Years before the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” was initiated, the Museum of Latin American Art was exploring Latin and Latino culture. Its previous 2011–12 PST, “Mex/L.A. ‘Mexican’ Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930–1985,” explored the relationship between artists and supporters on both sides of the border, and included murals by José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Yet in the current PST initiative, MOLAA is reaching beyond what is commonly considered Latin or Latino art with its museum-wide “Relational Undercurrents” exhibition. Covering the Caribbean islands, the show displays work from non-Hispanic islands, including Aruba, The Bahamas, Barbados, Guadeloupe, Haiti and St. Martin, in addition to Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Curated by Tatiana Flores, a Rutgers University professor of Latino and Caribbean Studies, and Art History, the exhibition addresses the so-called boundaries separating Caribbean countries and territories, and then artistically, historically and conceptually connects these entities through nearly 200 art pieces.

The show explores the work of more than 80 artists residing in these islands in today’s post-colonial era, while revealing their frustrations and desires. With many artists drawing on a common legacy of colonialism, issues of history, identity, migration, race and ethnicity pervade their paintings, installations, sculpture, photography and videos. Their work ultimately expresses the underside of Caribbean life—a world that is light years away from the advertised version of the islands as a tropical paradise.

Scherezade Garcia, In My Floating World, Landscape of Paradise from the series Theories on Freedom, 2011, courtesy of the artist and the Lyle O. Reitzel Gallery, New York.

One of the most powerful pieces in the show greets the viewer in the museum lobby. Scherezade Garcia’s In My Floating World, Landscape of Paradise (2011) consists of numerous large, blue plastic lifesavers, bound together with plastic ties, each with a JFK luggage tag. Expressing the desire for freedom through any means—by boat, plane or lifesavers—this installation epitomizes the exhibition’s recurrent theme of yearning for a better and different world.

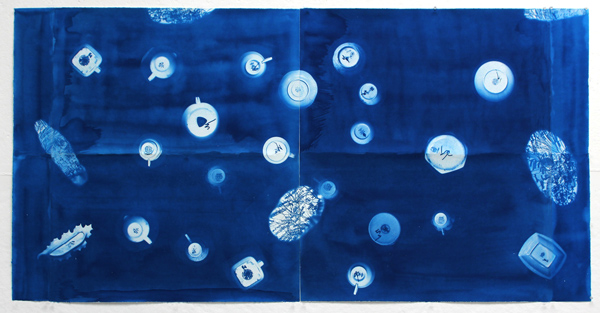

Juana Valdes, Under View of the World / El Mundo desde abajo, 2015, Courtesy of the artist.

“Relational Undercurrents” is divided into four thematic sections. The “Conceptual Mappings” section includes maps and globes that re-imagine the world. Juana Valdes’ Under View of the World (2015), a cyanotype print with a deep blue background, appearing like the sea, features superimposed objects including gems, bottles and trinkets, appearing like islands. It evokes colonialism’s dependence on trade at the expense of the islanders. Firelei Báez’ gouache, ink and chine-collé on de-accessioned book pages anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River (2014–15), with female body parts superimposed over 19th-century maps, suggests the female islanders’ objectification by the traveling male patriarchy. In Ewan Atkinson’s Starman photos on light boxes (2009), the ephemeral superhero dominates urban scenes, implying the desire of the artist to overtake the environment.

The work in the “Perpetual Horizons” section focuses on the horizon, a constant presence in the islands, reminding residents of the borders that have kept them colonized and/or entrapped. Marianela Orozco’s digital print Horizons (2012) features a stretched out naked female as the horizon line, with a background of clear blue sky and puffy clouds. Yet its dreamy depiction of a female belies the deeper issue of degradation of women on the islands. Yoan Capote’s Island (The Night) (2011–12), a recreation of the ocean meeting the sky made out of fishhooks on jute on panel, is a poignant reminder of the islanders’ omnipresent relationship to the sea.

Tony Capellán, Mar invadido, 2015, found objects from the Caribbean Sea, courtesy of the artist.

“Landscape Ecologies” address the environment as a place of shared ecosystems and habitats, referencing history, ecological challenges, and even disease and degeneration. One of the most alarming pieces in this section and in the exhibition is Tony Capellán’s Found objects from the Caribbean Sea (2015). This roomful of plastic cast-offs retrieved from the sea, including broken toilet seats, baskets, toys and waste from the medical industry, is organized by colors on the floor, from white to light blue to green to dark blue to black. The artistic arrangement of the detritus further emphasizes our besmirching of the environment, particularly in places bordered by the sea.

“Representational Acts” features work with political viewpoints in relation to race, gender, colonialism and more. David Bade’s My Name is Europe, Hi Europe (2014) is a large, colorful semi-abstract painting, depicting a jumble of characters; it conveys the foreboding that pervades much of this exhibition.

Antonia Wright, Suddenly We Jumped, 2014, photo by Rudy Duboue, courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Antonia Wright’s Suddenly We Jumped (2014), a slow-motion video of the artist smashing her nude body through a sheet of glass, evokes the Futurists’ fearless “mortal leap”—her title quotes Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who penned the Futurist Manifesto. Here, that leap seems expressive of a fervent determination to break through the subjugation of race, sex, nationalism and a centuries-old legacy of oppression. Jumped, then, viscerally embodies the mood of many of the works exhibited in “Relational Undercurrents.”