LACMA’s “In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art,” (through Sept. 9) starts with a gallery devoted to Siamak Filizadeh’s digital print series “Underground.” This modern-day retelling of the reign of Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96) begins with “Coronation:” the hearty-mustached king grips a rabbit upon a throne (his legs–clad in red panty hose—allude to al-Din’s infamous harem). Suggesting the Herat-style illustration of 15th-century Persian manuscripts, the shah is bordered by eight domes, each inhabited by various players in al-Din’s history—including Mirza Reza Kermani, the shah’s eventual assassin.

None of this information is provided. Curator Linda Komaroff decided to mostly forgo didactics for the show’s 125 photographs, paintings, sculptures, installations and animations. “Empty Days” also rejects a linear chronology, which made me imagine the exhibition’s layout as a nautilus shell, a circular world where past and present constantly rub against each other.

The show has been criticized for its lack of explanatory didactics. But I think this lacuna is the point. I think the show is as much about the visitors’ history as Iran’s.

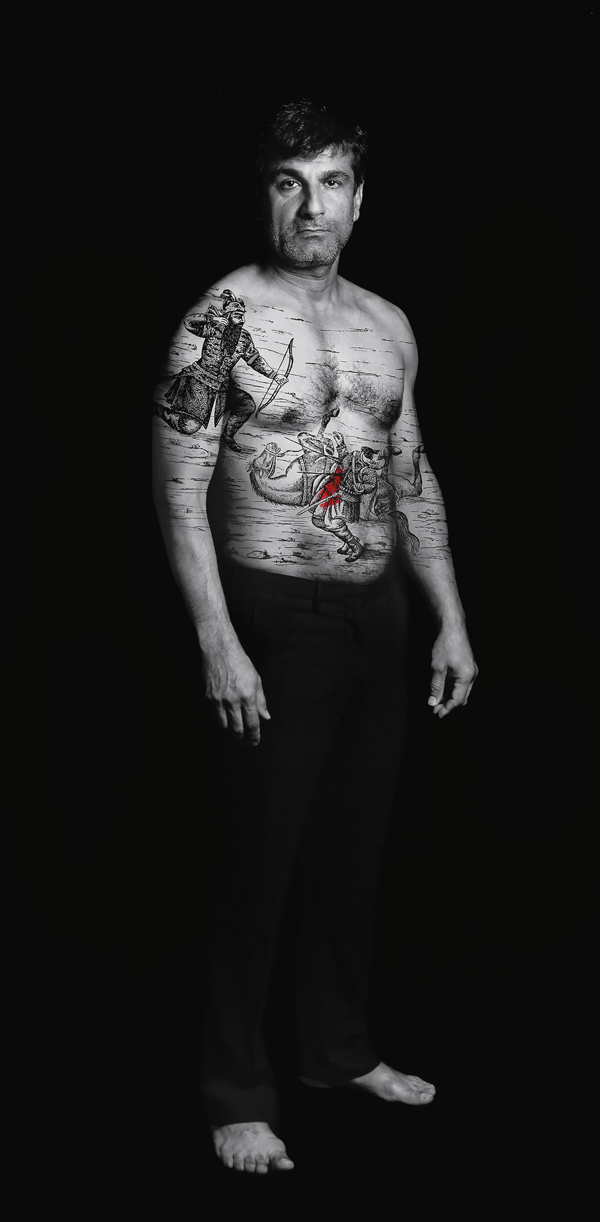

In her photo series “The Book of Kings,” Shirin Neshat takes lithographs from Iranian national epic “Shahnameh” and literally projects them onto shirtless Iranian men—saying Iranians are “tattooed” with a historical, nationalistic identity. This is clear.

Shirin Neshat, Amir (Villains) from the series The Book of Kings, 2012, © Shirin Neshat, photo courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Less clear is Shoja Azari’s “Icons” series: five light-box posters of Iranian women dressed in classic Persian attire. Admiring the static images, you’re taken aback when the subjects suddenly blink. These are video portraits. And they’re beautiful—regardless of whether you’re aware they’re based on a form of poster once popular (now banned) in Iran that illustrated Shi’ite saints. (Icon #1, for example, depicts a female warrior holding a bifurcated sword while kneeling behind a lion—a riff on the nearly identical poster of Muhammad’s son-in-law, Ali.)

While visiting the exhibition, someone asked if I’d heard of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. I tried explaining how the museum itself is the artwork. I felt the same about “Empty Days.” Komaroff said, “This show is about an art that willfully blends time and obscures place.” Even without knowing Iran’s past, this thesis is obvious. And the artists in the show clearly know their history.

But as in the case of the U.S. assisting to re-empower the shah in 1953, and backing him through his ouster in the 1979 Iranian Revolution, or America’s recent tensions with Tehran over nuclear issues, it seems our elected officials rarely understand the history or people of the nations with which we engage. Americans enter the fields of war without knowing the country’s history. Americans enter the “Fields of Empty Days” without knowing Iran’s history.

Traveling through the nautilus—past the exhibition catalog that explains everything—the final piece is a white tent with heartbreaking cartoons projected on its rounded walls. Its title: Mourn Baby Mourn.

0 Comments