Do you ever wonder what happened to the Occupy moment? We can’t really call it a movement because it had no coherent program, plan or organization, no well defined or articulated policy (or revolutionary) objectives; and its only concrete target was a somewhat vaguely defined index of commercial and investment banks, securities brokerages, insurance exchanges, private equity and hedge funds. I’m not even sure if any of the principal instigators knew what they really wanted. Break-up of the ‘too-big-to-fail’ financial entities seemed to be pretty high on the agenda. But did anyone really have any clue how this might be accomplished in a political environment that had shifted from steady rightward drift into wholesale paralysis? (It’s as if our national governmental organizations have gone into deep freeze over the last several years or so in direct proportion to the planet’s climate warming – with similarly disastrous results.)

The vagueness of Occupy’s objectives, along with the complete absence of a rigorously programmatic, practical and truly radical agenda and strategy doomed the movement almost before the tents were cleared from Zucotti Park and (here in L.A.) the City Hall lawn. But the political psychology is pretty clear. We’re an occupied country here; and the essential changes that will be required are mostly not going to come from the existing political structures – nor from the private and corporate interests that are doing most of the occupying. The changes come from a community’s cultural life, which may reflect both Establishment and Dis-Establishment interests. The Los Angeles Opera has joined this ‘battle royal’ over the last couple of months with one lavish original production and two older productions spruced up and recharged by electric performances.

I don’t think L.A. audiences really needed much of an argument to interpose John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles in place of the actual third play in the Beaumarchais Figaro trilogy, La mère coupable (The Guilty Mother). Ghosts presents us with a visceral connection with the living tissues of history and inexorable ravages of time and physical forces beyond our control – and their resonance with the crises of the current historical moment. (There is in fact an opera based directly on La mère coupable by Darius Milhaud, with the libretto by his wife, Madeleine.) What I loved about the current production of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, which just opened this past Saturday evening, was an uncanny capacity, not merely to suggest the possibilities that unfold in La mère coupable, but to subtly articulate and underscore some of the unresolved conflicts both in the original Beaumarchais dramatic foundations and in the entire thematic notion of ‘Figaro Unbound.’

If there was ever a figure that defied the social and political boundaries of his time, it was the original Figaro himself, Beaumarchais. But, as Susanna and the Countess remind us in different ways through Mozart’s opera, such legerdemain is not so easily procured by the 99 percent (and still more emphatically, its feminine half). The current production is essentially the same production I saw in 2006 – with the same deliberately anachronistic set decoration and costuming. Whether or not (given the opera’s farcical parade of characters) an argument could be made for it, I found it creakily annoying the first time around. This time, I was happy to completely forget about it and could almost be amused by the Countess’s first appearance in her 1930s-ish bedroom with its 1950s-ish telephone. I’m as easily annoyed as ever (as readers of this blog are only too aware). The difference – for the entire production – can be summed up in three words: casting, choreography, and chemistry. The program credits the original director Ian Judge and choreographer, Sergio Trujillo, with additional credit given to choreographer Chad Everett Allen. I can’t pinpoint exactly where Allen has interposed changes to the characters’ movements and interactions; and there are a few moments where the stage blocking or character line-ups still seem a bit stiff – but whatever he changed or added and wherever he did it brought a fluidity and grace notably absent from the 2006 production.

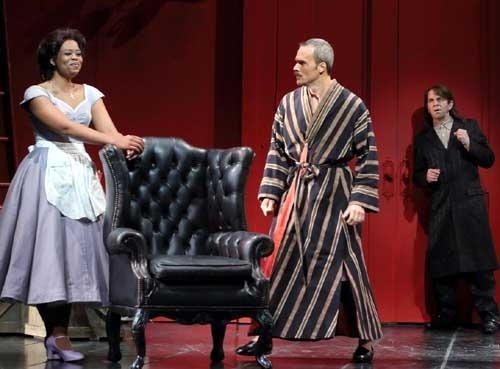

Did I mention the casting? It’s the old cliché of film and theatre direction and it applies no less here: the secret of good direction is great casting. The spotlight in recent weeks has been on the return of Pretty Yende to the L.A. Opera stage in the role of Susanna after her triumphs at the Met and Carnegie Hall – and she was great, though the role doesn’t really offer a scope in full measure with her vocal power. The surprise was that pretty much everyone in the cast rose to the same level. It was as if we were constantly echoing the Countess’s second act compliment to Cherubino, “Che bella voce.” Certainly that included the Countess herself, Guanqun Yu, whose exquisite voice shone through some difficult bedroom maneuvers (suggesting an aristo Maggie the Cat) in the same act and throughout the opera in what may be its most challenging role. Roberto Tagliavini (Figaro) and Ryan McKinney (the Count) were both commanding in their respective roles, a constant reminder of the power of great musicianship wedded to stage charisma.

The stage chemistry was particularly strong in scenes featuring Yende, Tagliavini, McKinney, and Yu; and the subtle emotional articulation was evident in their most brisk recitatives; the political implications of their dark double entendres foregrounded as much as the sexual. In various scenes throughout the opera, you felt a foreshadowing not only of Beaumarchais’ Guilty Mother, but so many other treatments of these themes and motives, from Strauss (e.g., Der Rosenkavalier) to Sondheim (A Little Night Music).

The Countess’s gracious magnanimity lights up the darker recesses (key to any staging of this opera) of Beaumarchais’ original farce. But even as the fireworks (live pyrotechnics in this staging) lit the characters’ way to the nuptial revelries, even as Figaro leaps away ‘unbound,’ we’re acutely aware of the chains (not just jewels) that keep these strong women tethered to their places. It’s far more explicitly underscored in the play in Susanna’s (or Suzanne’s) final speech:

Let a husband break his vows,

That’s from the John Wood (Penguin edition) translation, by the way. The original French is actually a bit more harsh. ‘Is it really necessary to question this absurd injustice? The stronger make their own law.’ They’re still making it. (It’s as if the entire point of their Congress is to not make any laws that complicate the economic ‘laws’ their financial maneuvers and machinations dictate.) “Se mi salvo da questa tempesta, / Piu non avvi naufragio per me,” Susanna and the Countess sing as they watch Figaro try to dodge the Count’s wrath in his mad third act jig on Cherubino’s behalf. “If I survive this storm / I’ll fear no further shipwreck.” Two hundred thirty years later, that sounds awfully familiar.