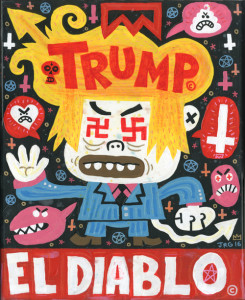

After a week that seemed to confirm everyone’s worst expectations for the planet, our dubious species, and its cratering political structures (to say nothing of crumbling infrastructure), it seemed almost miraculous to close on a note that, if it didn’t exactly diminish our pessimism, at least offered a few moments of joy. It can’t entirely compensate for the many substantive defeats we’ve collectively taken over the intervening years, but I was reminded that one war we’ve continued winning since the 1990s has been the cultural one. I won’t pretend to having any real hope for the American political system, but I’m sure I wasn’t alone leaving downtown with some assurance that the big orange not-terribly-presidential piñata we call Donald J. Trump, has lost the electoral race before his party has even confirmed his candidacy. After the border-busting delirium of “El First Solo Art Show de” Jorge R. Gutierrez at Gregorio Escalante Gallery and the trans-oceanic-cross-cultural romanticism of Mexrrissey at California Plaza, I was reminded that the culture had left him somewhere in the dust at least two decades ago.

After a week that seemed to confirm everyone’s worst expectations for the planet, our dubious species, and its cratering political structures (to say nothing of crumbling infrastructure), it seemed almost miraculous to close on a note that, if it didn’t exactly diminish our pessimism, at least offered a few moments of joy. It can’t entirely compensate for the many substantive defeats we’ve collectively taken over the intervening years, but I was reminded that one war we’ve continued winning since the 1990s has been the cultural one. I won’t pretend to having any real hope for the American political system, but I’m sure I wasn’t alone leaving downtown with some assurance that the big orange not-terribly-presidential piñata we call Donald J. Trump, has lost the electoral race before his party has even confirmed his candidacy. After the border-busting delirium of “El First Solo Art Show de” Jorge R. Gutierrez at Gregorio Escalante Gallery and the trans-oceanic-cross-cultural romanticism of Mexrrissey at California Plaza, I was reminded that the culture had left him somewhere in the dust at least two decades ago.

If it weren’t so hate-inspired, it would almost be hilarious. (‘You want to build a wall, Mr. Trump? Exactly how far norte do you want to build it? San Francisco?? Because we crave our Mexico here in L.A.’ To say nothing of the rest of the world. I almost wonder at this point how well Trump knows the island of Manhattan. He lives in a bubble.) If Trump were actually interested in expanding his political horizons, he might do well to spend some time in an actual border town – as opposed to those borders he’s more familiar with negotiating – the ones between solvency and bankruptcy (or possibly sanity and insanity).

If it weren’t so hate-inspired, it would almost be hilarious. (‘You want to build a wall, Mr. Trump? Exactly how far norte do you want to build it? San Francisco?? Because we crave our Mexico here in L.A.’ To say nothing of the rest of the world. I almost wonder at this point how well Trump knows the island of Manhattan. He lives in a bubble.) If Trump were actually interested in expanding his political horizons, he might do well to spend some time in an actual border town – as opposed to those borders he’s more familiar with negotiating – the ones between solvency and bankruptcy (or possibly sanity and insanity).

Jorge Gutierrez actually grew up on the U.S.-Mexico border, living with his family in Tijuana, but attending school in San Diego, and picking up and unpacking the cultural baggage both coming and going. One can imagine the stresses entailed by that constant cross-border commute; but through it all, Gutierrez kept his eyes wide open and imagination running at full-tilt. He was becoming a bricoleur of pop cultural iconography probably before he even knew he wanted to become an artist. But it’s a phenomenon that almost anyone who grew up in the late 20th century or later can appreciate because we all grew up in a kind of pop culture bricolage fashioned out of our variable circumstances and the underside of mass culture that certain genius collaborators on the production side of it were kind and clever enough to share with us. For some of my generation, this probably began in earnest with Bullwinkle and Rocky, the flying squirrel (I’m giggling just writing those words), but there were little tastes of it everywhere from fashion, news and science magazines (and MAD Magazine, of course), to Hollywood spectacles, to advertising and television commercials. (Hell, even politics: consider the Kefauver hearings or Nixon’s infamous “Checkers” speech, or Krushchev banging his shoe on his U.N. desk.)

Jorge Gutierrez actually grew up on the U.S.-Mexico border, living with his family in Tijuana, but attending school in San Diego, and picking up and unpacking the cultural baggage both coming and going. One can imagine the stresses entailed by that constant cross-border commute; but through it all, Gutierrez kept his eyes wide open and imagination running at full-tilt. He was becoming a bricoleur of pop cultural iconography probably before he even knew he wanted to become an artist. But it’s a phenomenon that almost anyone who grew up in the late 20th century or later can appreciate because we all grew up in a kind of pop culture bricolage fashioned out of our variable circumstances and the underside of mass culture that certain genius collaborators on the production side of it were kind and clever enough to share with us. For some of my generation, this probably began in earnest with Bullwinkle and Rocky, the flying squirrel (I’m giggling just writing those words), but there were little tastes of it everywhere from fashion, news and science magazines (and MAD Magazine, of course), to Hollywood spectacles, to advertising and television commercials. (Hell, even politics: consider the Kefauver hearings or Nixon’s infamous “Checkers” speech, or Krushchev banging his shoe on his U.N. desk.)

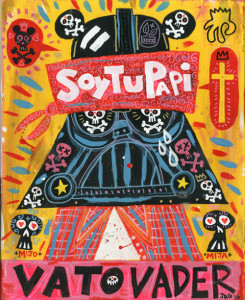

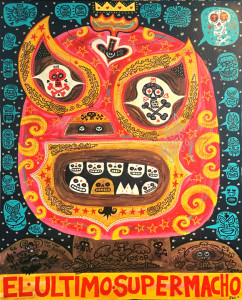

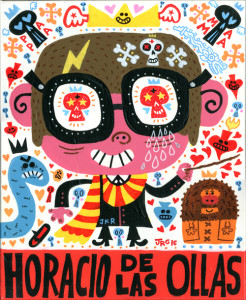

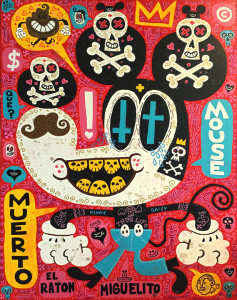

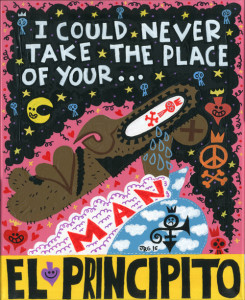

Gutierrez’s “First Solo Art Show” (which may be a slight exaggeration considering his award-winning career in animation), Border Bang, practically lights up the Escalante Gallery with its neon color and graphic electricity. Gutierrez’s concentration at CalArts was animation, but his mastery of a high-impact tapestried species of graphic, a kind of superflat collage iconography is striking. There are so many cross-cultural (as well as direct artistic) influences and elements at play here, it’s hard to sort them all out. (We see an iconizing aspect of Jean-Michel Basquiat, with something like Keith Haring’s electric action-line accents.) All of it is distilled through the filter of Mexican folk culture, ‘luchadorismo’ and magic – a conflation of Dia de Los Muertos with el Dia de Los Niños. (Consider his play on Harry Potter, “Horacio de las Ollas” – or as the painting is actually titled, “La del Niñito Brujo.”) The eyes are always some permutation of skulls or jolly roger skull-and-crossbones, sometimes framed by paisley masks or specs; nostrils flare or turn-up in porcine fashion (or occasionally fashioned out of playing card symbols – hearts and spades); hair spikes and squiggles away or is flattened out in little helmets of hair beneath actual hats, helmets or (of course!) sombreros. Hands are those strangely familiar four-fingered mutations that are the exclusive province of animated cartoons from, well, that day that once belonged to Rocky and Bullwinkle.

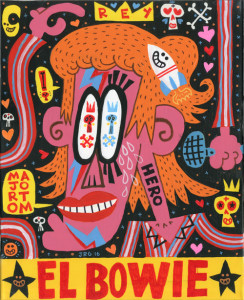

It’s a very emo world. Gutierrez is pouring his heart out here – in vivid color. The icons (the famous and infamous: from Bowie to Frida Kahlo, to Senor T, to the Hulk; from Jules/Samuel L. Jackson (of the jeri-curls) from Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction to Bruce Lee; Magic Johnson, Darth Vader, Mickey Mouse (here rendered as “Super Muerto Mouse”), SpongeBob, El Chapo; from (going back to the innocent 1950s) Cantinflas to that Diablo himself, Donald Trump) swim in seas of hearts as well as slightly kawaii skulls; their eyes stream tears. (On a certain level, one wants to ask: are these also in a sense death or devotional images for mourning?) Pinks, reds and neon blues and yellows make the superflat icons nevertheless throb with life (or perhaps a reflection of our stubborn devotion).

The cultural scavenging and souvenir collecting that Gutierrez began during his childhood of border-crossings continues in this merzgrafik mash-up of bits and pieces of everything from commercial packaging (I think of Japanese toy and ramen packaging), to Japanese kawaii toy aesthetics (but very distinct from Murakami’s airbrushed and manicured renditions) to American music and movies and their advertising and merchandising, to animated entertainment both Japanese and American (including possibly Jay Ward himself). But everything and everyone is made over into something that belongs to a universe exclusively of Gutierrez’s imagination. They’re heroes transformed – ready for an entirely new narrative. (E.g., Bowie – here, actually a ‘Major Tom’ that belongs to Gutierrez’s own story; or a Super Muerto Mouse that really has nothing to do with Disney’s creation.) There’s a continuity here with Gutierrez’s work as an animator – there’s the stuff of a hundred separate feature films or animated stories here.

We all grow up on borders of one sort of another, criss-crossing them; importing from one side what we don’t have on the other, appropriating it to push ourselves over to the other side (which is always greener or at least fascinating in one way or another); hybridizing what we find on either side; translating our sensibilities from alien to approachable, or even appreciated.

We reinvent the cultural narrative as we reinvent our characters; it’s the way aspiration and fantasy figure in building our cross-border society – and Gutierrez gets all of this – convulsively, gorgeously.

The fascination with Morrissey, The Smiths; and a few other English alt-rock bands of the 1980s, 1990s and beyond has been a subcultural phenomenon here in L.A. and through a good part of Mexico, especially Mexico City, for at least a decade. (It’s as if the Elvis/El-Vez pompadour cross-faded without a beat into the Morrissey quiff.) I always wonder where it began and what it means. I’ve been a fan of the Smiths and Morrissey solo for – it feels like forever (but I’m guessing only goes back to 1985 or 1986). It seemed as by the time I was really getting addicted, they were already breaking up. But although Johnny Marr’s fantastic guitar style was missed (and still is), Morrissey was always undeniably their heart and soul. I can’t help thinking of that line from one of their songs: “That joke isn’t funny anymore. It’s too close to home and too near to the bone.” Why wouldn’t they get it before the rest of us? The alienation (and inequality) – which persists dramatically; the emotion behind it all worn directly on the turned-inside-out-sleeve; it’s ASCO-in-the-disco – an ‘elite of the obscure’ channeled into a cumbia two-step. Why bloody not? I sometimes wonder if the geniuses behind Night Gallery were subconsciously responding to this throbbing call when they first ventured down to Lincoln Heights.

Although I consider myself an Eastsider in Los Angeles, I confess the art world has drawn me to the east side somewhat more than the call of an alt-Latin Brit-pop vibe; but I have not been deaf to its siren call. Was I just waiting for a more Mexican Morrissey all along? I still love and listen to Morrissey, but for the last year or so, nothing has started my heart quite the way Mexrrissey has. There are tribute bands and then there is Mexrrissey. Mexrrissey’s musicians are mostly Mexican and from Mexico City, but more important is that this is an ensemble of stars. Even listening to the original songs, you have a sense of how Marr’s guitar lines or the rhythm leads might be easily adapted to Latin rhythms; but putting it altogether in a thoroughly Latin package and taking it to this level is another feat entirely. I’ve been a fan of Chetes for some time already; but here he’s in the center of a master-ensemble led by two genius composer-musicians: Camilo Lara and Sergio Mendoza (of Calexico). Also on hand are Alejandro Flores (Café Tacuba), Jay de la Cueva, and Jacob Valenzuela. Do I need to go on? Actually I will: it’s not just guys. Ceci Bastida is a terrific singer; and “The Last of the Famous International Playboys” has now been reset as “International Playgirl.” Her renditions of “Cada Día Es Domingo” (“Every Day Is Like Sunday”) and “International Playgirl” are now my go-to renditions of those two Morrissey hits. Alex Gonzalez is their fantastic trumpeter. (I’m probably missing someone, but I honestly don’t remember.)

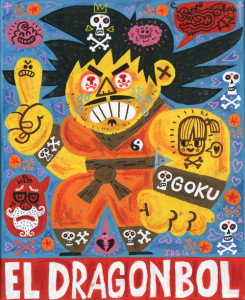

This is tribute in the best, largest sense. The Mexrrissey ensemble magnifies Morrissey’s flat-line alienation and sardonic detachment into a full-throated emotional expression. Just for one example, the already anthemic “Every Day Is Like Sunday,” underscored by insistent mariachi rhythms and lit in the upper register by its brass emphasis becomes a sprawling river of regret and mournfulness that can carry you from Mexico to Manchester and back again. I still haven’t quite connected the notes that take us from Mexican cumbia and emo-rock to Morrissey’s sui generis deadpan mix of sincerity and irony to achieve something with an Atlantic-spanning tsunami power and musical/emotional clarity; but it’s a joy to listen and dance to. Gutierrez comments on the phenomenon in his (on-line) commentary to one of his paintings, Goku Tu Madre. “Mexicans LOVE Dragonball. Like with Morrissey, it can’t truly be explained.” But as long as we can dance to it, we don’t really need to. Estuvo bien.

This is tribute in the best, largest sense. The Mexrrissey ensemble magnifies Morrissey’s flat-line alienation and sardonic detachment into a full-throated emotional expression. Just for one example, the already anthemic “Every Day Is Like Sunday,” underscored by insistent mariachi rhythms and lit in the upper register by its brass emphasis becomes a sprawling river of regret and mournfulness that can carry you from Mexico to Manchester and back again. I still haven’t quite connected the notes that take us from Mexican cumbia and emo-rock to Morrissey’s sui generis deadpan mix of sincerity and irony to achieve something with an Atlantic-spanning tsunami power and musical/emotional clarity; but it’s a joy to listen and dance to. Gutierrez comments on the phenomenon in his (on-line) commentary to one of his paintings, Goku Tu Madre. “Mexicans LOVE Dragonball. Like with Morrissey, it can’t truly be explained.” But as long as we can dance to it, we don’t really need to. Estuvo bien.