There is still a sense of shock over racially charged policies out of Washington that feel out of line with the West Coast’s progressive ethos. Los Angeles’ major art institutions are trying to counteract this as best they can by presenting more exhibitions by people of color (POC), increasing representation and amplifying voices once silenced in historically white spaces. In the past year, Angelenos have seen many important museum exhibitions by POC artists, tipping the scales toward an equilibrium that is long overdue.

The Broad presented Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983, which celebrated the vital contributions of black artists during two revolutionary decades in American history, beginning at the height of the Civil Rights movement. “Any fault lines we see in contemporary culture are plainly visible in this exhibition,” said Broad founding director Joanne Heyler at the press preview. Soul of a Nation features such important artists as Romare Bearden, Alma Thomas and Noah Purifoy, who created opportunities when recognition was scarce owing to inadequate acknowledgement from the predominantly white art world. The exhibition rewrites American art history with keenly sharp hindsight and it is perhaps worth mentioning that it was organized by London’s Tate Modern.

Installation view of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 at The Broad, 2019. Photo by Pablo Enriquez.

The Skirball Cultural Center hosted Black is Beautiful by influential photographer Kwame Braithwaite, who helped coin the iconic slogan through his portraits of black musicians, organizers, and fashionistas in the ’50s and ’60s. “Black is Beautiful” fueled a Civil Rights movement and inspired African Americans to love themselves even when the world told them not to. “So many issues we faced in the 1960s, we face again today,” said curator Bethany Montagano at the press preview. The exhibition offered Angelenos the chance to address and possibly overcome the divisive challenges of this American moment ripe with racial tension.

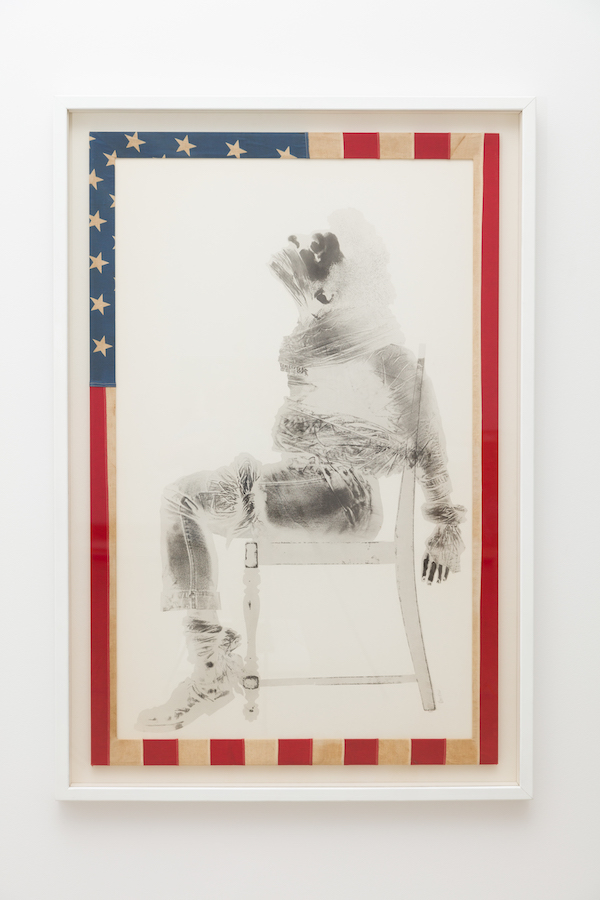

David Hammons, “Injustice Case,” 1971. On view in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 at The Broad, 2019. Photo by Pablo Enriquez.

This Fall, LACMA’s groundbreaking gallery at Charles White Elementary School—the former Otis campus in MacArthur Park where Charles White was once its first African-American faculty member—presents Life Model: Charles White and His Students. The state-of-the-art gallery benefits the school’s new magnet center for visual arts, with public access restricted to three hours on Saturdays. “The early position of my father was that education isn’t privileged,” said Ian White. “Privileged” is not a word often used to describe the student body at this historically very low-performing school, where the hope is that access to the gallery, the new arts curriculum and the legacy of Charles White will connect the dots for what art can do for education. With plans for the museum-grade gallery to become an extended classroom for a whole school of low-income Hispanic students, White’s insistence that art is for everyone continues to drive societal progress for disenfranchised communities.

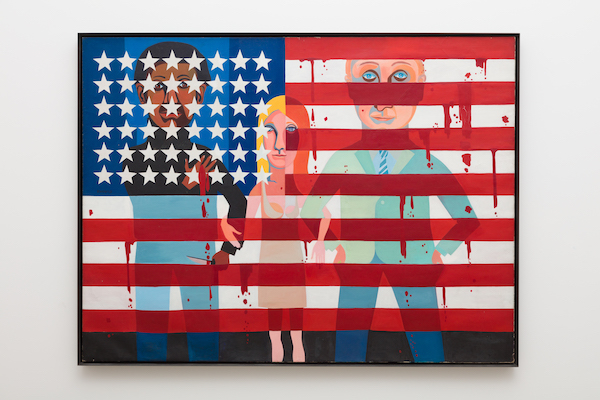

John Riddle, “Untitled,” 1970s.

Craft Contemporary’s exhibition of sculptures and assemblages by John T. Riddle Jr. and his contemporaries highlights the work of a largely underappreciated group of black artists in LA. “Younger generations of black makers in LA stand on the history, tradition and shoulders of this group,” said curator jillith moniz in an interview. Founder of Quotidian gallery in Downtown LA and former lead curator at California African American Museum, moniz is notably the only black female curator of any of the shows mentioned in this article. She continues to tirelessly present work by the community of black artists who made LA a unique and important space for people who come to be creators and use materials in an innovative way.

LACMA’s upcoming exhibition of renowned 92-year-old black sculptor Betye Saar, a living legend in no small part due to her socially critical work. LACMA’s show will look at the relationship between Saar’s preliminary sketches and their final realization as found-object assemblages.

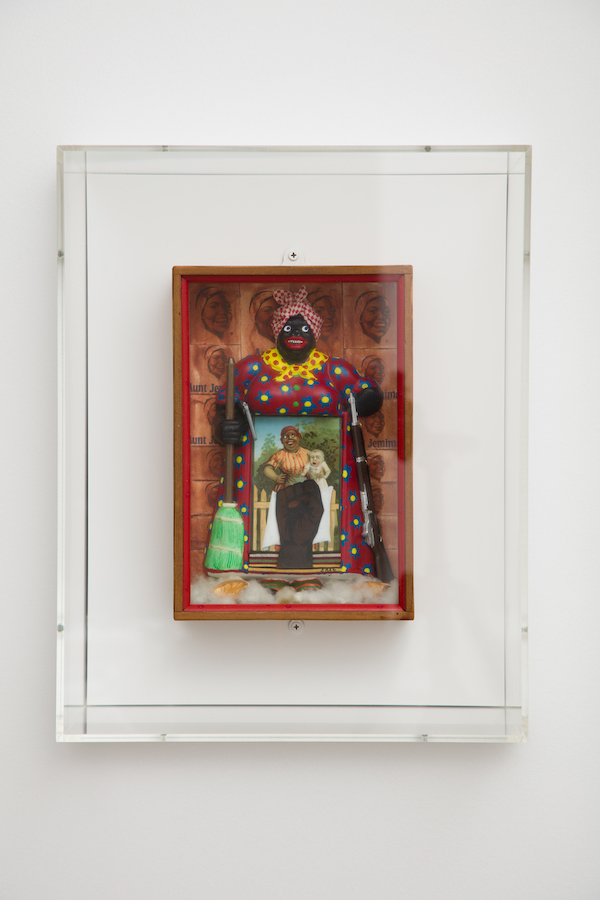

Betye Saar, “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” 1972. On view in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 at The Broad, 2019. Photo by Pablo Enriquez.

I’ve concentrated on shows featuring black artists because as a Mexican, I did note an absence of Latinx artists in the round. With Latinx communities continuing to experience reprehensible treatment by the current administration, a slew of exhibitions presenting work by Hispanic artists who represent the majority population in LA should be the next trend to sweep the city. After all, art may be the only place a person can be seen whole—where tribulations are not discredited but magnified. Art exhibitions that normalize the “other” may be the best agent for change yet.

0 Comments