Every morning I wake up and see At Home with the Nortes (1990). In this black-and-white photograph, a family sits in the living room watching television. This could be construed as a typical family activity, but the family is hardly typical in Laura Aguilar’s depiction. Each face of its four members—two young boys, father and mother—is made up in the style of the Mexican Dia de los Muertos. The brothers seated on the rug playing with dinosaurs gaze at the television screen, on which a wide-eyed Looney Tunes character stares back in disbelief from behind bars toward the couch where the parents sit, eyes glued to the screen.

At Home with the Nortes, 1990, gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches, courtesy of the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. Artwork © Laura Aguilar

Like much of Aguilar’s work, everything in this scene lines up perfectly. She photographs it as if nothing is out of the ordinary. What is remarkable about Aguilar’s approach to photography is that she takes things as they are and documents what is in front of the camera—including her own large naked body—without passing judgment, asserting the value of difference. Collectively, her works have power and integrity, yet more importantly—and what sets her apart—is her openness and sense of play. While the works can be quantified and discussed in terms of a feminist, Latina or lesbian agenda, Aguilar is not a theoretical artist, she is an explorer and an aesthete who uses the specificities of her body and her life as raw material.

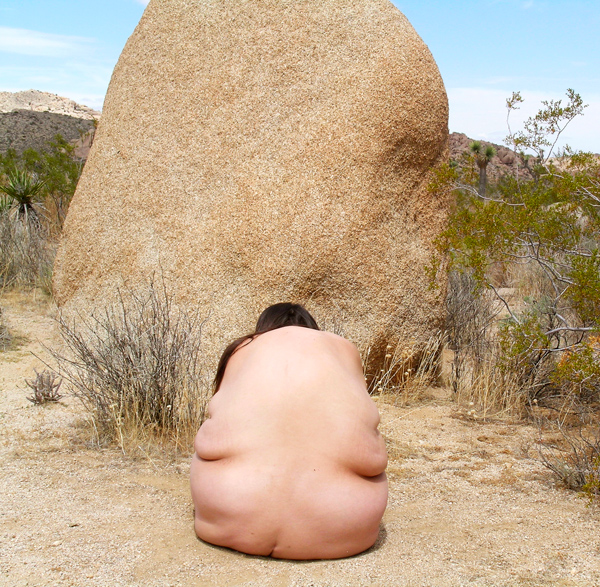

Grounded #111, 2006/2016, inkjet print

Aguilar’s first retrospective in Los Angeles, “Laura Aguilar, Show and Tell,” appears at the Vincent Price Art Museum and includes photographs and videos from 1976 to 2007. This exhibition, curated by Sybil Venegas, is part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative which aims to explore relationships between Latin-American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles.

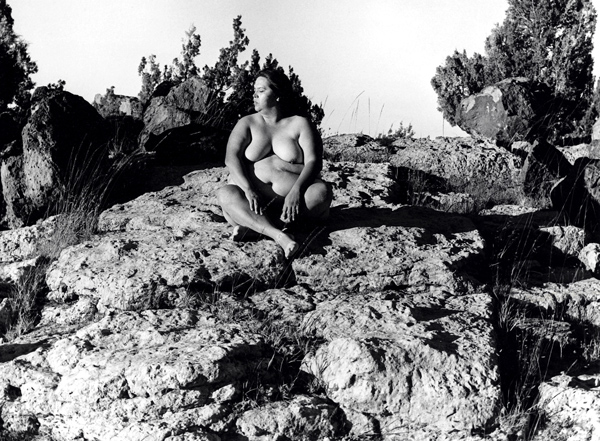

Laura Aguilar, Nature Self-Portrait #11, 1996, Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches

Aguilar, 59, is presently having health issues and was unable to sit for an interview, but she answered a few email questions. In regards to her work being celebrated now with a retrospective, she responds, “I have been celebrated before and it was nice. But now, I feel different because I have been trying to survive to get my work shown and it’s been a struggle. So it’s hard to think about my work being celebrated because I have been so focused on staying alive.”

Aguilar is pleased her work is being seen in this context, as she “always did [her] own thing and tried to get [her] name out there.” Yet she also acknowledges that her struggles with health issues over the years have limited her abilities to make and show her work.

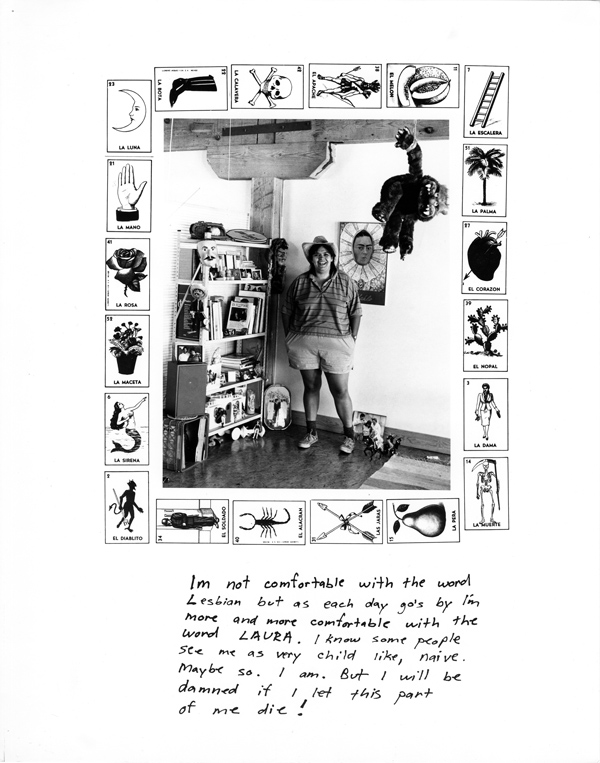

Laura from “Latina Lesbians” series, 1988, gelatin silver print

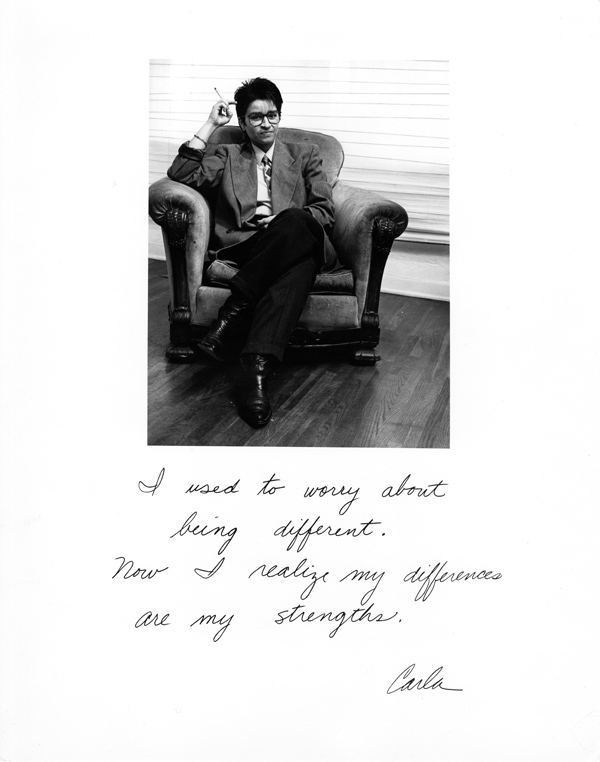

Aguilar began photographing in the late 1970s and by the mid-’80s had developed connections with LA’s Chicano art scene where she met other like-minded artists who later became subjects of her early portraits. Though Aguilar began her career making photographs of her environment and friends, she is renowned for her self-portraits. As Aguilar began to identify with the Latina and later the LGBT communities and came to terms with her physical self, notions of race, body and sexuality became central to her work.

On the prints in her “How Mexican is Mexican and Latina Lesbian” series are handwritten texts by her sitters. This early image/text juxtaposition allowed their words as well as their images to tell a story. Identity politics were the rage in the 1990s and Aguilar’s works investigated both personal and global topics; she was never abashed in making herself vulnerable—for her, the personal was political. In the late 1990s, Aguilar began to photograph herself in the natural landscape, creating black-and-white photographs that featured her body in relation to the shapes and textures of the rocks and trees around her. In 2006 and 2007, she created intimate color photographs in which the cracks of her body and tones of her skin were seen in relation to the formations of layered rocks like those found in the Joshua Tree desert region.

Motion #56, 1999, gelatin silver print; all images courtesy of the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, artwork ©Laura Aguilar.

Aguilar has an acute awareness of the pros and cons of her body and while her confessional videos lament what it is like to be so overweight, the photographs also celebrate the beauty of her body as being a part of nature itself. There is no doubt that it takes courage to expose one’s self and to share that vulnerability, but it can also be empowering. Aguilar’s work suggests there is no reason to be ashamed. She delights in the fact that she can play and it is this playfulness that shines in everything she does, be it her “Toy” series (2006), the most recent work in the exhibition (which includes an image of a scantily clad, shield-holding, blue-haired femme fatale toy) or images from “Stillness” (1999) where Aguilar is hyper-aware of how the folds of her naked body meld with vast and open landscapes. Aguilar is an astute and driven artist who looks both inward and outward with a sensitive and compassionate eye toward all that surrounds her.

Images courtesy of the artist.

“Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell,” at Vincent Price Museum at East Los Angeles College; runs through February 10, 2018.