Your cart is currently empty!

Conspiracy & Otherworldliness

Last Saturday night, we hopped over to the opening reception at Nicodim Gallery featuring works of Mi Kafchin in her thought-provoking show, “Chemtrails.” Walking into the gallery, I knew little about the artist or the concepts behind her practice. My only peek into her world came from an enticing video posted on Instagram earlier in the week by curator Aaron Moulton. The video featured footage of Kafchin beginning a sketch on a massive blank 9’x50’ piece of paper with ease and confidence. As if channeling the marks from some otherworldly concept, Kafchin initiated the drawing without reference, but rather from the depths of her internal musings. In the video, Kafchin noted she started the illustration with “the artists’ workbench,” as this is where all creation starts. As she continued to draw, manifesting her realities with each mark, she proved just that. The video snippet was enough to initiate intrigue, so we set out to see the work in person.

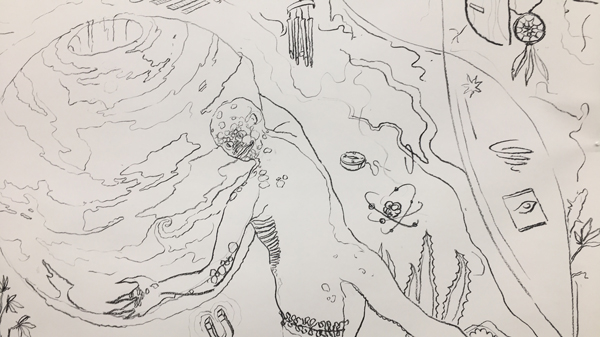

Upon entrance, we were met by the sprawling monumental drawing featured in the video. Inundating us with a plethora of symbolic imagery, the piece was loaded with personal and universal narrative. Little did we know, this was just the tip of the iceberg.

The drawing was accompanied by equally striking and vibrant large-scale paintings as well as sculptural work. Stationed in front of the drawing was a sculpture featuring the bust of conspiracy theorist, and inspiration for much of Kafchin’s concepts, David Icke. Icke’s worldview of New Age conspiracy was a constant theme present in the exhibition.

Approaching the drawing, we attempted to digest the complex monument before us. Luckily our attempts were intercepted as Moulton generously offered to guide us through the intricate web of Kafchin’s creation. We began at one side of the large drawing and moving from left to right, Moulton walked us through the visual timeline, which depicted a Holocaust of the future of sorts. The imagery escalated from the artists’ bench rather abruptly, weaving in and out of esoteric allusions to grand, universal narratives. Kafchin’s drawing really seemed to cover it all; from conspiracy theories involving of 4g vs. 5g vibrational energy, extraterrestrials, an inter-dimensional race of reptilian beings, to flat earth theories and even fluoride in toothpaste. I could hardly keep us as we ventured through the trajectories of Kafchis’ brilliantly articulated visual worlds. She ends the work with a masked figure in the far right-hand side of the drawing, whose omnipotent power remains vague.

Although much of the pieces depicted landscapes and characters seemingly otherworldly, Moulton revealed Kafchin’s imagery was rooted in a deeper, more personal response to the fact that she was born only a few months after the Chernobyl Disaster in 1986.

In “Chemtrails,” Kafchin visually represents her incessant internal escapades, which attempt to process how radioactive toxins from Chernobyl and other infiltrating forces altered her body and mind. Kafchin boldly evokes surreal and not popularly acknowledged concepts. Her work illuminates the frightening realization that in the grand scheme of things, we have little agency in controlling that which we don’t fully know—and as Kafchin illustrates, it’s quite a lot.