg Grosz and many others. Conversely, the relationship with a formerly agrarian society and nature itself comes in for reexamination in both painting and photography (e.g., Georg Scholz and Georg Schrimpf). In Germany, as in America, the industrial metropolis gave rise to a prosperous merchant class which, along with the newly emergent bourgeoisie, was highly visible in the life of Berlin and other cities. By contrast, the displaced, disabled and otherwise disenfranchised of this society came in for another kind of scrutiny altogether.

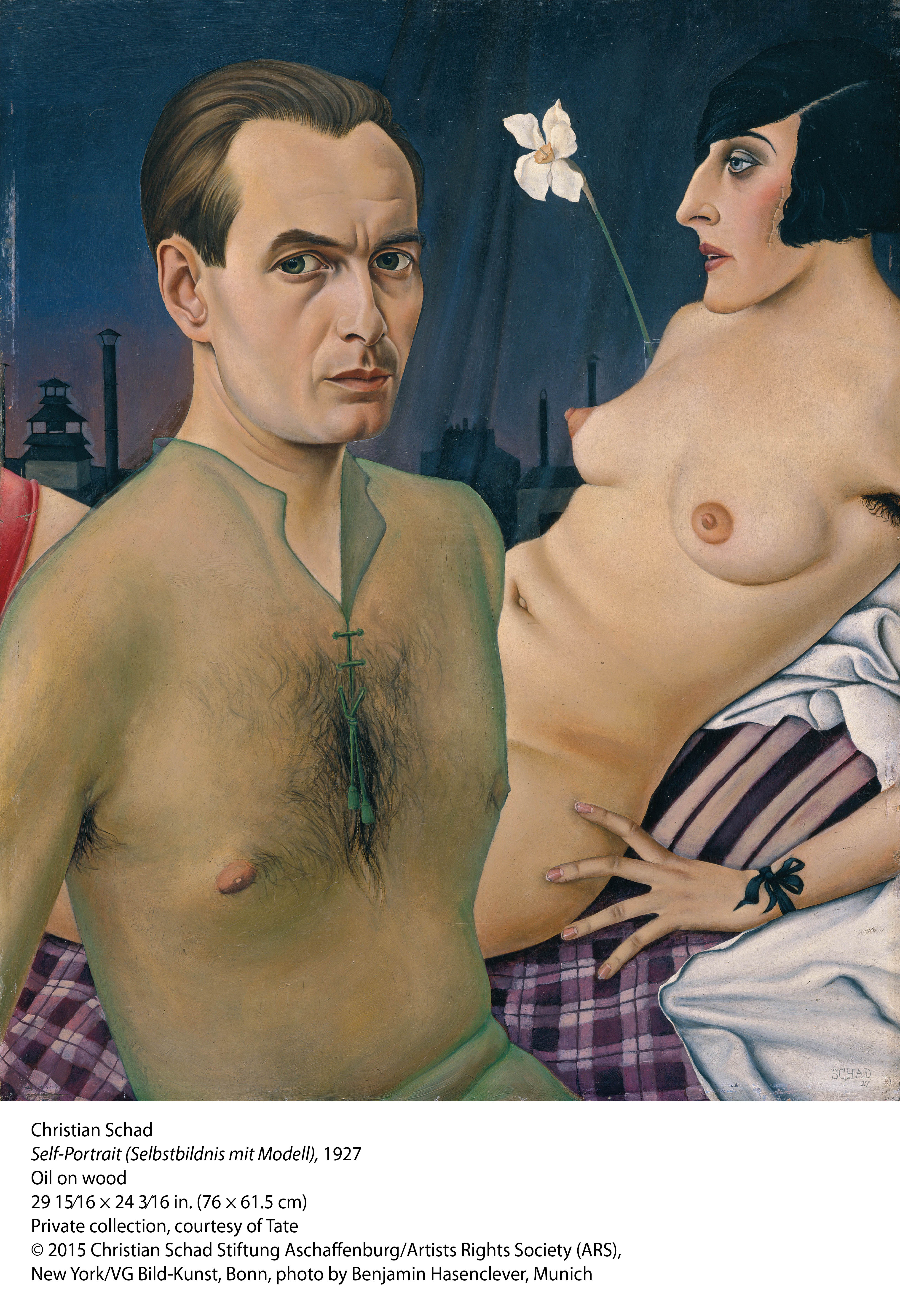

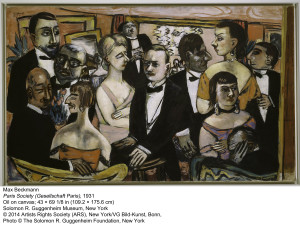

Expressionism doesn’t entirely vanish; and there’s certainly a continuity with Expressionism’s graphic and self-consciously satiric strains. But the self-consciousness with respect to both medium and subject is more often muted in favor of the flattened mark and the frank, dispassionate gaze. There’s no need to draw attention to expression, per se. It just ‘is what it is.’ Barron organizes the exhibition around the subjects that comprise the varied objects of this gaze – what amounts to the fabric of life in Weimar Republic Germany. For all its ‘matter-of-factness, this is never particularly ‘random.’ The focus never ‘falls’ here, but is firmly, unflinchingly fixed, its objects thoroughly scrutinized. Exemplifying the modern 20th century urban industrialized society as Weimar did, the life of the city itself – from streets to factories to commercial life and entertainment and nightlife – became a prominent subject in the hands of Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Georg Grosz and many others. Conversely, the relationship with a formerly agrarian society and nature itself comes in for reexamination in both painting and photography (e.g., Georg Scholz and Georg Schrimpf). In Germany, as in America, the industrial metropolis gave rise to a prosperous merchant class which, along with the newly emergent bourgeoisie, was highly visible in the life of Berlin and other cities. By contrast, the displaced, disabled and otherwise disenfranchised of this society came in for another kind of scrutiny altogether.  Class may be the operative word here. Barron gives some emphasis in this exhibition to the shift in attitudes towards individual identities, including children’s. Portraiture probes character without necessarily piercing any veils (again, ‘what you see is what you get’); but presentation itself becomes a social and psychological narrative of the subject’s relationship with both self and society. We see this acutely in Beckmann and Christian Schad, but in many others, too (Dix, Ploberger, etc.). August Sander takes up the project as an entire body of work, the People of the Twentieth Century.

Class may be the operative word here. Barron gives some emphasis in this exhibition to the shift in attitudes towards individual identities, including children’s. Portraiture probes character without necessarily piercing any veils (again, ‘what you see is what you get’); but presentation itself becomes a social and psychological narrative of the subject’s relationship with both self and society. We see this acutely in Beckmann and Christian Schad, but in many others, too (Dix, Ploberger, etc.). August Sander takes up the project as an entire body of work, the People of the Twentieth Century.  Sex may be another such word – and you almost have to assume it had something to do with a need to escape the domain of the machine. Depictions of Lustmord or sex murder are luridly graphic. But Weimar artists also confront sexual and gender identity and orientation with a fresh candor. Setting aside how the art was originally received, so many of these portraits have a striking coolness. ‘Here we are – it’s no big deal.’

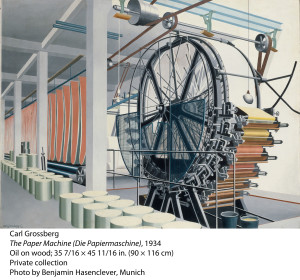

Sex may be another such word – and you almost have to assume it had something to do with a need to escape the domain of the machine. Depictions of Lustmord or sex murder are luridly graphic. But Weimar artists also confront sexual and gender identity and orientation with a fresh candor. Setting aside how the art was originally received, so many of these portraits have a striking coolness. ‘Here we are – it’s no big deal.’  The Industrial Age’s fascination with the machine, its speed, functional efficiency, precision and refinement, endured. Machines and the products of industrial manufacture are prominently featured in this art (e.g., Carl Grossberg, Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski, Hans Finsler). But there is another fascination at work here – the notion of an integrated totality, ‘greater than the sum of its parts,’ functioning almost as an organism – and by extension, a potentially more rational view of the way cultures and societies are formed and function. It was no accident that the Bauhaus, with its embrace of the machine aesthetic, blossomed during the Weimar Republic But certainly the opposite impulses are also encompassed here – alienation, distrust, an implied deconstruction, itself on a continuum with work seen earlier in the century. And the beat goes on. In this way, the New Objectivity show holds up a mirror to the urban society of our own age transformed by digital technology into what is both a well-oiled (in every sense – including digital apps) computer and, despite the omni-presence of vast virtual social networks, a fraught and alienating environment. We are seeing the emergence of a new bourgeoisie of venture capitalists, digital technocrats and wizards; but also the displacement of many who are not easily reoriented within the digital landscape. We are casual about sex, but also a good deal cooler; maybe even cold. (‘That was excellent. Please don’t be here when I wake up.’) As the planetary biosphere collapses, all life starts to look exotic. The “Gyres run on” in our time. The artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit cast the same ‘cold eye’ on flesh as they did on steel; in the 21st century, we’re finally learning (a bit too late) to cast that cold eye on life and death.

The Industrial Age’s fascination with the machine, its speed, functional efficiency, precision and refinement, endured. Machines and the products of industrial manufacture are prominently featured in this art (e.g., Carl Grossberg, Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski, Hans Finsler). But there is another fascination at work here – the notion of an integrated totality, ‘greater than the sum of its parts,’ functioning almost as an organism – and by extension, a potentially more rational view of the way cultures and societies are formed and function. It was no accident that the Bauhaus, with its embrace of the machine aesthetic, blossomed during the Weimar Republic But certainly the opposite impulses are also encompassed here – alienation, distrust, an implied deconstruction, itself on a continuum with work seen earlier in the century. And the beat goes on. In this way, the New Objectivity show holds up a mirror to the urban society of our own age transformed by digital technology into what is both a well-oiled (in every sense – including digital apps) computer and, despite the omni-presence of vast virtual social networks, a fraught and alienating environment. We are seeing the emergence of a new bourgeoisie of venture capitalists, digital technocrats and wizards; but also the displacement of many who are not easily reoriented within the digital landscape. We are casual about sex, but also a good deal cooler; maybe even cold. (‘That was excellent. Please don’t be here when I wake up.’) As the planetary biosphere collapses, all life starts to look exotic. The “Gyres run on” in our time. The artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit cast the same ‘cold eye’ on flesh as they did on steel; in the 21st century, we’re finally learning (a bit too late) to cast that cold eye on life and death.