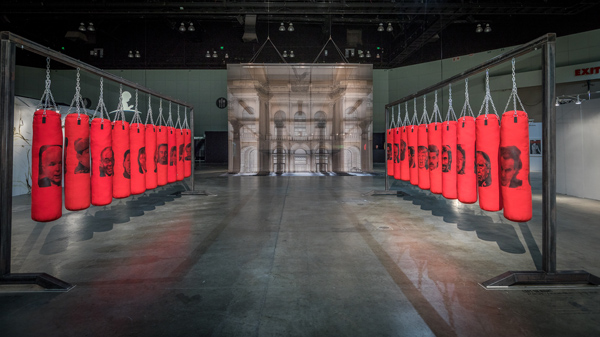

In September 2017, the Los Angeles Times ran the headline “Four must-see art shows that speak to the anxiety triggered by Trump’s DACA reversal.” In November, HuffPo posted “A Guide To The Anti-Trump Art You Can See In New York Right Now.” In January 2018, one of the most crowd-pleasing pieces in the Los Angeles art fair, LA Art Show, was “Left or Right”: 20 red punching bags, each bearing the face of a controversial world leader—you can guess the most popular face to sock. At the same time attendees were left-hooking Trump, one could type “anti trump art” in Etsy and return 1,649 results. Search “pro-trump art” and you’ll receive 100 results—18 of which are actually pro-45.

Given the ideologies (and finances) of many artists, the surfeit of anti-Trump exhibitions isn’t surprising. My question is this: If Rembrandt painted a portrait of Trump, would you be able to appreciate it?

At “Daddy Will Save Us”—touted (by Breitbart) as “the first pro-Trump art show”—one of the signature pieces was a neoclassical painting of George Washington donning a Make American Great Again hat. It doesn’t take much mental stretching to imagine Mr. Brainwash wheatpostering Hitler wearing a MAGA hat (and, p.s., that piece, though not by Brainwash, appeared in a Portland bar).

Is a work “great” because you agree with it, or because it’s “good art”? It seems there have been exceptions; staying on Hitler for a moment, Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will is still considered a technological—and propagandist—masterpiece.

Perhaps the bigger question is whether overtly political pieces are art or political statement.

Was Shepard Fairey’s “HOPE” art? I’d say “no,”

but it’s for reasons completely different than why a Syrian child whose home was bombed by one of the Obama administration’s drones might answer “la.”

The question may have been answered best by Jon Naar, who documented New York graffiti in its earliest of days. Naar, who provided photographs for Norman Mailer’s The Faith of Graffiti, said: “Graffiti for me has always been a political act first, and then art second; it is always a political act.”

I think the visual triage is important; whether, when first coming across a work, you see it as art or as politics. Consider Judy Chicago’s feminist-art installation The Dinner Party—a triangular table with 39 place settings, each commemorating an important woman from history. Does it only belong in the Brooklyn Museum if you support the feminist cause? The Dinner Party, I think, is seen as art first, political act second.

Maybe great political art—to become great—has to transcend its political message. Picasso’s Guernica was a response to the bombing of said city by Nazi Germany at the request of Spanish Nationalists. Whether or not you know the painting’s historical impetus, it’s a powerful piece: It received a gold medal at the 1935 Venice Biennale and the Grand Prix at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris.

It didn’t. Triumph Of The Will won those prizes.