Just as there is a certain metaphysical link between acknowledging one’s existence and looking in the mirror, there exists a similar link between the acknowledgement of a culture’s experienced reality and its representation in media.

When a cultural group lacks representation, the variety of their experiences is suppressed. At times, then, they are fueled to create an artistic response outside of the conventional hegemony. Chicano artists throughout the movement of the 1960s and beyond are known for doing just that through public artworks. What are the implications, then, when those self-created representations are erased?

¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes documents the life, and inevitable death (or purgatory in one case) of eight murals created by Mexican-American artists throughout LA. The exhibition is different from any I had ever been to, most notably because none of the works actually exist anymore. What is on display is a re-assemblage of parts that remained of the murals, including photographs, preliminary sketches, paintings and pieces of rubble. These scraps are relied on to give the viewer an idea of what the murals were like when they were on public view.

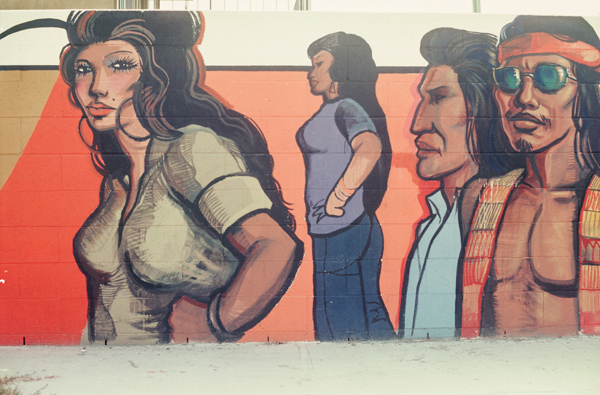

details from Sergio O’Cadiz’ Moctezuma, Fountain Valley Mural, 1974–76; destroyed 2001; Calle Zaragoza, Colonia Juarez, Fountain Valley.

The archival care given to the remaining fragments greatly contrasts with the flippant actions of their destroyers. Viewers have the chance to catch a rare glimpse into the ghosts of these past murals. Many of the pieces, such as reference photos of people within the finished works, humanize and give context to the murals.

Censorship is a major thread present throughout the exhibition. Many of the murals were commissioned and approved by institutions, only to be deemed too controversial after their completion. It seemed that institutions and the public at large felt discomfort when viewing the uncomfortable reality of Chicano life and history. Sergio O’Cadiz Moctezuma’s Fountain Valley Mural (1974) was initially censored before it was inevitably destroyed. The mural, which consisted of various Chicano portraits, depicted what appears to be a young Chicano man being dragged away by police officers. The violent section was spray-painted white to block sensitive viewers from having to face what was, and is to this day, a fairly common scene.

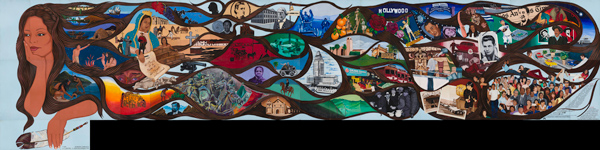

Barbara Carrasco, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective, 1981, censored 1981, Intended site: 330 South Broadway, Los Angeles.

Barbara Carrasco’s L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective (1982) was similarly deemed unfit for public view after being commissioned by Los Angeles’ Community Redevelopment Agency for the city’s bicentennial celebration. The work depicted the Zoot Suit Riots, the whitewashing of a mural by Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Dodger Stadium, which displaced thousands of Mexican-American landowners and families in the Chavez Ravine. The bicentennial decided to not allow Carrasco’s work due to these historical depictions. Carrasco, with the support of historians and community groups, petitioned to show the mural during the 1984 Olympic Games in LA, but the proposal was rejected.

One of the examples of whitewashing that I found most painful to stomach was that of Roberto Esteban Chavez’ The Path to Knowledge and the False University (1974) at East Los Angeles College (ELAC). The sprawling, brilliantly colored mural was painted along the side of the Rosco C. Ingalls auditorium. Above the mural was a plea to bring Chicano studies to the college. Five years later, the college president claimed the removal occurred because the auditorium needed repairs. Mysteriously, the only wall touched was Chavez’, leading to the widespread belief that the whitewashing was merely an attempt to discourage the Chicano movement at ELAC. Chavez later created The Execution (1982), a film which depicts a man being electrocuted and Chavez playing the part of the college administrator destroying a mural.

East Los Streetscapers (David Botello, Wayne Alaniz Healy, George Yepes), detail from Filling Up on Ancient Energies, 1980, destroyed 1988, acrylic on concrete, 1,200 square feet, corner of 4th and Soto Streets, Boyle Heights, Los Angeles.

Healy, Botello, and Yepes (left to right) complete Filling Up on Ancient Energies, 1980

Courtesy of East Los Streetscapers

Not all of these works were destroyed for political reasons, however. East Los Streetscapers’ Filling Up on Ancient Energies (1980), which depicted such colorful, apolitical images as dinosaurs and classic cars, was destroyed by Shell Oil through what can only be described as apathy. The company later lost a lawsuit to the Streetscapers, and laws were passed to bring murals under California’s protection. While the muralists created a victory for future artists, it’s impossible to ignore how much more history the community would have if the mural was still intact.

While the censorship, destruction and abandonment of these murals happened decades ago, it plays into a larger narrative about public expression of Chicano artists and the censorship and silencing of a culture. To this day, Chicano muralists are creating new murals in areas like Boyle Heights, where the community is actively fighting against gentrification, which, it can be argued, is one of the most powerful agents of censorship.

Roberto Chavez, The Path to Knowledge and the False University, 1974–1975, whitewashed 1979, East Los Angeles College, Monterey Park

While Chicano activists rally against developers to keep their roots in the neighborhood, artists continue the tradition of public art. Adrian Ulloa’s Love Our Mothers (2017) on the side of a Dollar store on Cesar E. Chavez Avenue depicts an indigenous woman with a powerful stare; perhaps she is Mother Earth, surrounded by butterflies, hummingbirds and nature. Nearby is Nani Chacon’s ¡RESISTE! (2017), in which two women touch hands in front of the earth and huge red lettering that says “RESIST.” One of the women wears a red bandana around her face—a piece of clothing emblematic of recent protests both in Boyle Heights and across the country.

While a select few murals of Chicano artists at LA Plaza are commemorated and others along a strip in Boyle Heights continue to be created, there are still many across Los Angeles that continue to vanish from lack of upkeep. In a time when public awareness of Chicano struggles—whether over displacement, police brutality or class struggle—has all but disappeared, public art continues to have a vital place in the streets and not just in the history books.

¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege

LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. Runs thru March 19, 2018